Bringing COVID-19 vaccines to much of world is hard

As wealthy countries inoculate millions, vaccines still haven’t reached most poor nations

CHINHOYI, ZIMBABWE — A medical team crosses a flooded bridge in a rural Africa on its way to begin vaccinating health workers there on February 23, 2021.

Tafadzwa Ufumeli/Stringer/Getty Images News/Getty Images Europe

Months before the first COVID-19 vaccine was even approved, wealthy nations scrambled to line up hundreds of millions of advance doses. These would go to their citizens and no others. By the end of 2020, Canada had bought 266 million doses. That was enough to vaccinate all its people four times over. The United Kingdom snagged three times what its people needed. The United States, home to 330 million, reserved more than 1 billion doses and is now vaccinating more than a million people a day.

It’s a very different story in poorer nations. As of March 4, people in more than 80 countries have not yet gotten even one dose. Only 55 total doses were delivered to the 29 lowest-income countries; and all of them went to people in the West African nation of Guinea. Only a few countries in sub-Saharan Africa have begun regular COVID-19 vaccine programs.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus directs the World Health Organization. It’s based in Geneva, Switzerland. “The world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure,” he said on January 18. “And the price,” he added, “will be paid with the lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries.”

COVAX is an international COVID-19 vaccine program. It seeks to make access to the vaccines fairer. One way: It’s brokering deals that would send free shots to low-income countries. Despite new pledges of support from some of the richest nations, COVAX is off to a slow start. Its first shipment of 600,000 shots went out on February 24. Their destination: the nation of Ghana on Africa’s upper West Coast.

‘No one is safe until all of us are safe, since an outbreak anywhere can become an outbreak everywhere.’

— Gavin Yamey, Duke Univ.

Such stark differences in who can get vaccinated aren’t just an issue of fairness. A lopsided rate of global vaccinations risks prolonging the pandemic. At least as importantly, it could make it easier for the virus to evolve new vaccine-evading variants.

Gavin Yamey, is a global public-health-policy expert. He works at Duke University in Durham, N.C. Leaders in rich nations have done a very poor job explaining “why it’s so important that vaccines are distributed worldwide and not just within their own nation.” He argues that “no one is safe until all of us are safe, since an outbreak anywhere can become an outbreak everywhere.”

The reason: Viruses mutate.

Vaccine inequity could breed viral variants

Mutations are normal. They happen by chance as a virus copies itself inside a host.

Most mutations cause no harm. Or maybe no harm except to the virus itself. But every now and then, a tiny tweak to its genetic instructions makes a virus better at infecting hosts. Maybe they get better at evading our immune responses. The more a virus spreads, the better the chance that one (or more likely a handful) of these gene tweaks could birth a new, more threatening strain of virus.

In fact, this is has already begun.

In December, scientists detected a new variant in the United Kingdom. They dubbed it B.1.1.7. It had acquired mutations that made it more infectious. In just a few months, it’s turned up in more than 90 countries. This includes the United States.

Another variant first detected in South Africa also spreads more easily than the first version. Especially troubling, current vaccines don’t seem to work as well against this variant. It, too, has spread worldwide. Recent variants in California and New York are raising new concerns. As long as the virus is spreading widely, new variants will emerge.

No one yet knows “whether we’re going to have to continually chase this virus and develop more vaccines,” says William Moss. He’s the executive director of the International Vaccine Access Center. It’s at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, Md.

Variants could threaten even vaccinated people

The more the virus reproduces, Moss says, the more chance it has to evolve a way to resist vaccines or to the antibodies produced in response to earlier variants. Large pockets of unvaccinated people can become incubators for new variants. The longer such pockets persist, the greater the chance that variants will pick up changes that make them better able to resist vaccines. Eventually, such variants might invade well-vaccinated countries — ones that had thought themselves safe.

Barely vaccinated populations might be especially fertile incubators for these variants, says Abraar Karan. He’s a doctor of internal medicine at Harvard Medical School and Brigham Women’s Hospital in Boston, Mass.

Why? In someone who is vaccinated, mutations that even slightly evade the body’s immune response can get a toehold. They would not spread quickly in a well-vaccinated population. But if most of a region has never been infected with any form of the virus, that new variant could burn quickly through a group that is mostly unvaccinated. This could fuel the spread of this mutant virus to other parts of the world.

In Israel, more than 40 percent of the people have received at least one vaccine dose. Cases there have now fallen. But recently its health ministry has reported at least three cases of reinfection by the South African variant. These people had recovered earlier from COVID-19 and never been vaccinated. That’s a very small number of cases. Still it points to the threat posed when vaccination rates vary globally.

Says Karan, “If we want to stop the spread we have to stop it everywhere.” Otherwise, he worries, “We’re going to see continued outbreaks and suffering.”

Evening the playing field

COVAX is trying to even the vaccine playing field. But it has hit hurdles. For instance, it’s proving hard to line up scarce doses. It’s also been hard to make sure that countries have what they need to make sure they get into people’s arms. Succeeding could take equipping some countries with more ultracold refrigerators to store vaccines. Or it could mean converting mass vaccination programs for kids into ones that now jab the arms of adults.

Governments and charities give COVAX funds to buy vaccines and then send them at no cost to low-income countries. Three global public health powerhouses lead COVAX. One is the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization. Then there’s the World Health Organization. The last is the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.

COVAX plans to send 330 million doses to lower-income countries by June 2021. That should be just enough to vaccinate, on average, 3.3 percent of each of those nations’ populations. Meanwhile, many rich countries by that time will be well on their way to vaccinating most of their residents.

COVAX says it’s reserved 2.27 billion doses so far. That could vaccinate 20 percent of the populations in 92 low-income countries by the end of this year. But meeting this goal will require raising $8 billion dollars. On February 19, several countries pledged further support to COVAX, including $2 billion from the United States. Still, COVAX is billions short.

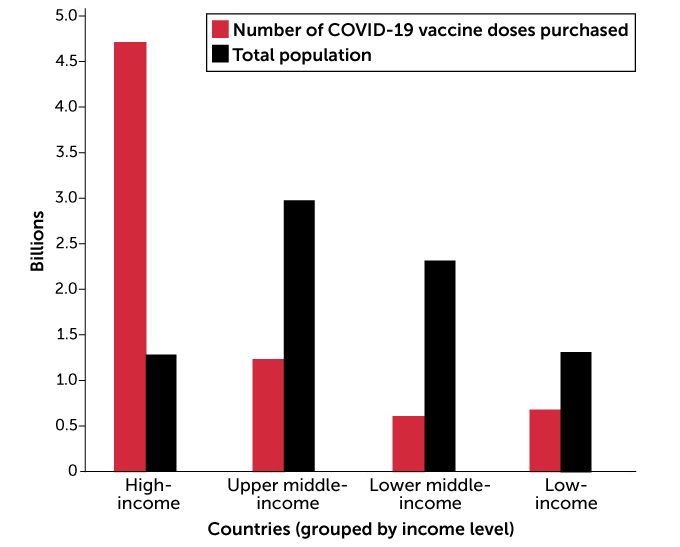

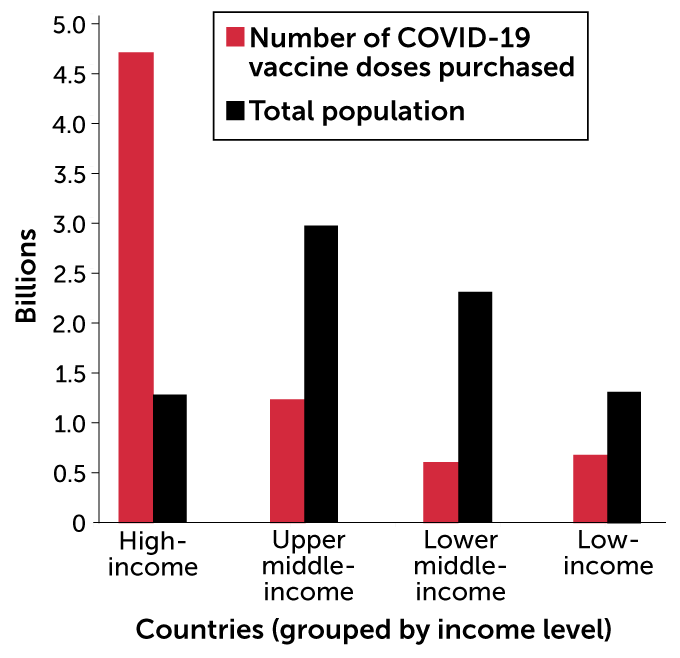

Unequal distribution

To date, high-income countries have purchased many more vaccine doses than less wealthy countries. Duke Global Health Innovation Center collated purchase data from countries in each World Bank income grouping, though not all countries in each income grouping were included in the analysis. The purchased doses are compared with the total population of countries included in each income grouping.

COVID-19 vaccine doses purchased by countries, grouped by income

“Money is not the only challenge,” added WHO’s Ghebreyesus in a February 22 news briefing. Deals between wealthy nations and vaccine makers threaten to gobble up global supplies. “If there are no vaccines [left for COVAX] to buy, money is irrelevant.”

People getting vaccinated anywhere is something to celebrate, says Yamey at Duke. “But it should disturb us to know that low-risk people are going to get vaccinated in rich countries well ahead of high-risk people in poor countries.” It would be fairer, he says, to put healthcare workers and vulnerable people in all countries at the head of the lines for vaccines. In fact, he notes, “I don’t see that happening.”

And even if COVAX could meet its goal for this year, low-income countries still will be far from reaching herd immunity. That’s the threshold at which enough people are immune to a pathogen to slow its spread. Estimates to reach herd immunity range from 60 to 90 percent of a population. And many low-income nations won’t get enough doses of the vaccine to have widespread vaccination “until 2023 or 2024,” Yamey notes.

“This inequity is due to hoarding of doses by rich nations.” Unfortunately, he adds, “that me-first, me-only approach ultimately goes against their long-term interests.”