The cool science of hot peppers

Chilies can make food safer, relieve pain and may even help people lose weight

Many chili peppers look as fiery as they taste! A single chili pepper can be enough to spice up an entire family’s meal.

liz west/Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Shiny green slices of jalapeño pepper adorn a plate of nachos. Chomping into one of those innocent-looking chilies will make a person’s mouth explode with spicy fireworks. Some people dread and avoid the painful, eye-watering, mouth-searing sensation. Others love the burn.

“A quarter of the world’s population eats chilies every day,” notes Joshua Tewksbury. He is a biologist who spent 10 years studying wild chili peppers. He also happens to enjoy eating hot, spicy food.

Chili peppers do much more than burn people’s mouths. Scientists have discovered many uses for the chemical that gives these veggies their zing. Called capsaicin (Kap-SAY-ih-sin), it’s the main ingredient in pepper spray. Some people use this weapon for self-defense. The spray’s high levels of capsaicin will burn the eyes and throats of attackers — but won’t kill people. In smaller doses, capsaicin can relieve pain, help with weight loss and possibly affect microbes in the gut to keep people healthier. Now how cool is that?

A taste for spice

Why would anyone willingly eat something that causes pain? Capsaicin triggers a rush of stress hormones. These will make the skin redden and sweat. It can also make someone feel jittery or energized. Some people enjoy this feeling. But there is another reason why chilies show up on dinner plates the world over. Hot peppers actually make food safer to eat.

Before refrigerators, people living in most hot parts of the world developed a taste for spicy foods. Examples include hot Indian curries and fiery Mexican tamales. This preference emerged over time. The people who first added hot peppers to their recipes probably had no idea chilies could make their food safer; they just liked the stuff. But people who ate the spicy food tended to get sick less often. In time, these people would be more likely to raise healthy families. This led to populations of hot-spice lovers. People who came from cold parts of the world tended to stick with blander recipes. They didn’t need those spices to keep their food safe.

Why chilies hurt

The heat of a chili pepper is not actually a taste. That burning feeling comes from the body’s pain response system. Capsaicin inside the pepper activates a protein in people’s cells called TRPV1. This protein’s job is to sense heat. When it does, it alerts the brain. The brain then responds by sending a jolt of pain back to the affected part of the body.

Normally, the body’s pain response helps prevent serious injury. If a person accidentally places fingers on a hot stove, the pain makes him or her yank that hand back quickly. The result: a minor burn, not permanent skin damage.

People, mice and other mammals feel the burn when they eat peppers. Birds do not. Why would peppers develop a way to keep mammals away but attract birds? It ensures the plants’ survival. Mammals have teeth that smash seeds, destroying them. Birds swallow pepper seeds whole. Later, when birds poop, the intact seeds land in a new place. That lets the plant spread.

People managed to outsmart the pepper when they realized that a chili’s pain doesn’t cause any lasting damage. Those with pepper allergies or stomach conditions do need to stay away from chilies. But most people can safely eat hot peppers.

Pain fights pain

Capsaicin does not actually damage the body in the same way that a hot stovetop will — at least not in small amounts. In fact, the chemical can be used as a medicine to help relieve pain. It may seem bizarre that what causes pain might also make pain go away. Yet it’s true.

The human body is good at repairing itself, however. Eventually, the pain will fix this pain system and can once again send pain alerts to the brain. However, if the TRPV1 protein is activated often, the pain system may not get a chance to repair itself in time. The person will only feel discomfort or burning at first. Then he or she will experience relief from other types of pain.

For example, people with arthritis (Arth-RY-tis) regularly have pain in their fingers, knees, hips or other joints. Rubbing a cream containing capsaicin onto the painful area may burn or sting at first. After a while, however, the area will become numb.

Rohacs warns that capsaicin creams don’t seem to soak deeply enough into the skin to totally eliminate pain. He says other researchers are currently testing capsaicin patches or injections. These would likely do a better job at halting pain. Unfortunately, these therapies tend to hurt a lot more than a cream — at least in the beginning. Someone who can tough out the initial discomfort, however, could get relief that lasts for weeks, not hours.

Sweat it out

Chili peppers also may help people lose weight. However, a person can’t simply eat hot, spicy food and expect to shed pounds. “It’s not a magic remedy,” warns Baskaran Thyagarajan. He works at the University of Wyoming in Laramie. As a pharmacologist, he studies the effects of medicines. His team is now working to create a drug to make the body burn through fat more quickly than usual. A primary ingredient: capsaicin.

In the body, capsaicin triggers a stress reaction known as the fight-or-flight response. It normally occurs when someone (or some animal) senses a threat or danger. The body responds by preparing to either run away or stand and fight. In people, the heart’s beating will speed up, breathing will quicken and the blood will send a boost of energy to the muscles.

In a 2015 study, his group showed that mice that ate a high-fat diet containing capsaicin did not gain extra weight. But a group of mice that ate only the high-fat diet became obese. Thyagarajan’s group hopes to start testing its new medication on people soon.

Other researchers have already tried similar therapies. Zhaoping Li is a doctor and nutrition specialist at the University of California in Los Angeles. In 2010, Li and her colleagues gave a pill containing a capsaicin-like chemical to obese volunteers. The chemical was called dihydrocapsiate (Di-HY-drow-KAP-see-ayt). It did help the people lose weight. But the change was slow. In the end, it also was too small to make much of a difference, Li believes. She suspects that using capsaicin would have had a bigger effect. Still, she argues, it would never work as a weight loss remedy. Why not? “When we convert the dose that worked on mice or rats to humans, [people] don’t tolerate it.” It’s too spicy! Even in pill form, she points out, capsaicin gives many people upset stomachs.

But Thyagarajan says his team has come up with a spice-proof way to get capsaicin into the body. A doctor would inject the drug directly into areas with a lot of fatty tissue. Magnets would coat each particle. The doctor would use a magnetic belt or wand to hold the particles in place. This should keep the capsaicin from circulating through the body. Thyagarajan believes that this would help prevent side effects.

Spice it up

Capsaicin may be the most exciting chemical inside a chili pepper, but it isn’t the only reason to spice up your diet. Both hot and sweet peppers also have important vitamins and minerals that the body needs. Li’s team is now studying how chilies and other cooking spices change the bacteria living in the human gut. Outside the body, spices help keep dangerous germs from growing on food. Li suspects that inside the body, they may rout bad germs. They might also help good bacteria thrive. She is investigating both ideas now.

A 2015 study even showed that people with spicy diets tend to live longer. Researchers at the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences in Beijing tracked half a million adults in China for seven years. Those who ate spicy food six or seven days a week were 14 percent less likely to die during those seven years than were people who ate spices less than once a week. And people who regularly ate fresh chilies, in particular, were less likely to die of cancer or heart disease. This result doesn’t necessarily mean that eating hot chilies prevents disease. It may be that people with healthy overall lifestyles tend to prefer spicier foods.

As scientists continue to uncover the secret powers of chili peppers, people will keep spicing up their soups, stews, stir-fries and other favorite dishes. Next time you see a jalapeño on a plate, take a deep breath, then take a bite.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

arthritis A disease that causes painful inflammation in the joints.

bacterium (plural bacteria)A single-celled organism. These dwell nearly everywhere on Earth, from the bottom of the sea to inside animals.

capsaicin The compound in spicy chili peppers that imparts a burning sensation on the tongue or skin.

chili pepper A small vegetable pod often used in cooking to make food hot and spicy.

curry Any dish from the cooking tradition of India that uses a blend of strong spices, including turmeric, cumin and chili powder.

dihydrocapsiate A chemical found in some peppers that is related to capsaicin, but does not cause a burning sensation.

fat A natural oily or greasy substance occurring in animal bodies, especially when deposited as a layer under the skin or around certain organs. Fat’s primary role is as an energy reserve. Fat is also a vital nutrient, though it can be harmful to one’s health if over consumed in excess amounts.

fight-or-flight response The body’s response to a threat, either real or imagined. During the fight-or-flight response, digestion shuts down as the body prepares to deal with the threat (fight) or to run away from it (flight).

gut Colloquial term for an organism’s stomach and/or intestines. It is where food is broken down and absorbed for use by the rest of the body.

hormone (in zoology and medicine) A chemical produced in a gland and then carried in the bloodstream to another part of the body. Hormones control many important body activities, such as growth. Hormones act by triggering or regulating chemical reactions in the body. (in botany) A chemical that serves as a signaling compound that tells cells of a plant when and how to develop, or when to grow old and die.

jalapeño A moderately spicy green chili pepper often used in Mexican cooking.

microbe Short for microorganism. A living thing that is too small to see with the unaided eye, including bacteria, some fungi and many other organisms such as amoebas. Most consist of a single cell.

mineral Crystal-forming substances that make up rock and that are needed by the body to make and feed tissues to maintain health.

nutrition The healthful components (nutrients) in the diet — such as proteins, fats, vitamins and minerals — that the body uses to grow and to fuel its processes.

obesity Extreme overweight. Obesity is associated with a wide range of health problems, including type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.

pepper spray A weapon used to stop an attacker without causing death or serious injury. The spray irritates a person’s eyes and throat and makes breathing difficult.

pharmacology The study of how chemicals work in the body, often as a way to design new drugs to treat disease. People who work in this field are known as pharmacologists.

proteins Compounds made from one or more long chains of amino acids. Proteins are an essential part of all living organisms. They form the basis of living cells, muscle and tissues; they also do the work inside of cells. The hemoglobin in blood and the antibodies that attempt to fight infections are among the better-known, stand-alone proteins.Medicines frequently work by latching onto proteins.

stress (in biology) A factor, such as unusual temperatures, moisture or pollution, that affects the health of a species or ecosystem.

tamale A dish from the cooking tradition of Mexico. It is spicy meat wrapped in cornmeal dough and served in a corn husk.

taste One of the basic ways the body senses its environment, especially our food, using receptors (taste buds) on the tongue (and some other organs).

TRPV1 A type of pain receptor on cells that detects signals about painful heat.

vitamin Any of a group of chemicals that are essential for normal growth and nutrition and are required in small quantities in the diet because they cannot be made by the body.

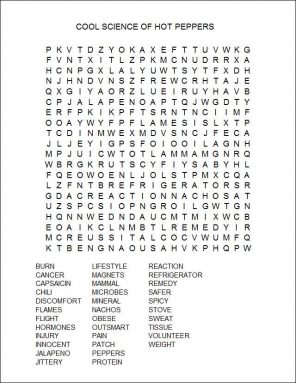

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)