Traces from nuclear-weapons tests offer clues to whale sharks’ ages

Researchers studying growth bands in the fish’s vertebrae find these animals can live at least a half century

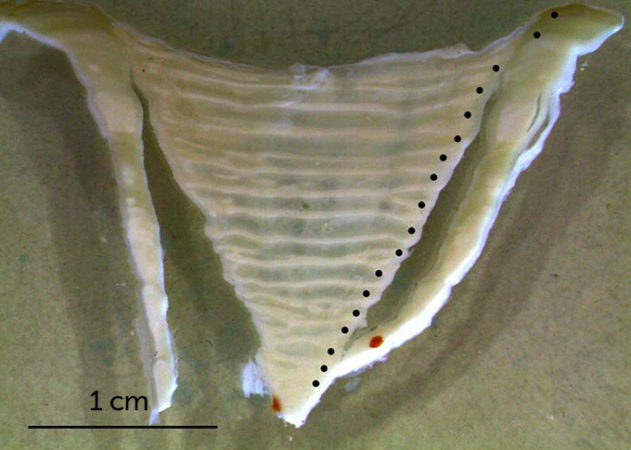

The alternating bands of tissue in whale sharks’ vertebrae are like a tree’s growth rings. They give clues to the animals’ ages.

Wayne Osborn

It’s been surprisingly hard to figure out how old a whale shark is. Now scientists have gleaned clues — ones written in the the sharks’ spines. The clues are visible thanks to the radioactive residues. They were left by nuclear-weapons tests during the Cold War.

As they grow, the vertebrae of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) build up alternating stripes of opaque and see-through tissue. The process is similar to how tree trunks grow rings. Until now, scientists hadn’t known how fast those whale shark vertebrae gain a new growth band. Is it each year? Every six months? Not knowing that made it hard to gauge just how fast these sharks were growing or how long they lived.

Now researchers have measured levels of carbon-14 in the vertebrae of two whale sharks. That carbon is a radioactive isotope (energy-shedding form of the element). Both whales had lived during the 20th century. Soviet and American nuclear weapons tests in the 1950s and 1960s released that carbon-14 as fallout. Over time, it built up in Earth’s atmosphere and oceans — and in the bodies of animals that lived in the oceans. The researchers compared the amount of carbon-14 in the growth bands of whale shark vertebrae with the known carbon-14 levels in surface seawater in different years. That helped the researchers estimate when each band had formed.

The results showed that bands generally grew one year apart. Steven Campana and his team shared what they learned in the April 2020 Frontiers in Marine Science.

Campana is a fisheries scientist at the University of Iceland in Reykjavík. His group also used the total number of growth bands in sharks’ dated vertebrae to figure out their the animals’ ages. One 10-meter (33-foot) male found in Taiwan had been about 35 years old when it died. A female of about the same size, collected in Pakistan, lived to be around 50 years old.

“It is really, really likely that there are older whale sharks out there, simply because we know there are much larger whale sharks,” says Campana. Whale sharks are known to grow up to about 18 meters (59 feet) long.

Campana and his colleagues used vertebral growth-band counts to also figure out the ages of 18 additional dead whale sharks. The animals had all been between 15 and 25 years old. They spanned between 2.7 meters (almost 9 feet) and almost 6 meters (about 20 feet) in length. Based on the lengths of sharks of different ages, the researchers estimated that young whale sharks grow an average of about 20 centimeters (8 inches) per year.

Data on the life span and growth rates of these sharks could be important for finding ways to protect this endangered species, Campana says. “Long-lived animals like whale sharks almost certainly become mature at a relatively old age,” he says. “And their populations are relatively slow to increase their numbers.” So whale-shark populations may not bounce back from threats, such as overfishing, as quickly as species with shorter life cycles.

Fisheries biologist Allen Andrews has a word of caution about the new research. He works at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. There is some uncertainty in the carbon-14 dating technique that Campana’s team used, he says. That’s because radioactive carbon from nuclear tests did not spread evenly throughout the oceans. And “young [whale] sharks disappear for a big portion of their lives,” Andrews adds. If young whale sharks spend much of their time deep underwater, they may not take in the same amount of carbon-14 that is measured at the ocean’s surface.

Researchers could further investigate whale-shark growth by tagging live sharks and then recapturing them, Andrews says. That way, they could measure how much the animals grew from one time to the next.