Concerns explode over new health risks of vaping

Researchers link e-cigs to wounds that won’t heal and ‘smoker’s cough’ in teens

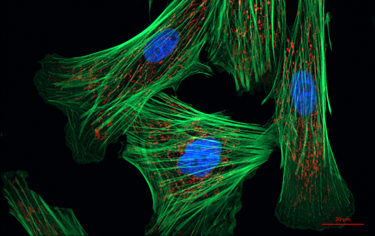

Vaping is not risk-free, especially for kids and teens. A host of new studies have now uncovered worrisome health concerns. For instance, the atomizer shown here can make vapors hotter and riskier to health.

Chaowalit466/iStockphoto

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

When Irfan Rahman talked to young vapers, some complained of bleeding mouths and throats. And these bloody sores seemed slow to heal. Such reports concerned this toxicologist at the University of Rochester in New York. So he decided to investigate what the vapors inhaled from electronic cigarettes might be doing to mouth cells.

Last October, his team showed those vapors inflame mouth cells in ways that could potentially promote gum disease. That gum damage can destroy the tissues that hold teeth in place. So severe gum disease could lead to tooth loss.

But that’s hardly the end of it.

Vapers inhale those same gases and particles into their lungs. Rahman wondered what effects those vapors might have on cells there. One gauge would be to test how long any lung-cell damage took to heal. And his latest data confirm that e-cigarette vapors also make it hard for lung cells to repair damage.

Students as young as 12 or 13 are now more likely to vape than to smoke. Many are under the impression that because e-cigs don’t contain tobacco, they pose little risk to health. Wrong.

Over the past few months, research has turned up evidence that vaping can pose many brand new risks. The vapors mess with immunity, some studies show. “Smoker’s cough” and bloody sores have begun showing up in teen vapers. The hotter a vaped liquid gets, the harsher its effects on human cells. And a relatively new vaping behavior called “dripping” ups the heat. This threatens to intensify a teen’s risks from those vapors.

Some new data even suggest that e-cig vapors may contain cancer-causing chemicals.

“There are a lot of potentially harmful substances in e-cigarettes. If you’re a teen with your whole life in front of you, why take that risk?” asks Rob McConnell. He’s an internal medicine specialist at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles.

The newly emerging data suggest that adolescents ignore these risks at their peril.

Impaired wound healing

Cells in the body face constant damage from foreign substances, infections and injury. Most times, nothing bad happens to their host. That’s because the body has a system in place to heal itself. Most major organs have special cells — fibroblasts (FY-broh-blasts) — that repair damaged or injured tissue.

Fibroblasts make up the connective tissues that keep organs in place. But when injured, these cells morph into wound-healers. “If you cut your hand, fibroblasts are the guys that are going to come in and help heal it,” explains Rahman.

In their wound-healing form, fibroblasts at the edges of a cut will shrink. This causes the wound to close up. This squeezing or contraction of the skin takes a lot of energy. Fortunately, fibroblasts are powered by cellular engines. Called mitochondria (My-toh-KON-dree-uh), these tiny powerhouses turn food (sugar) into fuel.

In the lab, Rahman and his colleagues grew lung fibroblasts in Petri dishes. Then they cut into the community of growing cells to mimic a wound. Afterward, they exposed the growing cells to e-cigarette vapors.

As expected, the fibroblasts morphed into wound-healing cells. But unexpectedly, they didn’t close up the cut. Curious, Rahman looked more closely at the cellular machinery. Some mitochondria had been destroyed. The fibroblasts simply had run out of the energy they needed before they could successfully squeeze the wound closed.

Rahman’s team described its findings March 3 in Scientific Reports.

It’s not clear yet if the fibroblast damage that Rahman showed in the lab signals that wounds will heal more slowly in people who vape. After all, in the lab, scientists can manipulate one variable at a time while holding other factors constant. But in the body, many processes will be at work all at once. This can make it harder to tease out whether such lab tests mimic well what would happen to an otherwise healthy person.

And that’s why Rahman now hopes to compare rates of wound healing in people who vape to rates in those who don’t. For now, however, he’s worried that what he saw in the lab may indeed mimic risks to people.

Smoker’s cough becomes vaper’s cough?

Inhaling pollution can irritate the lungs. And when the assaulting particles are breathed in regularly, the lungs tend to respond by triggering a cough that won’t go away, explains McConnell at USC. He has been studying the effects of air pollution in kids. Inhaling irritating particles or gases may lead to bronchitis (Bron-KY-tis). That’s when the airways that channel oxygen to the lungs become irritated and inflamed.

Bronchitis may cause wheezing, too, and coughs that bring up thick mucus known as phlegm (FLEM). The germs that cause colds, flu and bacterial infections can sometimes trigger bronchitis. So can breathing in heavily polluted air, tobacco smoke or certain chemical fumes.

When these symptoms don’t go away, the bronchitis is called chronic (KRON-ik). And cigarette smoking is its most common cause. That’s why chronic bronchitis is typically referred to as “smoker’s cough.”

McConnell’s team decided to look for signs of bronchitis in vaping teens. After all, he explains, “There are a lot of these irritants in e-cigarette vapor.”

The researchers asked 2,000 students in the Los Angeles, Calif., area about their vaping habits. All were in their last two years of high school. The researchers also asked the teens about any respiratory symptoms. These could include coughs or phlegm.

Anyone who reported a daily cough for at least three straight months was judged to have chronic bronchitis. A student with persistent phlegm or congestion for three months or more that was not accompanied by a cold or flu also was suspected of having chronic bronchitis.

About 500 of the students said they had vaped at some point. And about 200 had vaped within the past 30 days. Those recent vapers were about twice as likely to have chronic bronchitis as were kids who had never vaped, the researchers report. Students who had vaped in the past, but not in the last month, also were about as likely as current vapers to have chronic bronchitis.

The researchers looked for other possible causes of the teens’ persistent coughs and phlegm. One of these was local air pollution. They also looked at the teens’ exposure to triggers for allergic asthma. Such triggers can include molds and pet dander. Yet even accounting for all of that did not erase the link between vaping and chronic bronchitis.

The findings, first announced in November, will appear in an upcoming issue of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

These data also support what has been seen in studies conducted in human and animal cells, Rahman notes.

It worries McConnell that vapers show some of the same lung symptoms as cigarette smokers. It also worries him that more teens are taking up vaping. E-cigarette use grew an astounding 900 percent among high school students between 2011 and 2015.

Cigarette smokers with chronic bronchitis often develop permanent lung damage as they get older. Researchers don’t know yet whether long-term vapers will too.

“People haven’t been using e-cigarettes long enough to answer that question,” observes McConnell. E-cigarettes have been available in the United States only since 2007.

Teens lured by fruity flavors

A third new study investigated the role of flavor in e-cig use, especially by teens.

E-cigarettes don’t burn tobacco as true cigarettes do. Yet they still are considered tobacco products. That’s because the liquids that are vaporized in e-cigarettes usually contain nicotine. It’s the addictive substance found in tobacco leaves — one that also gives cigarettes their stimulant effect, or “buzz.”

A team of researchers led by Li-Ling Huang at the University of North Carolina (UNC) in Chapel Hill wanted to know whether the e-liquid’s flavor affected how safe people thought vaping was. To do this, they reviewed 40 studies on flavored tobacco products. These included flavored e-cigs. Most of the studies had been conducted between 2010 and 2016.

Both tobacco users and non-users said tobacco products were more appealing when the products had pleasing flavors. Younger people were particularly interested in fruity and candy-flavored products. In fact, this is one reason the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2009 banned cigarettes flavored with anything but menthol. It was to limit their appeal to kids.

“It turns out that an interest in flavors is one of the main reasons that youth try e-cigarettes,” says Adam Goldstein of UNC. An author of the new study, his past work had focused on tobacco use.

Teens also tended to perceive pleasantly flavored products as less harmful than tobacco-flavored ones, his team’s data show. Their findings are due to appear in an upcoming issue of Tobacco Control.

Goldstein says it’s important to note that just because something doesn’t taste like tobacco doesn’t mean it is safe. Studies have shown that some flavor compounds in e-liquids (such as cinnamon extract) appear to become harmful when heated in an e-cigarette.

Review studies like this one point to potentially important trends. Such studies may help shape new policies, Goldstein says. (Policies are actions taken by government, companies or other large groups.)

Goldstein believes that removing flavorings would be one way to discourage kids from experimenting with e-cigs. “Research suggests that if you remove the flavors, far fewer youth around the country would use any tobacco product,” he says. And that would put fewer kids at risk for vaping-related damage to the mouth and lungs.

Toxic metals in e-liquids

At the heart of every e-cigarette is a metal coil used to heat up the flavored e-liquid that will become a vapor. Scientists have found a number of harmful chemicals in e-cigarette vapors. Some can cause cancer. Among these are formaldehyde (For-MAAL-de-hide) and acetaldehyde (Ass-et-AAL-de-hide). Previous studies had shown that some e-liquids that were considered harmless could become toxic — but only after they were heated by an e-cig’s especially hot coil.

Now Catherine Hess of the University of California, Berkeley, and her colleagues have turned up traces of toxic metals in the e-liquids used in five different brands of e-cigarettes. Those liquids came packaged from the manufacturer in non-refillable e-cigs. The scientists chose to look at these “first-generation” e-cigarettes because they are inexpensive, which can make them especially attractive to teens.

The most concerning of these metals were nickel, chromium and manganese. The amounts of them varied between brands. All three metals occur naturally in rock formations all over the planet. Inside the body, though, they can cause trouble. Research suggests that nickel and certain forms of chromium may cause cancer. Manganese can harm the nervous system.

The researchers measured only the amount of toxic metals in the e-liquids, not how much ended up in the vapor. “More research is needed to see whether e-cigarette users are being exposed to these chemicals when they inhale — and what the long-term effects of those exposures might be,” says Rahman, who was not involved in this study.

Hess’s team published its results in the January Environmental Research.

Another new study turned up benzene in e-cig vapors. This chemical is known to pose a cancer risk to people. Chemist James Pankow and his team at Portland State University in Oregon don’t know the chemical’s source. Benzene is, however, a toxic component of cigarette smoke. The levels in e-cig vapors were not as high as in cigarette smoke. Still, Pankow argues, that does not mean that vaping poses little benzene risk.

“The fact that vaping can deliver benzene levels many times higher than those found in the ambient [air] — where it’s already recognized as a cancer risk — should be of concern to anyone using e-cigarettes,” he says. Higher-power e-cigs, which burn hotter, produced the most benzene in the Portland State tests. So, Pankow now urges, “Please stay away from high power if it’s available on your device.”

His team published its findings March 8 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Concerns about dripping

Newer-generation e-cigs allow users to choose — and change — what flavorings they heat up in their devices. Most vapers choose a liquid with nicotine (that addictive, stimulant found in tobacco). To get the biggest nicotine hit from each puff, some vapers take the outside cover off of their e-cigarette and use an eyedropper to “drip” the liquid directly onto the device’s coil.

E-liquids reach higher temperatures when dripped directly onto the coil. This also creates a bigger vapor cloud and provides a bigger throat hit. A new study now raises special concerns for teens who drip.

Allowing the liquid to get superhot can transform harmless chemicals in the e-liquid into toxic ones. (Note: At least one recent study showed that the hotter the vaped liquid became, the more likely it was to undergo such a toxic transformation.) And dripping makes this super-heating likely. Some people even use attachments, called atomizers, to do this more effectively.

Vaping hobbyists that do smoke tricks may have popularized dripping, says Suchitra Krishnan-Sarin. A psychiatrist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn., she’s been studying vaping behaviors in teens. Many now drip, she and her colleagues report.

This team surveyed 1,080 Connecticut high schoolers who said they vaped. One in every four teen vapers said he or she had tried dripping.

This is the first time any study has reported on the popularity of dripping in teens. (Researchers don’t yet know how common dripping is among adults.) The new statistics appear in the February Pediatrics.

Most teens who dripped said they had hoped it would let them make thicker vapor clouds or give the vapor a stronger taste. At present, little is known about the health risks of this type of vaping, Krishnan-Sarin notes.

And that worries her. “There’s great concern,” she says, “that kids are being exposed to higher levels of known carcinogens this way.” Researchers don’t yet know if this is true. And that’s because no one has yet studied whether more of these compounds get into the body when people drip instead of vaping normally.

For now, Krishnan-Sarin says a bigger vapor cloud or more flavorful hit probably isn’t worth the risk. “You don’t know what you’re exposing yourself to,” she points out, and no one should assume that the e-liquids and the vapors they generate are harmless.