Are coyotes moving into your neighborhood?

Learn how these cunning predators thrive alongside people

Coyotes thrive in cities. Seen in Denver, Colo., this one is lounging on a lawn in City Park.

tami1120/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Late one afternoon, Raphael Kaplan and his family were out walking near their home in Los Angeles, Calif., the second largest U.S. city. He looked through a fence surrounding a golf course and saw two coyotes.

They were “hanging out,” he says, “just lying down and waiting for us to pass.” This wasn’t an unusual experience for Raphael, who is 10 years old. The fourth grader says he sees coyotes all the time, often at that golf course. He’s also seen them walking down his street.

Coyotes look like medium-sized dogs or small wolves with short gray and brown fur. But they are a separate species, Canis latrans. They will eat just about anything and can learn to survive in nearly any environment.

Before 1700, coyotes only lived in the midwestern and southwestern United States and Mexico. But then people wiped out nearly all of North America’s wolves because the predators sometimes kill farm animals. This opened up space for coyotes.

People tried to get rid of coyotes, too. Some considered them to be pests. During the middle of the 20th century, the U.S. government poisoned around 6.5 million coyotes. Killing them is still legal in most U.S. states. Hunters and trappers kill hundreds of thousands every year. Despite all this, coyotes have survived and spread. They have moved into every U.S. state except Hawaii. Some roam only in wild areas. Many, however, make their homes in cities and suburbs. If you live in North America, chances are good that you have coyote neighbors.

Encounters with coyotes happen regularly across the United States as well as in Canada, Mexico and parts of Central America. In Chicago, Ill., for instance, coyotes once denned on the top floor of a parking garage across from Soldier Field, the home stadium of the Chicago Bears football team. In 2015, New York City police officers in trucks, cars and helicopters chased a coyote through Riverside Park in Manhattan. They aimed to move the animal out of the city. After three hours, they gave up the chase. The coyote had simply hidden itself too well.

Occasionally, coyotes may bite or attack people or their pets. However, coyotes mostly avoid people. Raphael is glad he’s gotten to see them so many times.

He’s also helped study them. From 2015 through 2019, the National Park Service’s L.A. Urban Coyote Project recruited kids and others without science training. These citizen scientists collected coyote poop and then sorted through it. The goal was to learn what city coyotes eat. Other studies in Los Angeles, New York City and Chicago have looked at where city coyotes go and how they behave. Such studies are teaching us how city coyotes thrive amongst people.

Scat party

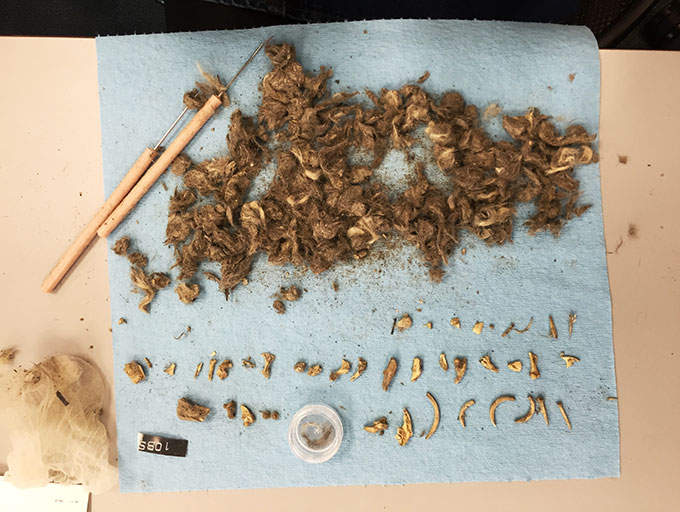

Raphael poked through a pile of coyote poop. “There were teeth, claws and whiskers,” he reports. “It was parts of rabbits.”

He was at a scat party organized by the National Park Service. (Scat is the technical name for wild animal poop). At tables spread out around a room, citizen scientists of all ages and all backgrounds inspected piles of scat. Justin Brown is a biologist at the National Park Service in Calabasas, Calif. He answered questions and helped identify everything. The group had found lots of rabbit remains. They also found lizard parts, rat teeth, beetles, fruit seeds, cat hair and much more.

Before the scat party, other volunteers had walked along planned routes, searching for coyote droppings. Some looked in a suburban neighborhood near the city. Others looked in downtown Los Angeles. Brown planned to compare the diets of coyotes from these two locations. When the volunteers found scat, they picked it up with gloves. Then they put it into paper bags, which they labeled with the date and location. Later, they’d drop these off with Brown and his team.

What did Brown’s team do with this smelly poop?

The first step was to roast the stuff in the oven for 24 hours at 60° Celsius (140° Fahrenheit). This killed any parasites or harmful microbes. “From there, we’d pour it out of the bags and look at each one,” says Brown. Sometimes, the volunteers collected dog poop by mistake. Coyote scat contains lots of hair from animals the coyote ate. The hair twists together at the end of each dropping. Brown and his team looked for this and several other telltale signs. They tossed out scat samples that probably weren’t from coyotes.

Next, they wrapped each sample in a stocking. They threw the stockings into a washing machine for a couple of cycles. This got rid of almost everything except hair, bones and other food leftovers. Finally, the stockings went into the dryer. By the time the stuff got to Raphael and the other scat party volunteers, it was clean and safe to handle. “It just smelled like dirt a little bit,” says Raphael.

During a series of such parties, volunteers and scientists worked together to identify the food sources in each sample. They had a lot to get through. “We ended up with about 3,000 scats,” says Brown. He noted that his team never would have been able to gather and process so much without community help.

Some interesting trends emerged from these comparisons of scat from city versus suburban coyotes. Suburban ones mostly ate rabbits. About 50 percent of those scat samples had rabbit remains. City coyotes also ate wild food. But their scat samples were more likely to contain garbage, pet food and fruit from trees people like to grow in their yards. Sometimes there were even the remains of pet cats. Some scats contained fast food wrappers. In fact, human-food sources accounted for as much as 60 to 75 percent of what urban coyotes ate.

Life in the big city

Do city coyotes have it made? Not exactly. Stanley Gehrt is a biologist at Ohio State University in Columbus. He has run the Urban Coyote Research Project in Chicago since 2000. Coyotes respond positively to some aspects of city life and negatively to others, he’s found. The more city-like an environment is, the harder it becomes for coyotes to succeed there.

One good part of city life is protection from hunting and trapping. These activities aren’t usually allowed within cities and suburbs. And cities offer an excellent supply of food, Brown’s research shows. That often includes wild prey.

“Downtown Chicago has an overabundance of rabbits,” says Gehrt. Before coyotes moved in, human trappers had to work to keep rabbit populations under control. Now, coyotes do that job.

Voles and squirrels are other coyote favorites. Squirrels have learned to visit people’s bird feeders, so some coyotes “crouch and hide near bird feeders,” waiting to pounce on a tasty squirrel, says Gehrt. Others munch on the berries and other fruits that people grow in their yards. Human food and garbage also is plentiful in a city.

Some coyotes get used to these easy food sources and lose their fear of people. If an animal begins approaching or bothering people, police or other local officials may kill it. To make sure coyote neighbors stay a safe distance away, people should secure their garbage, pick up fallen fruit and keep pet food inside.

Coyotes usually try to avoid people, but the more people there are, the harder that gets. Coyotes may end up with a very small home territory. It might be limited to a single park. They may cut across roads and highways to get to the different parts of their territory. Car accidents are the leading cause of death for urban coyotes.

But the more often coyotes cross roads, the better they get at it, notes Gehrt. He’s observed coyotes wait patiently at the edge of a highway. When they see a gap in traffic, they then run across as quickly as possible. He’s also watched coyotes using traffic lights. “They will wait until the traffic stops, then take their time, often using the crosswalk, to cross the road,” he says. “They know the traffic is going to stop.”

Urban coyotes also tend to spend more time hunting and traveling after dark. Fewer people are out and about then, so it’s easier and safer for them to get around.

Family matters

Coyotes have lived in the Los Angeles and Chicago areas since the early 1900s. So these animals have had more than a century to get used to city life. Coyotes moved into New York City only recently. The first sightings in this city of more than 8 million people took place in 1990.

“Most people don’t realize they’re here,” says Carol Henger. She’s a PhD student in biology at Fordham University who has studied New York City’s coyotes as part of the Gotham Coyote Project. To learn about the animals’ recent expansion into a new city, she studies their genes. Genes are made of DNA. They carry instructions on how the body should grow and behave.

Henger got those DNA samples from scat. Once again, citizen scientists stepped in to help. Ferdie Yau from the Bronx, N.Y., was one of them. He had studied wildlife biology in graduate school but decided to become a dog trainer. He realized he could use his skills to help the Gotham Coyote Project.

“I practiced with my own dog and was able to train her to find coyote scat,” he says. “She became really good at it.” His dog, Scout, was seven at the time. She retired from scat hunting last year at the age of 11. She’d sniffed out more than 100 scats, Yau guesses.

Henger and her team extracted DNA from all of the scat found by volunteers like Yau and Scout. They then tested to check whether each sample came from a coyote. If the DNA of several samples matched exactly, the researchers knew they came from the same individual. If several samples were very similar, those coyotes had to be part of the same family. “I was able to figure out that we had about five to six family groups in the city, all related to each other,” says Henger.

Most likely, all of these coyotes descended from the first few who ventured into the city. “They don’t seem to be getting in and out of the city to go find partners,” says Alexandra DeCandia. She’s a PhD student in genetics at Princeton University, in New Jersey, who also worked on the study.

This lack of movement in and out of the city isn’t good news for the coyotes. A healthy population of animals has high genetic diversity. That means that any two animals are likely to carry very different sets of genetic instructions. If something bad happens, such as a disease or a lack of food, there’s a higher likelihood that some of the animals will carry genes that will protect them or help them adapt.

New York’s coyotes “still have decent levels of genetic diversity,” says DeCandia. But if the population stays small and doesn’t get in and out of the city, genetic diversity will fall. This could eventually leave it at risk of diseases or other problems.

What prevents city coyotes from mixing with their rural neighbors? Highways act as barriers. But the coyotes also may not want to leave. Like the fable of the city mouse and the country mouse, a city coyote may feel very uncomfortable in the country, and vice versa, guesses Javier Monzon. He is a biologist at Pepperdine University in Malibu, Calif. “An animal born in the city, raised in the city and adapted to eating things in the city may not want to go [into the mountains],” he says.

In a genetic survey of the coyotes of Los Angeles and surrounding natural areas, he and his team found four distinct populations. One population lived in the mountains. These country coyotes were all more related to each other than to any of the city coyotes — even though some of the country coyotes lived on opposite sides of Los Angeles. Monzon and his colleagues shared their findings May 4 in the Journal of Urban Ecology.

Cities may not be the best home for coyotes. People get nervous when the dog-sized predators hunt and forage in their backyards. And coyotes may have trouble finding mates or avoiding cars. But despite these difficulties, city coyotes persist. We know from history that trying to get rid of them won’t work. Instead, today’s coyote experts focus on finding ways to help people and coyotes thrive safely, side by side.

Leave coyotes alone — they can be dangerous

Coyotes are wild animals. If you see one, don’t approach it or try to feed it. But don’t run away, either. “Yell at it. Wave your arms,” says Stanley Gehrt. “The coyote should run away.” If it doesn’t, you should report the animal to your local wildlife control agency.

On January 8, 2020, a coyote attacked a six-year-old boy in Lincoln Park in Chicago, Ill. The boy’s caretaker was able to scare the animal away and the boy survived. Such attacks on humans are very rare. This was the first in the city for decades. But young children especially should be very careful around these animals.

Pets that roam outdoors also could be in danger. Coyotes may hunt and eat cats or small dogs. Justin Brown’s study of coyote diet found that 20 percent of the scat samples from city-dwelling animals had cat hair in them. This was higher than Brown had expected. Still, pets are not a main food source.

Gehrt has been studying urban coyotes for 20 years. He says, “They’re not living off people’s pets at all.” In his studies of coyote diets, he’s rarely found remains of pets or signs of human food, pet food or garbage. Most coyotes — even ones that live in cities — prefer wild prey, he says.

It’s very unlikely that a coyote will attack you or your pet, but you should still be very careful around these wild animals.