Cleaner water helps male fish again look and act like guys

Cutting pollution could keep some male fish from becoming feminine

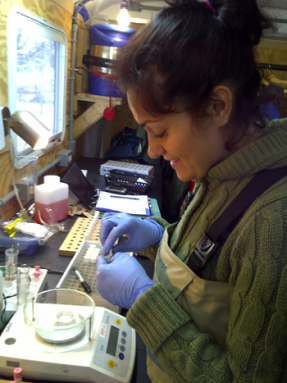

Researchers caught this male rainbow darter fish in the Grand River after improvements to a water treatment plant upstream. This fish now sports its normal rainbow colors.

Courtesy of Mark Servos

Some types of water pollution can make male fish look and act like females. But a new study shows that better water treatment can prevent that. And that could allow fish populations to thrive.

Water treatment plants are supposed to clean the water from our toilets, showers and sinks before releasing it into rivers, lakes and oceans. They are also supposed to treat water from manufacturing plants. But these water-cleanup plants were never designed to remove all pollutants. Most were built before anyone realized that hormones and hormone-like chemicals could show up in the water. And such chemicals can prove a big problem for fish.

How? They can fake out cells of a male’s body by sending signals telling those cells that this he fish is actually a she. These feminized guy fish may then have little interest in fertilizing a female’s eggs — or he may do so poorly. The result: Fewer baby fish. Or at least that’s the risk.

Male feminization of fish has been showing up in rivers throughout North America.

Mark Servos and his team have been monitoring it in Canada’s Grand River. Servos is an aquatic toxicologist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario. There, he studies the effects of water pollution on rainbow darter fish.

At least once a year from 2007 to 2012, his team caught and examined rainbow darters at a site downstream of a water treatment plant. And depending on the year, between 80 and 100 percent of the males had eggs in them. Egg-making is something that only female fish should do. Moreover, those eggs were in the males’ testes — reproductive organs that normally make sperm (cells used to fertilize a female’s eggs).

Many affected males didn’t even look right on the outside. “Male rainbow darter fish are really colorful,” Servos says. Or at least they should be. “This color is important for attracting mates.” Yet some local males were becoming drab. That could make it hard for them to find a mate.

Clearly, something was very wrong in these male fish. Until 2013, that is. Suddenly, the number of feminized male fish started to fall. This happened at the same time that the local treatment plant changed how it cleaned the water.

The team’s data now link these two observations in a paper published early online in Environmental Science and Technology.

The problem with feminized males

The bodies of animals — including humans — use hormones to tell their cells when to switch various activities on or off. Those hormones fit like keys into “locks” on the outside of a cell. Scientists call these locks receptors. When hormones connect with their locks, they affect how an animal will develop and act. But certain pollutants act like fake keys. These hormone mimics are known as endocrine (EN-doe-krin) disruptors. They can turn on or off some normal function of an animals’ cells — but at the wrong time. That can make an animal develop or act in a way that isn’t natural.

From 2007 to 2012, Servos’ team found high levels of endocrine disruptors in the water downstream of the water treatment plant. Many of these chemicals mimicked the action of estrogen, a female sex hormone. Some endocrine disruptors came from birth control pills. Their synthetic hormones left a woman’s body in urine. Flushed down the toilet, they ended up at a water-treatment plant. Another common endocrine disruptor is nonylphenol (NON-ul-FEE-nul). It’s a breakdown product of certain surfactants. (Surfactants are chemicals that let liquids mix that would not ordinarily do so.) The problem: Nonylphenol, too, can mimic estrogen.

Story continues below image

Some male rainbow darters exposed to these pollutants produced eggs in their testes. This took a lot of energy. That reduced the energy available for them to make sperm. Affected fish may have made damaged sperm — or no sperm at all. Eggs laid in the water by females won’t mature and hatch unless males release sperm to fertilize those eggs. So egg-making by males could cause fish populations to shrink. Oh, and the eggs made by those males: They’re worthless. The bodies of males lack the tubes needed to release those eggs. So the eggs just collect and take up space in the males’ bodies.

Bacteria, bubbles and healthier fish

The good news: Changes to the wastewater-treatment plant in 2013 led to changes in those males.

The plant had always used bacteria to break down harmful chemicals in the water. But workers upgraded the system to give the bacteria more time to break down chemicals. The plant now also bubbled oxygen into the wastewater. This extra oxygen helped the hard-working bacteria grow faster.

Servos and his team tested the water and fish for three years after these water-cleaning changes. As expected, levels of various pollutants dropped. These included the estrogen-mimicking chemicals.

“We don’t know exactly how estrogens are reduced,” Servos says of the water treatment plant. “The key seems to be giving bacteria more time to break down harmful compounds and to feed them oxygen to speed the process.”

And as levels of these chemicals in the water fell, so did the number of feminized males. Within three years, nearly all male fish appeared normal again, inside and out. The researchers suspect the males’ bodies had re-absorbed the useless eggs. The male darters also regained their rainbow colors.

The study shows that although fish may be exposed to endocrine disruptors early in life, those changes may not harm them forever. “That was part of the surprise — [that] adult fish could recover,” says Servos. He doesn’t know whether other species of fish would respond the same way. He suspects many would.

Chris Metcalfe is an environmental toxicologist at Canada’s Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario. He studies materials that can act as poisons in the environment. Metcalfe cautions that not all endocrine disruptors behave the same way. Just because one type can be removed from wastewater doesn’t mean all others will, too.

He also points out that not all urban areas have good water treatment. Some have none; they just spew polluted wastes directly into rivers. And outside of cities, many people rely on underground septic tanks to store water from toilets and showers. Septic tanks filter and capture many pollutants. If people don’t take good care of these systems, wastes can leak from these tanks into groundwater. From there, pollutants can enter downstream rivers, lakes or the ocean.

What the new work shows is that hormone mimics can hurt fish populations, but that good water-cleansing techniques can limit the risk that this happens.