Coronavirus most contagious before and right after symptoms emerge

Once the body makes antibodies, it stops churning out infectious virus

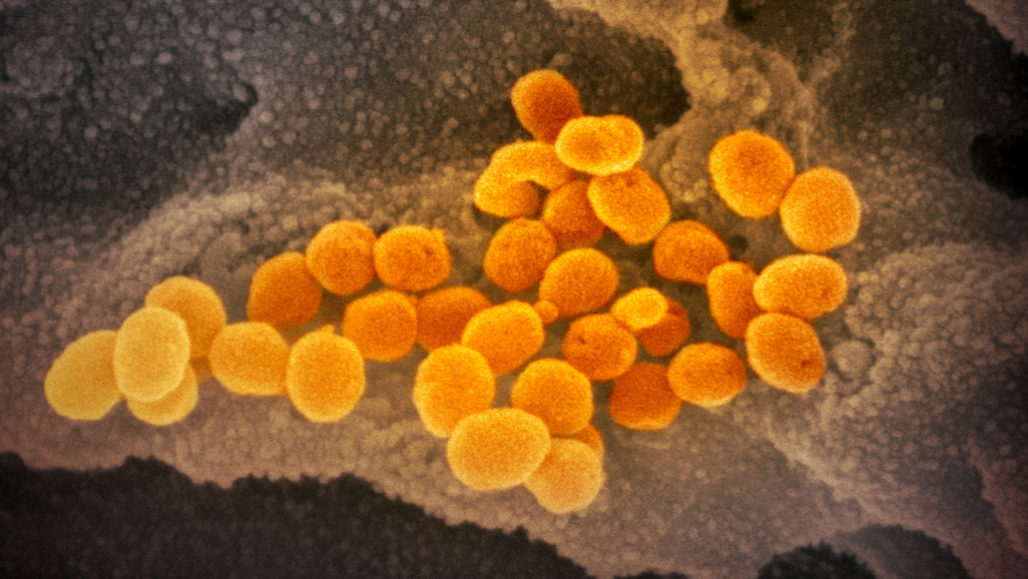

The coronavirus causing the global pandemic (orange) is shown emerging from a cell (gray). The virus can grow easily in the nose and throat — and may be shared before people know they are sick, a new study suggests.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-Rocky Mountain Laboratories/NIH

People infected with the novel coronavirus are mainly contagious before they have symptoms and for about a week after symptoms start. That’s the finding of a new study. It followed nine people in Germany who contracted COVID-19.

The new SARS-CoV-2 virus has triggered a global pandemic of COVID-19. The disease has been spreading within communities around the world. Scientists have been trying to figure out when infected people are most dangerous to be around.

Clemens Wendtner directs infectious disease and tropical medicine at Munich Clinic Schwabing, in Germany. His team isolated infectious viruses from about one in every six nose and throat swabs (17 percent) collected during the first week that people were infected. The team also found infectious viruses in more than eight in every 10 samples of phlegm (83 percent).

The researchers shared their findings March 8 in a study posted at medRxiv.org.

The patients in the study produced thousands to millions of viruses in their noses and throats. Indeed, Wendtner’s team found about 1,000 times as much virus in these patients as was produced in patients who had SARS (another potentially lethal coronavirus). That heavy load of viruses may help explain why the newer coronavirus is so infectious.

The German team identified the nine patients. Each had caught the virus from the same coworker. The scientists don’t know for sure exactly when each person began shedding the virus. Eventually, all but one patient showed COVID-19 symptoms. (These typically include a dry cough, fever and lung disease.)

After the eighth day of symptoms, the researchers could still detect genetic material from the virus — RNA — in swabs or phlegm samples. At this point, however, they no longer could find infectious viruses. That’s one sign that antibodies now being produced by the patients’ immune systems were killing viruses released by their body’s cells, Wendtner says.

All virus may not be infectious virus

Ali Khan is dean of the College of Public Health at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha and was not involved in the study. Finding RNA or pieces of a virus is no guarantee that the virus is “live,” or infectious, he concludes. That’s the good news. The bad? “When you are mildly [ill] or just [getting] sick, you’re putting out a whole lot of virus,” he says. And that, he adds, “explains why we’re seeing so much transmission within our communities.”

But there is some encouraging news. The new data suggest “that after about 10 days or so, you’re not likely to be infecting other people,” Khan says. Other studies, he says, also have suggested that people with very mild or symptom-free infections don’t shed much virus. They would therefore be less likely to infect others than people with more severe disease.

Wendtner’s group put the nine patients they studied through tests every morning during their hospital stay. The researchers collected blood, urine, stool, and nasal and throat swabs. They also asked each patient to cough up phlegm. “We were learning with the patients,” Wendtner says. At the time, “we did not know when would be the best and safest time to discharge them.”

The high levels of virus shedding from the nose and throat happened very early in the infections. This was when most patients’ upper airway virus production had already peaked. As the infection progressed, the findings suggest, the virus moved deeper into the lungs.

No evidence of the virus ever turned up in blood or urine. (So Wendtner’s group has stopped collecting those samples from a “second wave” of 23 patients that now are being treated at their hospital for COVID-19.) Viral RNA does show up in feces, but infectious virus does not. That suggests that the virus isn’t spread through poop.

All nine patients are employees of Webasto, an auto-parts supplier in Stockdorf. They caught the virus from a male coworker, who became known as Patient 1. Patient 1 got the virus from a business colleague from Shanghai, China. That person had visited Germany in January for meetings. Patient 1 and his Shanghai colleague transmitted the virus before either got symptoms. They are the first documented cases of symptom-free COVID-19 spread.

As health officials tested other employees of the company, they found the study participants. Each was then placed in isolation at the Munich clinic.

In one case, Patient 1 sneezed during a meeting with one of these people, Wendtner reports. “That was enough for infection.” In other cases, “they had simple business meetings, sitting together for 60 minutes, 90 minutes [at a table or] in front of a computer, with no physical contact,” Wendtner says — “just one handshake, that’s all.” So the virus is highly infectious.

Most patients developed coughs. Only two ever got a fever, the most common symptom in other studies. Most symptoms were mild. One person did develop severe pneumonia. Another showed no symptoms at all.

Two of the nine had runny noses. Previously, that symptom was rarely reported in COVID-19 patients. Another four had stuffy noses and reported that they couldn’t smell or taste anything, which annoyed them. “They could order anything they wanted [to eat], but [if] you can’t taste it, it doesn’t matter.” In the end, this cleared up in all of the patients, Wendtner says.

A temporary lack of smell or taste also affected some SARS patients in 2003, he notes. That symptom, he says, hints that in addition to causing swelling in the nose, the virus may infect nerve cells responsible for identifying odors.

All patients in the small study started making antibodies against the virus about six to 12 days after symptoms started. Once antibody production kicked in, researchers still found high levels of viral RNA in phlegm and in nose-and-throat swabs. At this point, however, no one was still giving off infectious virus.

The early and extreme contagiousness of the virus “tell us that gatherings of people should be avoided,” Wendtner says. But the results also may suggest that isolation periods could be shorter for people who have RNA but no virus. Researchers thought that because tests could sometimes still detect RNA for weeks after symptoms had cleared, patients were infectious for that long. Most patients, Wendtner notes, have not been released from the hospital until two separate tests within 24 hours come back negative.

But he doesn’t recommend letting people out of quarantine before their two weeks are up. “Fourteen days is safe and you have to keep it simple,” Wendtner says. “Maybe it’s safe 10 days after symptoms start, but you have to prove they have those neutralizing antibodies.” What’s more, tests for those antibodies are not widely available.

Beware viruses on surfaces, too

People aren’t the only direct source of infections. When people sick with the coronavirus sneeze, cough or touch something, they can leave infectious virus behind. A new study finds that those surface viruses can remain infectious for longer than you might think.

Neeltje van Doremalen is a postdoctoral research fellow at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Md. She was part of a team that has just measured how long the new coronavirus can “live” outside the body. It could last a day on cardboard and between two and three days on plastic or stainless steel. So that suggests that even packages left on doorsteps, plastic delivery bags and grocery goods in stores could host live virus for many hours — and potentially days. Live virus also lasted three hours or more in the air. So even walking through a room where someone had coughed may pose the risk of infection, these data suggest. The study by van Doremalen and her team has just been posted on medRxiv. — Janet Raloff