Could Zika become a cancer treatment?

This virus can kill brain cells that might otherwise morph into a deadly cancer

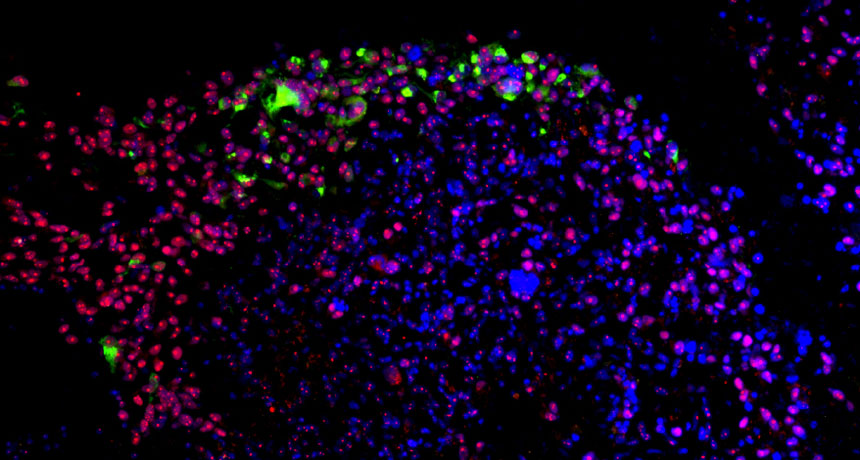

Zika virus (shown in green) infects and kills stem cells (red) in human glioblastoma tissue. It did not infect healthy brain cells. Because the stem cells generate the brain cancer cells, killing off the stem cells might prevent treated tumors from coming back.

Z. ZHU ET AL/JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE 2017

The Zika virus struck fear into the hearts of parents and would-be parents, last year. Moms who were infected during pregnancy often gave birth to babies with serious birth defects, including small brains. A number of the problems linked to the disease came from how the virus impacted the developing nervous system. But someday, Zika might also gain renown as a medical therapy — to treat deadly brain cancers.

That‘s the finding of a new study. In it, researchers infected human cells and mice with the virus. And in both, the virus killed certain stem cells — ones that would have gone on to become an aggressive type of brain tumor. This deadly cancer is known as a glioblastoma (GLEE-oh-blas-TOE-mah). Even more exciting, the germ left healthy brain cells unharmed.

Jeremy Rich is a scientist who focuses on regenerative medicine at the University of California, San Diego. His team shared its new findings online September 5 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.

Previous studies had shown that Zika kills the cells in the developing brain that can mature into nerve cells — also known as neurons. Neuroscientists thought maybe this explained the brain problems seen in many babies whose mothers who had been infected with Zika during pregnancy.

There are similarities between those cells that will become neurons and the cells that can turn into glioblastomas. Knowing this, Rich’s team suspected Zika might target the cells that can morph into the very deadly brain-cancer cells.

In the United States, some 12,000 people are expected to be diagnosed with glioblastoma this year. One of them was U.S. Senator John McCain. Doctors diagnosed his cancer this past July. The bad news: Even with treatment, most patients live only about a year after a gliobastoma diagnosis.

Rich and his colleagues have now tested their Zika treatment in the lab. They infected human stem cells that will go on to become glioblastomas. This treatment halted the cells’ growth, the scientists report. The virus also infected some full-blown glioblastoma cells, but not as many. The good news: The virus did not infect normal brain tissues.

Mice, too, can develop glioblastomas. And Rich’s team treated some mice with the cancer and then watched what happened to their disease. Compared to uninfected mice, tumors in the Zika-treated animals either shrank or grew more slowly. Zika-infected mice lived longer, too. In one trial, almost half of the mice survived more than six weeks with their brain cancer after being treated with Zika. In comparison, the cancers in mice who had not been uninfected with the virus died within two weeks of the start of the trial.

Using a virus to knock out cancer isn’t a new idea. Some tumors, including glioblastomas, are being treated with a modified poliovirus. Such trials are experimental. The U.S. government has also approved a modified herpes virus to treat melanoma, a deadly skin.

Andrew Zloza is a cancer specialist at the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey in New Brunswick. Cancer-fighting viruses seem to work in two ways, he says. First, they infect and kill tumor cells. Then, as the dying cells split open, previously hidden tumor fragments become visible to the immune system. The body recognizes those fragments and launches a fight against them.

“Right now we don’t know what kind of viruses are best” for fighting cancer, Zloza says. But Zika, he notes, is now another candidate.

Further tests are needed to find out if the virus is safe and effective in people. Since Zika’s effects are more harmful in developing brains, a Zika-based cancer therapy might be safe only in adults. And genes in the virus would need to be modified to make the germ safer and less likely to spread.

Rich and his colleagues are now running tests in mice to see if combining Zika with traditional cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy drugs, would be more effective than either treatment alone. Because Zika targets the cells that generate tumor cells, it might also prevent tumors from coming back.