Chigger ‘bites’ may trigger an allergy to red meat

The tiny, red, spider-like parasites can provoke rare food allergies in some people

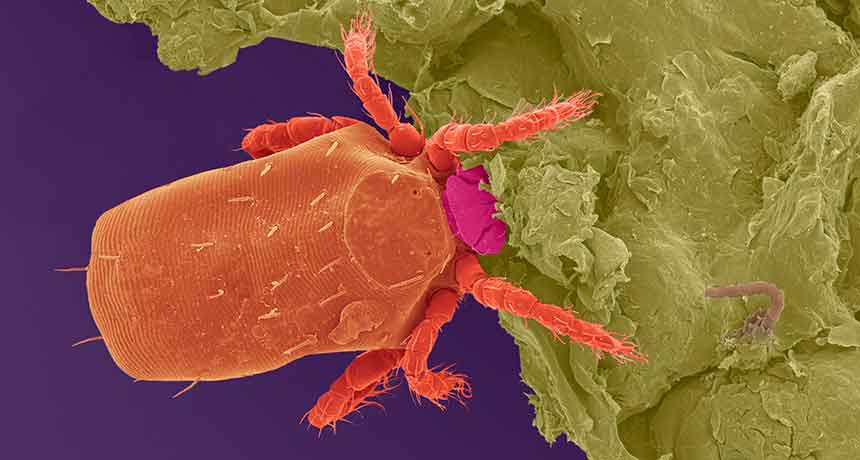

This magnified image shows a chigger feeding on human skin. New data find that some people appear to develop meat allergies after these little parasites attach to their skin and begin eating it.

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy/Science Source

Chiggers are a common summertime irritation. These tiny parasites — a type of mite — can leave itchy, red spots on the skin. And that itch can be so severe that it drives people to distraction. But a new report suggests these mite bites might trigger even bigger problems: an allergy to red meat.

Chiggers are the larvae of harvest mites. These tiny spider relatives hang out in forests, shrubs and grassy areas. Adult mites feed on plants. But their larvae eat skin. When people or other animals spend time in — or even just walk through — areas with chiggers, the larvae may drop or climb onto them.

Once the larval mites find a patch of skin, they inject saliva into it. Enzymes in that saliva help break down skin cells into a gloopy liquid. Think of it as a smoothie that chiggers slurp up. It’s the body’s reaction to those enzymes that make the skin itch.

But the saliva may contain more than just enzymes, finds Russell Traister. He works at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, N.C. As an immunologist, he studies how our bodies respond to germs and other invaders. Traister teamed up with colleagues at Wake Forest and the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. They also worked with an entomologist, or insect biologist, at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. The group reported on three cases of people who developed allergies to red meat after a skin infestation of chiggers. Such allergies had previously been seen only after tick bites.

The body detects an invader

How could a chigger’s dining on skin make the body later react to eating meat? Red meat comes from mammals. And the muscle cells of mammals contain a carbohydrate made from small sugar molecules known as galactose (Guh-LAK-tose). Scientists call this muscle carb “alpha-gal” for short.

Meat is rich in muscle. Normally, when people eat red meat, its alpha-gal stays in their gut, where it causes no problem. But some critters, such as the Lone Star tick, have alpha-gal in their saliva. When these ticks bite someone, that alpha-gal gets into their blood. The victim’s immune system can react as though alpha-gal is some germ or other invader. Their body then creates lots of antibodies against alpha-gal. (Antibodies are proteins that help the immune system respond quickly to what the body views as a threat.)

The next time these people eat red meat, their bodies are primed to react — even though that alpha-gal poses no real harm. Such immune responses to non-threatening things (like pollen or alpha-gal) are known as allergies. Symptoms may include hives (big, red welts), vomiting, a runny nose or sneezing. Affected people may even go into anaphylaxis (AN-uh-fuh-LAK-sis). This is an extreme allergic reaction. It makes the body go into shock. In some instances, it can cause death.

Allergic reactions to alpha-gal are tricky to identify. They only show up several hours after eating meat. So it can be hard for people to realize the meat was responsible.

Hunting down the cause

Traister and his team knew tick bites could trigger alpha-gal allergies. It’s not very common, but does happen. So when they met three patients who had recently developed the allergy, it wasn’t too surprising. Except that none had recent tick bites. What each patient did have in common: chiggers.

One man became allergic after his skin had become infested by hundreds of chiggers while hiking. He had been bitten by ticks years earlier. But his meat allergy only showed up after the chigger encounter — soon after.

Another man had worked near some shrubs. He found dozens of tiny red mites on himself. His skin also developed the telltale red blotches from some 50 chigger bites. A few weeks later, he ate meat and for the first time ever reacted by breaking out in hives.

And a woman similarly became allergic to meat after chigger bites. Although she too had suffered tick bites years earlier, her meat reaction emerged only after the chiggers.

Traister’s group described these cases July 24 in The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

Could this be mistaken identity?

It might seem these chigger encounters were clearly behind the new cases of alpha-gal allergy. But Traister cautions that it can be hard to know for sure. Chiggers look a lot like “seed ticks” — the tiny larvae of ticks. The skin reaction to each also looks similar and becomes equally itchy.

For these reasons, Traister says, “It is easy for a layperson to misidentify [what] has bitten them.” And that, he adds, makes it difficult to prove chiggers caused the meat allergy. Still, the circumstances certainly suggest the three new cases got their meat allergy from chiggers. Two of them even described their attackers as red — the color of adult mites. The researchers also questioned several hundred other people with alpha-gal allergy. Some of them, too, said they never had been bitten by a tick.

“The notion of chiggers causing red-meat allergy makes sense,” says Scott Commins. He is an immunologist at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. He was not involved with the study but notes that chiggers and ticks share some habits. “Both can take blood meals through the skin,” he says, “which is the ideal route to create an allergic response.”

The researchers are working to figure out whether chiggers are the source of some alpha-gal allergies. Fortunately, it’s not something to get too worried about. “Overall, this allergy is very rare,” Traister says. Few people infested by ticks or chiggers ever become allergic to meat.