Shading corals during midday heat can limit bleaching

During marine heat waves, a bit of shade can help corals hang on to their algal pals

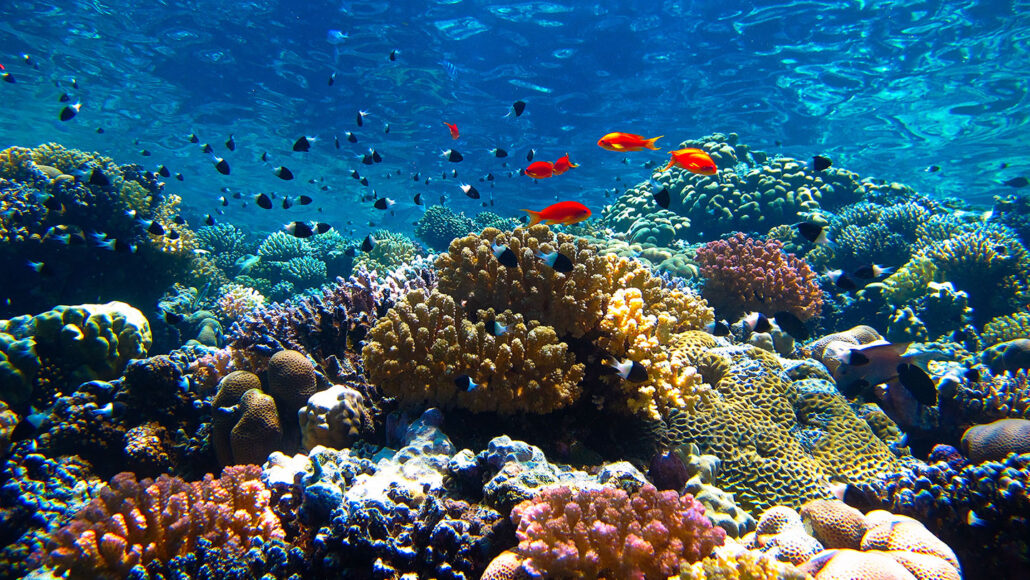

Shading coral reefs during marine heat waves can help corals keep the algae that give them their colors — and much of their food.

Johan Holmdahl/iStock/Getty Images Plus

This is another in our series of stories identifying new technologies and actions that can slow climate change, reduce its impacts or help communities cope with a rapidly changing world.

The world’s oceans hit record highs this year. And those soaring ocean temperatures aren’t just a problem for beachgoers. Too much heat poses a problem for coral reefs. Corals can bleach and eventually die if the waters around them get too warm. So scientists are searching for ways to help corals weather extreme heat. One new solution: shading corals during the sunniest part of the day.

Coral colonies are made of transparent polyps. These small, tube-shaped animals have a ring of tentacles surrounding their mouths. They like it warm, but not hot, and thrive with plenty of sun and fairly constant water temperatures.

“Healthy coral contains algae, which give the corals their amazing colors,” says marine biologist Peter Butcherine. He works at Southern Cross University in Coffs Harbour. It’s in New South Wales, Australia. Southern Cross is one of several universities that make up the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program.

Normally, corals and their single-celled algae have a mutually beneficial relationship. Corals give the algae a safe place to live. In return, algae make food via photosynthesis. They share this food with the polyps. Polyps also can catch tiny plankton. Most of their energy, however, comes from their algal partners.

Most corals live in shallow waters. As climate change has been raising ocean temps, some of these corals have ended up in water as warm as a hot tub. The sun they need can also get too intense. People can experience this, too. On a cool day, we may enjoy being in the sunshine. But when it gets hot, that sun is harder to handle.

“When algae are stressed, such as from getting too hot or too much light, they make harmful chemicals during photosynthesis,” Butcherine explains. Those chemicals can harm the coral. To protect themselves, the polyps boot the stressed algae out of their tissues. This causes the corals to lose their color, or bleach.

“Bleached corals are still alive,” Butcherine says. But if they don’t get more algae, he adds, “they may not get enough food.” Then they may die. So Butcherine’s team set out to try shading corals.

Throwing some shade

Previous research found that shading corals during a marine heat wave could help them keep their algae. But shading a huge reef isn’t easy. And too much shade could limit photosynthesis. Without enough light, both the algae and their corals could go hungry. So Butcherine’s group looked to shade them only during hours when the sunlight was most intense.

They collected samples of two different types of coral from the Great Barrier Reef off the coast of Australia. The corals were different shapes and sizes. They also contained different types of algae.

The team set up 76 pieces of each type of coral in individual outdoor aquariums. Half of each type was set up in water at 26.4° Celsius (79.5° Fahrenheit). That was the temperature where the corals had been collected. The other half were kept at 32.6 °C (90.7 °F). This mimicked a marine heat wave.

In each temperature group, the team varied the intensity of the light shining on the corals. One-third received full light. This represents what the corals would normally see. The team covered the other tanks with a shade cloth that blocked 30 percent of the light. Some tanks remained covered throughout the experiment. Others were only shaded for four hours, approximately 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. each day.

Then the researchers took photos to gauge bleaching. They also measured the density of algae and chlorophyll. That pigment is found in the part of the algal cell that carries out photosynthesis.

All corals housed in warmer water lost some algae and chlorophyll. But shaded corals lost less algae than those in full sun, even if that shade lasted just four hours. That protection faded over time, though.

After three weeks, even the shaded corals bleached.

“High water temperatures reduce the coral’s ability to repair and feed itself,” Butcherine reports. Shade helps slow the rate at which algae create harmful chemicals. But the longer the heat lasts, the harder it is for the corals to hold on to their algae.

High temps, he says, are “still the biggest threat to the coral.”

His team reported its findings September 20 in Frontiers in Marine Science.

Any side effects?

“Shading the ocean with artificial means could be a possible and relatively easy and cheap way to help protect marine life from the effects of climate change,” says Anny Cárdenas. She’s a biologist and coral researcher at American University in Washington, D.C.

“However,” she cautions, “it could also have some unintended consequences.” For instance, its effects on photosynthesis could alter the ocean food web.

Shading corals for just part of the day might protect algae while reducing potential negative impacts. The Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program is exploring ways to do this.

The goal, Butcherine says, is “to help coral reefs resist, adapt and recover from high ocean temperatures.” One idea they’re exploring is to develop machines that make fog from seawater. These artificial clouds could provide short-term shade to corals. This might be a safe way to reduce sunlight during those critical midday hours. And protecting corals could help a reef’s entire ecosystem.