Cell gangs may help cancer spread

Mouse experiments show that groups of cancer cells can boost the chance that a new spinoff tumor will develop

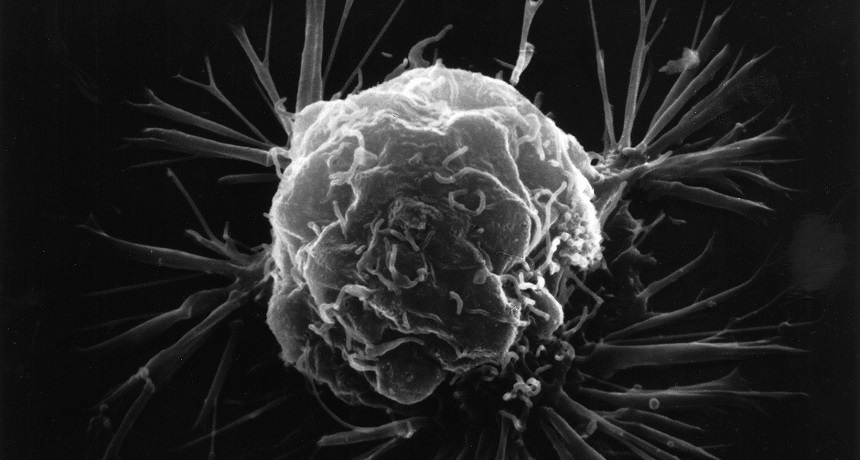

Experiments in mice showed that breast cancer cells spreading in groups are 100 times as successful in forming a new tumor as will be a single, fleeing breast cancer cell (shown).

Bruce Wetzel and Harry Schaefer / National Cancer Institute

Most people who die from cancer succumb only after the disease spreads. Recent experiments with mice may help researchers better understand why. In those experiments, biologists found that some cancer cells left a breast tumor as a group. They traveled together, eventually forming a new tumor elsewhere. These traveling gangs of cells were 100 times more likely to form a new tumor than were lone cancer cells, the new study showed.

Understanding how cancer spreads can lead to the development of better treatments, explains Crislyn D’Souza-Schorey. This cell biologist at the University of Notre Dame, in Indiana, did not work on the new study. The take-home message, she told Science News, is that drugs designed to kill individual cancer cells may not work all that well against roving gangs of these cells.

Biologist Kevin Cheung of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md., reported his team’s new findings in Philadelphia on December 7 at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology.

His group began by changing genes in mice. Found in DNA, genes hold the information that instructs every cell on how to grow and function. When genes go haywire, they may cause a disease such as cancer. Cheung’s crew tweaked the genes in mice so that breast cancer cells that grew in the animals’ bodies glowed. Some glowed red. Others glowed green.

The cancer cells’ glow allowed Cheung’s team to track their movement. Under a microscope, the scientists watched cells leave a tumor. Roughly one-third of the cells that departed left the parent tumor in clumps. During some trials, gang departures were even higher: They could account for more than 60 percent of all cells that left.

In another experiment, the researchers injected cancer cells into the tails of mice. When cells were injected as a clump, they were 100 times more likely to form new tumors than were cells that had been injected individually.

Cheung says that when cells work together, they appear to support one another. The results might lead researchers to shift away from treating “the Superman cell” and turn instead to targeting the gangs, he told Science News.

D’Souza-Schorey finds these new data compelling. Still, she told Science News, no one knows yet if other types of cancer also migrate in clumps — or if the findings will be useful in treating people.

Power Words

biology The study of living things. The scientists who study them are known as biologists.

cancer Any of more than 100 different diseases, each characterized by the rapid, uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells. The development and growth of cancers, also known as malignancies, can lead to tumors, pain and death.

cell The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism. Typically too small to see with the naked eye, it consists of watery fluid surrounded by a membrane or wall. Animals are made of anywhere from thousands to trillions of cells, depending on their size.

gene (adj. genetic) A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

succumb To die or to give up and surrender to some overwhelming force.

tumor A mass of cells characterized by atypical and often uncontrolled growth. Benign tumors will not spread; they just grow and cause problems if they press against or tighten around healthy tissue. Malignant tumors will ultimately shed cells that can seed the body with new tumors. Malignant tumors are also known as cancers.