Here’s how COVID-19 is changing classes this year

Schools are trying many tactics to keep students safe from the new coronavirus

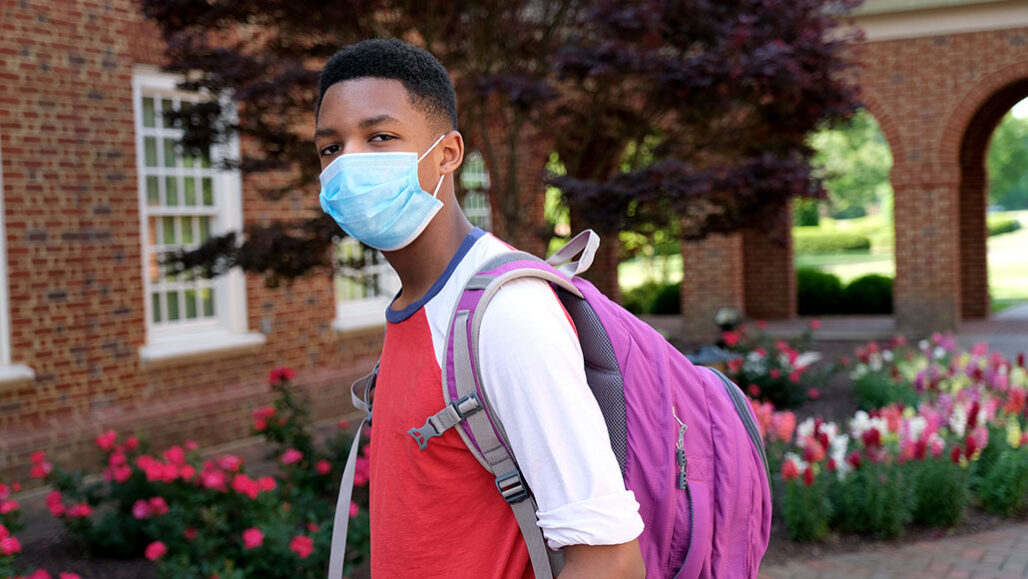

For kids going back to school, masks are just one thing that will be different. Some students won’t even walk into a classroom at all.

Imagesbybarbara/E+/Getty Images

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the world’s 1.5 billion students have been affected by school closures. With summer vacation over, classes are again resuming. But the 2020 school year will be different. With the COVID-19 pandemic still spreading, many people wonder whether it is safe for students and teachers to return to school.

Closing schools entirely isn’t a good idea. Without them, of course, students can miss out on learning math, science, language arts and more. But some also may miss out on breakfast and lunch. Some kids only get to see a doctor or nurse if they’re at school. Schools also teach valuable life skills, such as how to act around others. Kids and teens benefit from the friends they meet up with at school.

Because of that, many groups say it’s important now that students — especially kindergarteners to fifth-graders — return to school in person. Those groups include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Pediatrics.

But the decision to open a school to in-person learning isn’t a simple one. School systems around the United States are trying to figure out what is best for kids and their teachers. Some schools are continuing the virtual learning they launched last spring. Others are starting with virtual learning and hope to have kids walking the halls by late fall. Still other schools are letting students in, and parents can choose whether to send their kids and teens.

In every case, school will be different this year. Crowded hallways and cafeterias are things of the past. “I don’t think it would be safe, honestly,” says Beatrice Barilla, 13. Beatrice is starting eighth grade in the Montessori Middle School at W. G. Sanders Middle School in Columbia, S.C. “We can’t go in [the way we] would be normally. That would be a disaster.”

Staying home

In some U.S. communities, many people are infected with the new coronavirus. If some of them go to school and get close to others, the disease could spread. Keeping kids at home is a good way to slow the spread of COVID-19. So many schools will look different because they’ll be empty. Or they’ll be a lot less full because parents have chosen online learning for their children this fall.

Spencer Blosfield, 12, enjoyed virtual learning when COVID-19 hit. “I love to learn in the comfort of my own home, and I don’t want to leave,” he says. He loves computer science and finds it easy to code from home. Spencer will be starting seventh grade in a new school, Davidsen Middle School in Tampa, Fla. Florida is a state with a lot of coronavirus cases. Spencer’s not okay with going to school in person. “The pandemic is getting worse and then they’re sending people in person to school,” he says. “It’s killing a lot of people. It’s scary.” And so his parents have decided Spencer will continue virtual learning this fall.

But not everyone prefers virtual learning. Like many kids, Liza Granade, 13, switched to online school in March. They (Liza uses they/them pronouns) didn’t miss carrying all their books around Monrovia Middle School in Huntsville, Ala. But they also felt like they didn’t learn much. “It was really easy work,” Liza says. “Like, 30 minutes to an hour [per day].” There were no tests. And Liza is not sure they learned all they were supposed to. This fall, Liza will be starting eighth grade remotely again. “It’s not really going to change,” they say. “It’s going to be school, but I won’t get to see my friends.”

Keeping kids and teens home may be the safest option in a pandemic. But for some students — such as young children and those with special needs — virtual learning may not work at all.

Amanda Hecht is a special-education teacher in Massachusetts. Her kindergarten through fifth grade students are part of the Springfield public school system. Even one-on-one teaching over Zoom wasn’t great, she found. “I have no tools … like a counter or dice or fraction bars,” she says. “The social interaction is just not there,” she adds. “It’s not the same connection” and the students just “don’t have the same focus.”

In places where there isn’t a lot of coronavirus spread, it’s possible to do in-person classes safely, says Rainu Kaushal. She works at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. There, she studies how to make sure people get the healthcare they need in the best way. She recently investigated how other countries have managed in-person schooling during COVID-19. “Something like 20 countries have successfully reopened,” she says. “I think it can be done.” Kaushal published her analysis June 30 on a site called JAMA Health Forum.

The share of a community infected with COVID-19 should be what matters when sending kids to school, she says. “You don’t try to reopen in the middle of the epidemic.” So if your rates are going up, says Kaushal, “that’s not necessarily the time to reopen.” When COVID-19 cases pop up in a school, she says, it might just be time to shut down again.

Successful re-opening, therefore, will require that schools be flexible and make some changes.

Go with the (air)flow

Infected people can spread the coronavirus whenever words and air (and spit) leave their mouths. If healthy people nearby breathe in enough of those viruses in the air, they could get sick, too. Studies in labs have shown the virus can linger in the air for at least three hours.

There are ways to lower the risk, though. So it’s important to mix the air in the classroom with fresh air from outdoors, explains L. James Lo. His research at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Penn., focuses on how air flows through buildings. Mixing dilutes the indoor air, spreading out any virus it may hold. That, in turn, cuts the risk someone will encounter enough virus to make them sick.

Many heating and cooling systems in schools pull in air from outside and mix it with air already in the building. That’s usually good. It takes less energy to heat or cool some new air instead of all the air. Unfortunately, Lo says, in many schools, these systems don’t mix the air well enough to dilute any virus. That would take bringing in a lot more air, and pumping more of it per hour around the building. In most schools, Lo explains, that won’t be easy or affordable.

A small classroom might be able to install a small, portable air-cleaning unit. For a very large room, he adds, it’s probably is not doable.

Another option is to move classes outside. “Outdoor classes would be ideal. There’s precious little evidence of transmission outside,” says Ed Nardell. He’s a pulmonologist (Pull-mun-OL-uh-gist) — someone who studies the lungs and lung disease — at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass.

So this fall, classrooms might get new air filters that weren’t there before. Teachers might open windows and doors to help air move. And classes might be heading outside — as long as the weather is nice.

That’s what the Academy of the Holy Names in Tampa, Fla., has done. Carson Dobrin teaches high school chemistry there. Her school is offering both in-person and online classes. “We have top-of-the-line air filters,” she notes. There are also outdoor classrooms. “We’re going to try to do all eating outside unless it’s pouring,” she says. When kids do need to go indoors, she adds, the school has converted one big room into a giant lunchroom where everyone can eat six feet apart.

Keep your distance

Six feet is a good rule of thumb for reducing the risk of getting infected, and there are ways to make sure people stay that far apart. It’s hard to remember exactly how far six feet is, however. So where kids line up, schools may now put dots on the floor to mark off the distance. Desks also may be placed farther apart than before.

Another way to keep people apart is to put fewer kids in each classroom. “It allows you to do the appropriate social-distancing,” Kaushal explains. If one kid gets infected, only that small class may need to quarantine (stay home to stop COVID-19 from spreading). Other groups of students could still attend the school.

But shrinking class size is going to be extra hard, Dobrin points out. Splitting up classes requires more teachers. Adding to the challenge, many teachers are retiring or leaving because their families have had to move. “We’ve never lost this many people,” she says. With fewer teachers, “class sizes are bigger than we would like.”

Other teachers just don’t feel safe going back to class. Hecht, the special-education teacher, is worried about a COVID-19 outbreak once schools start. “My partner has cystic fibrosis,” she says. “So I’m worried about bringing [COVID-19] home and having him die.” Cystic fibrosis is a disease that causes sticky mucus to build up in the lungs. COVID-19 is particularly deadly for people with this disease.

For now, Hecht can teach from home. She is trying to make sure she won’t have to teach in person until there’s a vaccine to keep everyone safe.

Other simple behaviors could help everyone feel safer in classrooms, Liza says. These could include checking everyone’s temperature when arriving for the day. Schools also could require people to wash their hands and wear masks.

Masks can help lessen the spread of the coronavirus. “I feel like if everybody is wearing masks and in small groups and for less time and staying away from each other, that would be safe,” Beatrice says.

Masks are uncomfortable, though. They also can be hard for younger kids to wear. Teachers might need to give kids spaces to take off their masks for a while, Kaushal observes. Shorter school days might be needed, too, so kids can go home and take off their masks.

Many classrooms may have tall pieces of clear plastic between desks and in front of the teacher. Called sneeze guards or partitions, such barriers help limit someone’s exhaled virus from spreading to another. Even small droplets, Lo says, will stick to the barrier’s surface, preventing them from getting inhaled by others.

Some hallways might even become one-direction. That could make it confusing to get to class. But “the idea here is people are next to each other, not facing each other,” Lo explains. The less that people can breathe into each other’s faces, the better.

Among the hardest times to stay apart will be when kids ride a school bus. “Obviously, the safest form of transport would be if the child’s parents could bring them to the school,” notes Tina Tan. She’s a doctor for pediatric infectious diseases — ones that infect kids — at Northwestern University in Chicago, Ill. But many kids can’t get to school unless they ride a bus. Those kids will have to wear masks and won’t be able to sit together.

Squeaky clean

Scientists don’t think most COVID-19 infections come from virus left on things that people touch. The disease more likely spreads through shared air. But the coronavirus can stick to surfaces. So can other germs that make people sick.

People want to do everything they can to keep students and teachers safe. Schools already get cleaned a lot to make sure people don’t spread illness. Now, even more cleaning will necessary. Those partitions? They’re going to need to be kept clean. So will desks, hallways, books and any toys.

The entire classroom should be cleaned daily — desks, chairs, everything, says Kaushal. “I would err on the side of multiple cleanings a day.”

All this will require extra cleaning supplies. And these may cost more now, when cleaning supplies can be hard to find. Not all school districts may have the funds to supply classrooms with what they need. They may turn even more than usual to parents and teachers.

“My district usually does a very good job with cleaning supplies,” says Hecht. But she still sees teachers every year bringing in wipes, tissues and hand sanitizer. There’s never enough.

Another option is to cut off access to things that may be hard to clean. “A lot of schools are closing drinking fountains,” says Kaushal. “That’s a smart choice.”

Kids may need to bring in bottled water. They also will want to bring other supplies. To make sure that their germs stay with them, students shouldn’t share art supplies, pencils or paper, Kaushal says. Sharing is not always a good thing in the time of COVID-19.

Every effort schools take will help. Families can help too. In particular, Tan says, kids should get all their vaccines. There aren’t any yet for COVID-19. But there are for other diseases that can prevent school outbreaks — such as flu, chicken pox and measles. “If schools are seriously considering opening in person, they really need to ensure that their student population is up to date on their immunizations,” Tan says. “You don’t want to have an influenza outbreak on top of a COVID outbreak.”

Virtual learning, distancing, masks, cleaning — schools can’t rely on just one. Each tactic provides one more layer in our defense against COVID-19, Kaushal says. But even with all these measures at schools, kids still leave at the end of the day. If they become exposed outside of school, they could bring COVID-19 back to their teachers or classmates. So it’s extra important for kids and teens to stay home if they don’t feel well. No one wants to be responsible for spreading a disease to their teacher or friends.