Cool jobs: Brainy ways to battle obesity

Scientists search for smarter ways to help people avoid overeating

The brain — often without thought — plays a pivotal role not only in determining when we feel hungry or full, but also in which foods appeal to us most.

george tsartsianidis/ iStockphoto

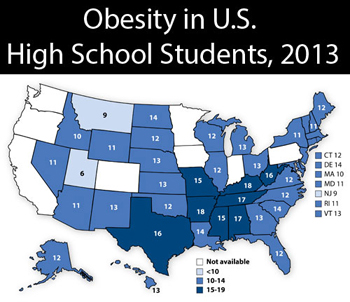

About one in every six children and teens throughout the United States are very overweight, meaning obese. Some one-third of adults are, too. Those data come from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Ga. Carrying those extra pounds significantly ups the risks for disease. High blood pressure, diabetes, liver disease and breathing problems are just a few of the conditions linked to excess body weight.

In short, obesity is an extra-large problem.

Most people know they should not eat too much — especially sugary and fatty foods. But “just knowing what they’re supposed to do is not enough,” says David Cavallo. He’s a dietician who does research on nutrition at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. “There need to be other things in place to help people make good decisions,” he says.

And science can help. Here’s how three scientists are focusing on the brain to rein in the expansion of our waistlines.

Tapping into social media

Cavallo was working in advertising and online sales when he first started reading up on nutrition. In his spare time, he competed in bicycle races. And hoping to get the edge on his competition, he decided to eat better. Over time, his interest in nutrition overtook his interest in sales. So Cavallo left his job to study public health and nutrition at the University of North Carolina (UNC) in Chapel Hill.

“I really fell in love with doing research,” he says.

While there, in graduate school, he probed how technology might help teens make better food choices at lunch. The research team that he worked with created a way for high school students to get menu information online. Kids then could text lunch orders to the cafeteria in advance. “Students are obviously very involved” in using their smartphones for texting, accessing social media, and other activities, Cavallo says.

His research team tracked how many kids used the system and what they ordered. Teens could buy any item from the lunch menu. However, the system was designed so that it would be easier to order a healthier, balanced meal. The researchers thought that the advance planning might encourage students to make healthier food choices. They also thought that by tapping into something teens already liked — smartphone apps — it could save the kids precious time during their lunch period.

The UNC team has finished collecting data and now is analyzing its results. The researchers are looking at whether the system was popular and, most importantly, whether it helped students make healthier food choices.

At Case Western, Cavallo’s research now is looking at how technology might be used to improve food choices. He focuses on social media. Recently, he started a project that will analyze how people respond to Facebook posts by a government nutrition program. Among other things, he and his colleagues want to see what types of messages get the most “likes” and “shares.”

Overall, his goal is to help government agencies run more effective social media campaigns about healthy eating. Ideally, Cavallo says, such programs can help people make better decisions about food.

Fighting mindless eating

Not all eating is the result of conscious decisions, however. “A lot of our behavior is also automatic,” says Aner Tal. He’s a social scientist at the Cornell University Food and Brand Lab in Ithaca, N.Y. Tal studies consumer behavior and food psychology: “What we try to focus on in the lab is finding easy ways to combat obesity.”

Much of their work aims to understand — and then curb — what his team calls “mindless eating.”

In one study, Tal and his team tracked how much college students snacked while watching television. One group of students watched 20 minutes of a talk show. Another group watched 20 minutes of an action movie. A third group watched the action movie segment with the sound muted.

Compared to the talk show group, those listening to the action movie ate more food. Much more. On average, the snacks they downed weighed nearly twice as much and had 65 percent more calories. Even the group watching the movie without sound ate more than those watching the talk show. While watching the muted movie, the students ate about a third more food, by weight. The snacks also contained about 46 percent more calories than those consumed by the talk-show watchers.

Such findings don’t mean people should stop watching action movies. But they do show how something that demands a lot of our attention can make it harder to focus on what goes into our mouths.

To stop mindless eating, Tal says, “We can try to engineer the situation ahead of time.” If it’s too hard to stop eating in front of the TV, he suggests pre-measuring snacks into small bowls. Then eat no more than a bowl’s worth. Or, try cutting up veggies ahead of time instead of grabbing a bag of chips during the middle of a TV show.

Some of Tal’s other projects explore factors affecting how people shop for food. One study found that people tend to make less healthy choices if they shop for groceries when they’re hungry.

“Knowing that happens can let you exercise some control,” he points out. For instance, shoppers might write a list when they’re not hungry and stick to it at the store. Or, they can grab a small healthy snack before heading out. That way they’re not starving as they walk down the aisles.

Tal also found that when stores offered shoppers free samples of fresh apple, they bought healthier foods than when people were given a free cookie.

Food descriptions made a difference too. People who sampled “healthy, wholesome chocolate milk” purchased a more healthful mix of foods than those who tried “rich, indulgent chocolate milk” — or even no sample at all. He and his team published their results, last May, in Psychology & Marketing.

Finding connections

Food choices and eating habits are just some reasons why people may become overweight. The way our brains and bodies function also plays a big role.

Ana Domingos works at the Gulbenkian Institute of Science in Oerias, Portugal. As a neurobiologist, she studies how the brain and rest of the nervous system affect behaviors and bodily functions. In her case, she probes how these can relate to obesity. To do that, she and her team use a fairly new technology called optogenetics.

Opto– refers to light. Genetics deals with the biological instructions in our genes. The technology uses light to either turn on or shut down functions of some genes in cells that have been modified in the lab. For this work, Domingos works with mice. Indeed, the bodies of mice and humans have many similar features and functions.

Both mice and people prefer natural sugars, such as honey, to artificial (sugar-free) sweeteners. Sugar provides energy. Artificial sweeteners do not. To show why and how real sugar wins out, Domingos and other scientists mapped a pathway among brain cells. Optogenetics let them see what was going on.

When mice or people eat sugar, certain neurons send signals to the brain. Some of those signals end up in pleasure centers. Others go to the brain’s lateral hypothalamus (HY-po-THAL-uh-mus). That’s a part of the brain that controls feelings of hunger. Signals it receives can tell an organism it’s full, so it is time to stop eating.

Eating fake sugars doesn’t send those same signals to the brains of mice and people. But in 2013, Domingos and her team reported that they could use light to turn on a signal from certain neurons — or nerve cells — along the “I’m-getting-full” pathway. This made mice switch their preference, choosing fake sugars over natural ones. The finding showed how signals moving through the brain — and unrelated to thought — control that choice.

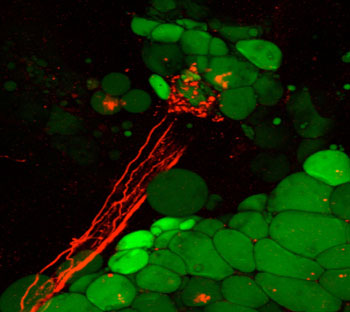

A second study helped show how the body breaks down fat. Fat is stored in a type of cell known as an adipocyte (Ah-DIP-oh-syte). These fat cells are linked to the brain by neurons that are directly attached to them. When the brain signals those neurons, they release a chemical called norepinephrine (NOR-ep-ih-NEF-rin). It tells the adipocytes to break down their stored fat. And this makes the fat cells shrink. If that happens throughout the body, “you become less chubby,” Domingos notes.

Her team used optogenetics to trigger this fat-breaking action. Instead of waiting for a signal to come from the brain, they used light to stimulate neurons near the fat cells. Those neurons then released the fat-breakdown chemical. Domingos says these data show that nerve cells in the brain talk directly to fat cells. She and her colleagues published their study in Cell on September 24, 2015.

These researchers hope a medicine might eventually be able to similarly trigger adipocytes to break down and eliminate much of the excess fat they might hold. “This is something that my lab is actively working on,” Domingos says.

Obesity is a serious public health problem. Yet our own minds may already hold some of the solutions. As scientists like Domingos, Tal, Cavallo and others are learning, brain science is a smart way to help fight obesity and keep us all healthy and trim.

This is one in a series on careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics made possible with generous support from Alcoa Foundation.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

adipocyte A cell dedicated to storing excess fat until it those fats may be later needed to fuel bodily activities.

app Short for application, or a computer program designed for a specific task.

behavior The way a person or other organism acts towards others, or conducts itself.

biophysics The study of physical forces as they relate to living things. People who work in this field are known as biophysicists.

cell The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism. Typically too small to see with the naked eye, it consists of watery fluid surrounded by a membrane or wall. Animals are made of anywhere from thousands to trillions of cells, depending on their size.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC An agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC is charged with protecting public health and safety by working to control and prevent disease, injury and disabilities. It does this by investigating disease outbreaks, tracking exposures by Americans to infections and toxic chemicals, and regularly surveying diet and other habits among a representative cross-section of all Americans.

data Facts and statistics collected together for analysis but not necessarily organized in a way that give them meaning. For digital information (the type stored by computers), those data typically are numbers stored in a binary code, portrayed as strings of zeros and ones.

dietician (or dietitian) An expert who works out what an individual should eat to attain and maintain a healthy weight. Dieticians also can work out meal plans to help people with special medical problems, such as heart disease and diabetes.

gene (adj. genetic) A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves

genetic engineering (or genetic modification) The direct manipulation of an organism’s genome. In this process, genes can be removed, disabled so that they no longer function, or added after being taken from other organisms. Genetic engineering can be used to create organisms that produce medicines, or crops that grow better under challenging conditions such as dry weather, hot temperatures or salty soils.

graduate school Programs at a university that offer advanced degrees, such as a Master’s or PhD degree. It’s called graduate school because it is started only after someone has already graduated from college (usually with a four-year degree).

hypothalamus A region of the brain that controls bodily functions by releasing hormones. The hypothalamus is involved in regulating appetite through release of appetite-suppressing hormones.

mammal A warm-blooded animal distinguished by the possession of hair or fur, the secretion of milk by females for feeding the young, and (typically) the bearing of live young.

nerve cell or neuron Any of the impulse-conducting cells that make up the brain, spinal column and nervous system. These specialized cells transmit information to other neurons in the form of electrical signals.

neuroscience Science that deals with the structure or function of the brain and other parts of the nervous system. Researchers in this field are known as neuroscientists.

norepinephrine A type of stress hormone secreted by the adrenal glands. It constricts blood vessels. It also increases the force and rate at which the heart contracts.

nutritive value A calculation of how much energy, nutrients or other physiological benefits a given amount of food can provide.

nutrients Vitamins, minerals, fats, carbohydrates and proteins needed by organisms to live, and which are extracted through the diet.

obesity Extreme overweight. Obesity is associated with a wide range of health problems, including type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.

optogenetics A technique that uses light to better understand genes and cells in the nervous system, especially the brain. Recent research is using the technology to study other types of cells and tissues too.

overweight A medical condition where the body has accumulated too much body fat. People are not considered overweight if they weigh more than is normal for their age and height, but that extra weight comes from bone or muscle.

physiology The branch of biology that deals with the everyday functions of living organisms and how their parts function. Scientists who work in this field are known as physiologists.

psychology The study of the human mind, especially in relation to actions and behavior. Scientists and mental-health professionals who work in this field are known as psychologists.

smartphone A cell (or mobile) phone that can perform a host of functions, including search for information on the Internet.

social media Internet-based media, such as Facebook, Twitter and Tumblr, that allow people to connect with each other (often anonymously) and to share information.

social network Communities of people (or animals) that are interrelated owing to the way they relate to each other. In humans, this can involve sharing details of their life and interests on Twitter or Facebook, or perhaps belonging to the same sports team, religious group or school.

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)