Cool Jobs: Keeping TV science honest

Advisors for Bones, Chicago Med and The Big Bang Theory reveal their secrets

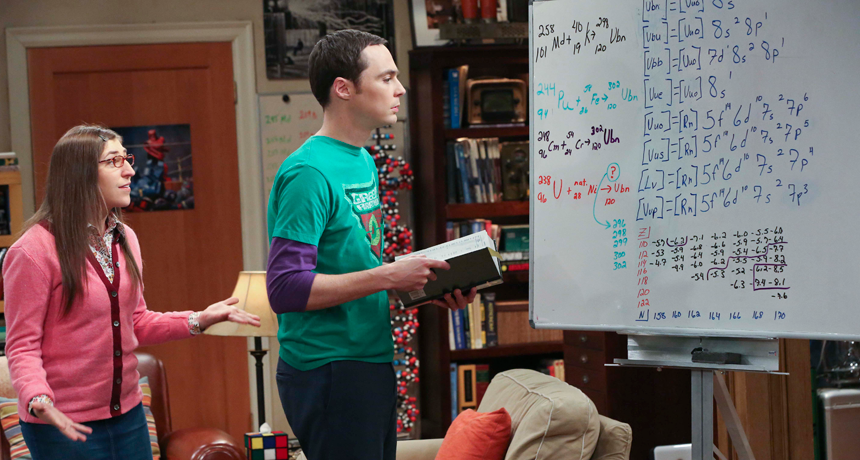

Amy Farrah Fowler (played by Mayim Bialik) and Sheldon Cooper (played by Jim Parsons) eye equations on The Big Bang Theory. Advisor David Saltzberg makes sure that the pictured equations are right, along with most of the rest of the science on this show.

Michael Yarish/CBS

By Gerri Miller

It takes a lot to gross out Donna Cline. As the science advisor for the Fox TV show Bones, she’s used to seeing real-looking mutilated corpses. But when live worms emerged from a fake intestine in an autopsy scene, she almost lost her lunch. “I’m okay with decomposing bodies — I’ve seen them for real. But I don’t like worms,” she confesses.

Cline pretty much loves everything about the job she’s had for the past 11 years. It’s something she shares with the other technical advisors you’ll meet in this story. They give you the inside scoop on what it takes to make TV science and medicine realistic. And they share some behind-the-scenes “cheats” that make popular shows seem more real than they are.

Here are some of the people who inject a dose of reality into make-believe.

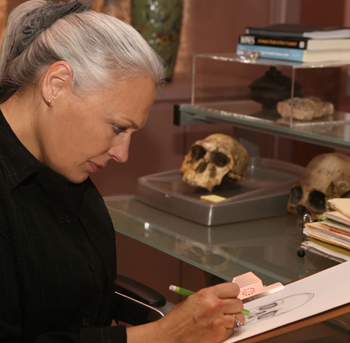

Bones: Donna Cline

Cline has worked on Bones — a murder mystery and forensics drama — from the day it started. And, she says, “It’s incredibly entertaining for me to see how the science is woven into the drama.” She’s on the set whenever there’s a crime scene or lab research at the fictional Jeffersonian Institute. She also helps explain technical details to the actors. “I never know what’s going to happen next,” she says, “or what I’m going to be asked to do.”

Cline also works closely with the show’s writers on every script. First, the writers send her an outline several weeks ahead of filming. At this point, she starts “researching every detail in terms of forensics and anatomy.” Later, she meets with the people who lead departments such as makeup, visual effects and wardrobe to work out details. Then there’s a final meeting to make adjustments before shooting the scenes.

The writers are very open to Cline’s suggestions, she says. “I give them ideas, and they can run things by me.” One time, she told them about a spider bite infection that can cause bone injury. Sure enough, it showed up in the plot.

She also makes sure the right character is doing the right task. If it has to do with bones, it’s forensic anthropologist Temperance Brennan (played by Emily Deschanel). If it involves tissues and organs, it’s pathologist Camille Saroyan (played by Tamara Taylor).

Cline works closely with the cast, showing them how to use tools properly. For each episode, she provides a guide to science terms. She lists those terms scene-by-scene and alphabetically, with an illustration of each item. As a former medical illustrator, that’s both easy for her and fun.

As a child, she always “wanted to know how things worked biologically.” She later got a master’s degree in biomedical illustration. Along the way, she dissected cadavers and drew tissues and organs. She even illustrated a surgical textbook. She then became a storyboard artist and medical advisor for movies. Today she does both jobs on Bones.

For reference, Cline checks a huge library on science and forensics. It includes books on gunshot wounds, embalming and blood-splatter patterns. If these can’t answer a question, she has a network of specialists to call upon.

Cline loves being able to inject cutting-edge science into TV shows, but only as long as “it works for the storyline.” Sometimes, she admits, she and the writers have to make some sort of compromise. “But,” she adds, “it’s always well-thought-out compromises that aren’t unbelievable or tacky.”

A bit of an exaggeration?

So where do they stretch the truth? Let’s start with the characters’ jobs.

In reality, Cline says, forensic anthropologists who work for a medical examiner’s office would spend their time in the field, retrieving evidence and bodies. It’s not realistic to have Brennan working so closely with the FBI on such a regular basis, Cline says.

More and more, real crime labs are using the kind of computer-assisted facial reconstruction that Angela Montenegro (played by Michaela Conlin) does on the show. Cline says the technology probably wouldn’t produce faces that are nearly as precise as the show suggests. “But,” she adds, “I don’t doubt that real life will catch up.”

In the real world, it takes much longer to get answers about evidence than it does on TV. DNA analysis can take weeks, Cline notes. But on the show, “We get them back in a couple of hours.”

Jack Hodgins (played by T.J. Thyne) is an insect expert, or entomologist. He analyzes maggots on cadavers to find out when someone died — which is actually possible. “But we don’t show the whole procedure,” she says. Most people would find the details of evidence analysis long and tedious. “We’d put everyone to sleep,” Cline suspects.

The insect larvae in those scenes are sometimes real and sometimes not. Maggots that need to move in a scene are mealworms; ones that don’t are grains of orzo. “We sometimes use coffee beans for bugs,” Cline says.

Another substitute involves skeletons. “The bones are resin,” she reveals. “We buy them from a company that molds them from real bones. We can order males, females, teenagers, kids.” They can even ask for bones from different races.

Sometimes, for effect, fire victims’ bodies are burned more than they would be in real life. At other times, the wackiest things are absolutely real. Cline remembers a Bones crime scene showing a tree that blew over, revealing a skeleton in its roots. “The tree had grown over the buried body,” Cline says. “That really happened.”

Chicago Med: Andrew Dennis

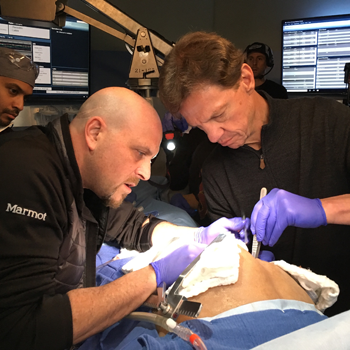

Combining real medicine and make-believe medicine makes life interesting for doctor Andrew Dennis. He’s a trauma and burn surgeon at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, Ill. He’s also the medical advisor to the NBC series Chicago Med.

Dennis doesn’t just oversee the many medical procedures on the show. He also meets with the writers to review scripts and tweak them for medical accuracy. His job is to make sure “the storylines are appropriate for the characters,” he says, “and are as real as possible.”

This part-time job puts him on set about three days a week. He makes sure anything photographic — including x-rays — looks right. He also ensures that the actors move in the right way during surgery scenes. In fact, he choreographs the surgeries. Unless a scene involves delivering a baby, that is. Then, his wife Melissa Dennis, an obstetrician-gynecologist, takes over. He may also call in specialists to help with other things outside his comfort zone, such as brain and heart operations.

Dennis discusses story ideas with colleagues at his hospital. Some ideas come right from the headlines. They may be “unique cases,” he says, “not something most doctors have ever seen.” The case of an icicle piercing a patient’s head is a good (and all-too-true) example.

“Our rule is that if it’s published somewhere, it’s fair game, as farfetched as it might be,” he says.

In surgical scenes, the show’s extras are real medical students, doctors and nurses. And Bobbin Bergstrom is on the set full-time to supervise. She’s a nurse and medical consultant “in charge of making sure the details work,” notes Dennis. “We are a team.”

Early on, he put the cast through a three-day “medical boot camp.” The actors learned everything from how to give patients stitches and IVs to how to put on sterile gloves and do CPR. Guest actors go through a modified form of the boot camp.

But despite everything Dennis does to be medically accurate, there’s a lot that just can’t be done on TV.

As you might expect, “You can’t put real needles in actors. All that is done artificially.” And if the task calls for something very technical, “We’ll do it as an ‘insert,’ where you’ll see my hands or one of my colleagues’ hands,” says Dennis. “If it looks like we’re sticking a needle into someone’s groin, there’s usually a small prosthetic over that area (and a safety plate behind it).” And those needles don’t really go into someone’s skin: they’re retractable. “Safety on the set is paramount,” Dennis says. “We use dull knife blades, and defibrillators are [modified] so no one gets shocked.”

He works with the special-effects department to create all of these elements and make sure they’re right for the surgery shown. In all operations, the organs are made of silicone, and the blood is a mix of corn syrup and food coloring.

In real operating rooms, surgeons and nurses wear hats and masks. “But producers want to see actors’ faces, so we cheat that,” says Dennis. For the same reason, TV shows lower the drape that normally would cover a patient’s face.

Not surprisingly, things happen a lot faster on Chicago Med than they do in real life. Lab results come back in minutes. Surgery patients wake up quickly. “We do what we have to for the dramatic needs,” Dennis says. But he estimates that the show is 85 percent accurate. “For a medical drama, I think that’s pretty high.”

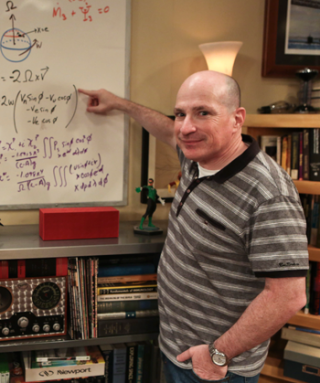

The Big Bang Theory: David Saltzberg

Since 2007, CBS’ The Big Bang Theory has poked fun at the quirkier side of scientists. Physicists Sheldon Cooper (played by Jim Parsons) and Leonard Hofstadter (Johnny Galecki), aerospace engineer Howard Wolowitz (Simon Helberg) and astrophysicist Raj Koothrappali (Kunal Nayyar) provide plenty of laughs. But there’s real science behind the humor on this sitcom. And from the start, David Saltzberg has been the man responsible for getting it right.

“Sometimes it’s as simple as writing some equations on the whiteboards in the boys’ apartment,” he says. At other times, “it’s an experiment they might be doing or an invention they might be developing.” And he should know. Salzberg teaches physics and astronomy at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Saltzberg isn’t on set every day, just on days the show is taped. But if there’s a lot of science in an episode, he says, “I’ll come to a rehearsal and make sure the dialog, diagrams or pictures are right.”

The scientist stays up to date with news from the American Physical Society so he can make story suggestions. They need to be factual, but not too out-there. “The characters live in our world,” Saltzberg says. When the writers come up with an idea that doesn’t ring true, he says, “I give options.” In one case, when he explained to the writers that a theory wasn’t well established, “the next version of the script had them disproving the idea.”

If a script involves the life sciences, he defers to Mayim Bialik. She’s the real-life neuroscientist who plays Amy Farrah Fowler. “She makes sure we don’t make any mistakes. And I certainly don’t need to tell her how to pronounce anything!” He says that he doesn’t have to tell Jim Parsons either, despite the complicated scientific speeches he often has to make.

Cameo appearances by real scientists make The Big Bang Theory more authentic. Guests have included astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson, black-hole expert Stephen Hawking and engineer Bill Nye the Science Guy. But Saltzberg admits to some minor cheats.

For example, the California Institute of Technology is a real university — but the way it works on the show isn’t realistic. Viewers never see the characters’ supervisors, Saltzberg points out. And in most real science projects, researchers would be working together on teams, not working alone as they do on the show.

Lasers are another example. In real life, you usually can’t see a laser’s beam. But that would not be visually interesting. “So you show the laser beam for the audience,” Salzberg says.

This physicist has taught at UCLA for 20 years, and now often lets the show borrow his school’s equipment and materials. Sometimes his colleagues and students even get to visit the set. For Saltzberg, moonlighting in show business is a lot of fun. Once, a University of Hawaii astronomer even surprised Saltzberg and The Big Bang Theory cast and creators by naming asteroids after them.

Social media weighs in

No matter how closely the advisors scrutinize the scripts, mistakes will happen.

Donna Cline remembers a line about a “fractured cerebellum.” The problem: That is medically impossible. The cerebellum is soft tissue, so it can’t be cracked. The script should have called it “damaged” or “injured” instead. “I don’t know how that happened,” Cline says. But she sure heard about it afterward.

Andrew Dennis welcomes input from social media. “We know that some of the things we tackle are controversial,” he says. That’s because the show wants to encourage discussion. It’s one more thing Dennis has to think about, besides accuracy.

David Salzberg recalls the script from an early episode that mentioned a real scientist named Amos Dolbear, but called him Emil by mistake. Salzberg still feels bad about it. But he’s glad that the Internet and social media exist now to keep technical advisors on their toes.

“Everyone can rewind and freeze frame and go into chat rooms and make fun of you if you get something wrong,” Dennis says. As a result, “Today, you’re hard pressed to find a show that doesn’t try to get it right.”

This is one in a series on careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics made possible with generous support from Alcoa Foundation.