Creating less new stuff could greatly help Earth’s climate

Here’s why scientists recommend moving to a cycle of reduce, reuse, repair and remake

Some designers salvage denim and other fabric from old clothes to create new, custom fashions. It’s one way to give new life to things that might otherwise be trashed. Another benefit: It avoids the environmental costs of using raw materials to make clothes.

Westend61/Westend61/Getty Images Plus

This is another in our series of stories identifying new technologies and actions that can slow climate change, reduce its impacts or help communities cope with a rapidly changing world.

Cows wandered in the distance as Rukayya Ibrahim Muazu and her colleagues set up a stand with information about plastic milk jugs. It was a sunny spring day in 2019 at Our Cow Molly farm in Sheffield, England.

Milk jugs and all the things we use daily have secret stories, Muazu knew. These are the stories of where the items came from before we got them and where they will go when we are done with them. At the time, Muazu worked at the University of Sheffield. A researcher with expertise in chemical and environmental engineering, she was studying such stories.

Take a plastic milk jug. To get it, drills must first pull crude oil from the Earth. Factories turn the oil into petroleum and then plastic. Other factories form the plastic into jugs. Trucks deliver those jugs to farms, where they get filled with milk.

Later, a truck will carry the full jugs to nearby stores and cafés, including one at Muazu’s school. After students like her stir all the milk into their tea or coffee, the café gets rid of the jugs. About half will get recycled. The rest head to landfills.

This process is quite typical today. Things get used up or break or we simply don’t want them anymore. So, we throw most of these into the trash. “There is so much waste,” says Muazu. Having completed her degree, she now works at the University of Surrey. It’s in Guildford, England.

Amelie Côté agrees. People “take, make, consume and throw away,” she says. She’s an analyst in Canada at Équiterre. It’s an organization in Montreal, Quebec, that seeks solutions to environmental problems. One of those problems is that too many people — especially those in the industrialized world — use and discard far more stuff than they should. This is called overconsumption.

Consuming too much stuff drains resources. It can harm ecosystems — even people, especially those in low-income countries. It also worsens climate change. According to the Global Footprint Network, last year people used 75 percent more resources than Earth can sustainably supply. Simply put, we’re asking Earth to give us more than nature can replenish. That sets up a problem: We have only one Earth from which to get those resources.

“Our patterns of consumption are in a large part driving the climate crisis,” says Sandra Goldmark. She’s an expert in sustainability at Barnard College and Columbia University’s Climate School in New York City. The pollutants that worsen climate change come from power plants, factories and vehicles. Most of these are running to supply people with stuff and services. In general, the more stuff we buy and use, the more pollution we emit.

The opposite of consuming too much is living sustainably. A sustainable product or process uses no more resources than the planet can supply now — and in the future. Living sustainably limits harm to the environment. When Earth had fewer people and no factories churning out cheap or disposable items, it could deal with our wasteful ways. But not anymore. Now that there are 8 billion of us, we need to learn to consume in a way that doesn’t destroy the planet.

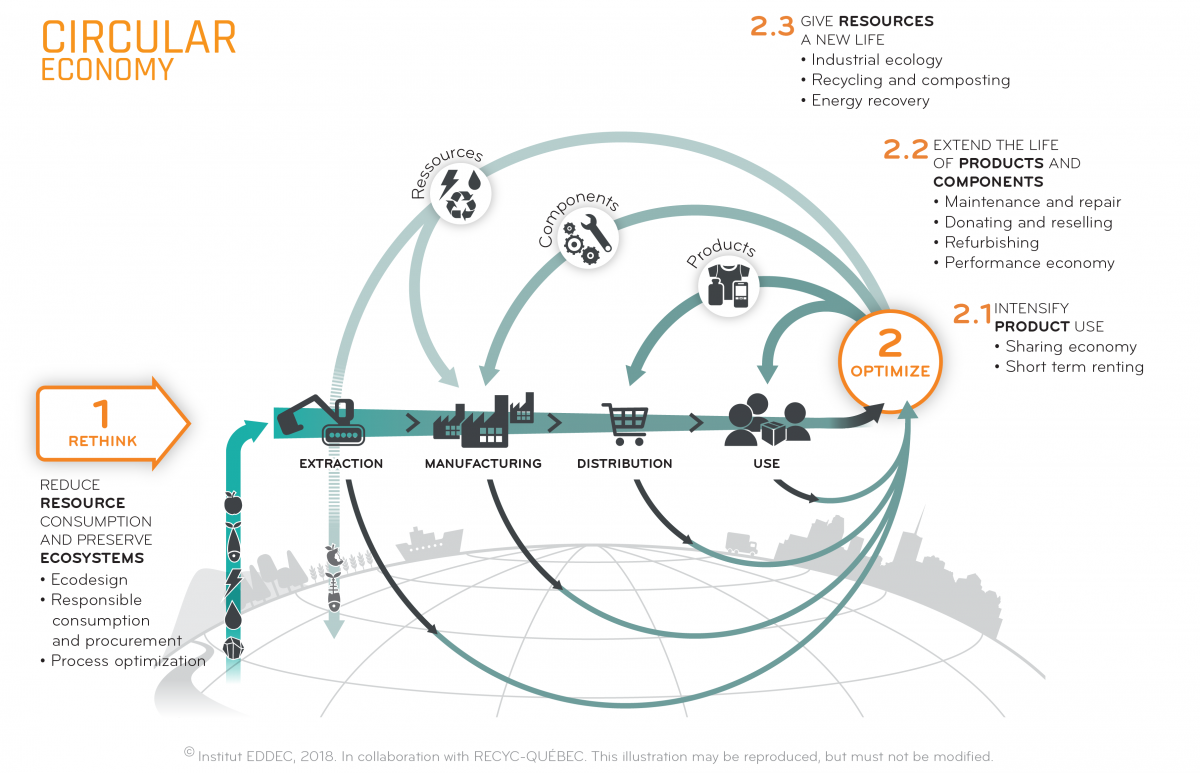

And that’s what experts like Muazu, Côté, Goldmark and others are working toward. Goldmark even wrote a book about it called Fixation: How to Have Stuff Without Breaking the Planet. Our goal, such experts say, is to turn the line of take-make-use-toss into a circle of reduce-reuse-repair-recycle-remake. They also call this a circular economy, where resources become goods, which become resources again.

To support this cycle, people must change the way they make and use things. “It takes a lot of energy to produce goods,” says Côté. “We want to make the most out of them.”

The life of stuff — from cradle to grave

Eddie Andrew is a farmer at Our Cow Molly. He had invited Muazu and her colleagues to visit after he got an idea. What if his farm replaced plastic jugs with glass bottles or large metal cans called churns? His workers could pick up empty containers, then wash and refill them. It seemed like it should be more sustainable, says Muazu. “One option uses a lot of plastic. The other uses less.”

However, confirming the advantage of moving away from plastic wasn’t as simple as it may sound. Producing one bulky metal or glass container uses up more resources and energy than producing one lightweight plastic jug. Also, reusable containers have to be washed with water and cleaning chemicals.

Reusing milk containers might “solve one problem while creating another,” Muazu says. Thankfully, engineers have a tool they can use to compare the different options. It’s called a life-cycle assessment, or LCA. It looks at the entire life of a product or process — from “cradle to grave.” LCA analyses will reveal something’s environmental impacts, often in ways that allow comparisons between products.

Many steps go into making the things you use every day. For example, a cotton T-shirt starts as fluff growing inside a boll on a cotton plant. “Cotton comes from the Earth,” explains Danielle Azoulay. She’s an expert in sustainability at Columbia University in New York City. Once cotton is picked, a factory turns it into lint. Another factory then spins those fibers into yarn. Next, the yarn gets woven into fabric and dyed. This all happens, Azoulay explains, “before it even gets to the factory to be made into a shirt.”

Finally, the shirt gets shipped to a store. Someone drives to the store to go shopping. Or they order online and have a truck bring the shirt to their house. Finally, someone gets to wear the shirt. When it gets dirty, they wash it. Eventually, they’ll throw the shirt away.

A metal milk jug can save 1,000 single-use plastic jugs from being made and tossed. Reusable metal water bottles and straws can also save energy and reduce waste — if you use them for long enough.

You must use a metal straw at least 100 times before the carbon footprint of making it and washing it is lower than the impact of 100 use-and-toss plastic straws.

Each step in this process impacts the environment. An LCA asks and answers questions about every single step. These include where it happened, how much electricity it used, what the source of that electricity was, how far vehicles had to travel, what other resources were used and so on.

One of the most common reasons to do such a life-cycle analysis is to calculate what’s called a carbon footprint. That’s a measure of how much a product or process impacts Earth’s climate over its lifetime. According to one 2020 estimate, more than 70 percent of the carbon footprint of a piece of clothing comes from making it. A much smaller portion comes from washing, wearing and disposing of it. Such LCA data helps people understand the harm of fast fashion. To lower the climate impact of fashion, people can keep and use clothing longer or buy more used clothing.

What about milk containers? Muazu’s team found that per liter (quart) of milk delivered, plastic jugs have a carbon footprint equivalent to 90 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). (Comparing things to CO2 is a way of using a single number to account for a mix of climate-altering pollutants). These jugs get used once. Afterward, only about half will get recycled. Metal churns, on the other hand, can be reused 1,000 times. Over their lifetime, they have a footprint of just 30 grams of CO2e per liter of milk.

The metal churns do use up more water overall than do the plastic jugs. But that tradeoff seemed worth it to Our Cow Molly. They now use metal churns to deliver milk to several local cafés.

Getting stuff fixed

Reuse is one important part of a more circular cycle for products. However, you can only keep reusing things as long as they still function. What if something breaks? Sadly, it’s often easier and cheaper to go online and order a new thing than to find a way to fix the old one.

In 2022, Côté and her team surveyed Canadians about their appliances and electronics. Almost two in every three — 63 percent — reported that at least one of their appliances or electronic devices had broken during the past two years. Yet only 19 percent — less than one third of these people — said they had gotten their broken product fixed.

Broken things typically end up in the trash.

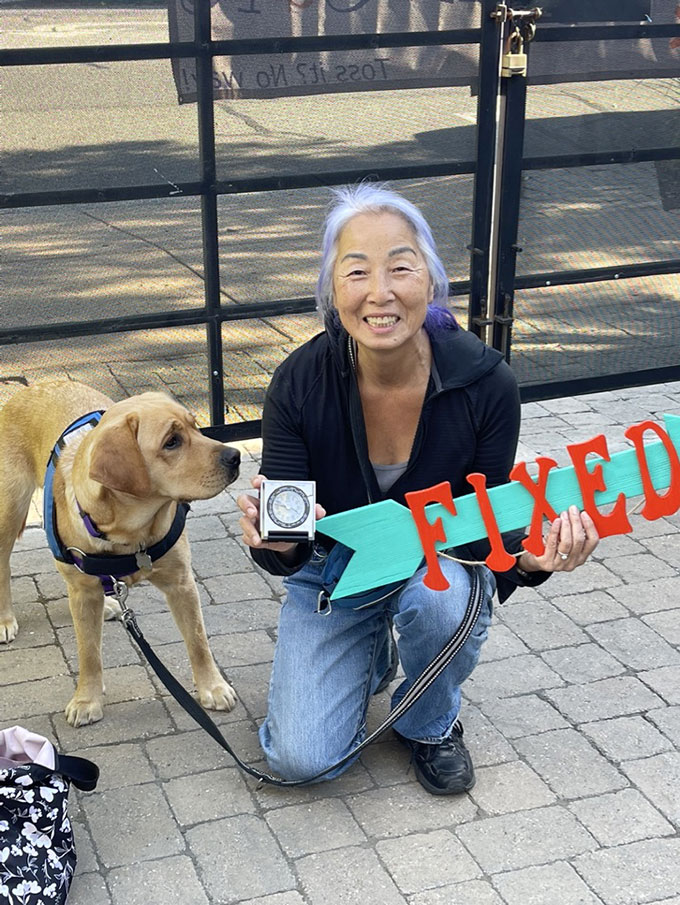

Back in 2013, Sandra Goldmark decided to do something about this problem. “So many things broke that seemed like they should be fixable,” she remembers thinking. She already had some repair skills. As a designer for a theater, she had made and repaired lots of costumes and scenery. So, she got together with some colleagues and opened a pop-up repair shop in New York City. They called it Fixup.

A pop-up shop stays open for a short period and then closes. The first one was such a success that the team spent the next seven years operating similar shops and events. They repaired more than 2,000 items. As a result, some 2,000 new things didn’t have to get made.

Sadly, many things couldn’t be fixed. Again and again, Goldmark and her team encountered flimsy plastic parts, pesky glue or screws that no ordinary screwdriver could undo. Côté found the same sorts of issues in her survey. Respondents thought their broken appliances and electronics were not repairable, she says. Also, the process to diagnose a problem, get the right parts and fix the item would take more time and money than people were willing to spend.

Flimsy or tough-to-fix products are not an accident. Many companies intentionally design things not to last. Why? They want you to have to buy a new one in the not-too-distant future. Another approach is to hype up a new item while making old items seem old-fashioned or obsolete. Both approaches are examples of “planned obsolescence.” Companies with these practices “want us on this treadmill where we buy more products from them regularly,” says Kyle Wiens.

Wiens is the founder of the website ifixit.com, based in San Luis Obispo, Calif. It provides manuals and instructions for repairing everything from iPhones to hospital ventilators. “We want to make it easier to fix things than to buy new things,” he says.

In October 2022, iFixit hosted a repair café in San Luis Obispo, Calif. Among the items people brought in for repair were this suitcase, seven pieces of clothing, 23 small appliances, six electronic devices and one bike.

Making stuff fixable

A “right to repair” movement is fighting to make repair an easier option for everyone. Ifixit.com scores items on how easy they are to repair. People can use these scores to choose among new items, finding ones that should last longer. In 2022, New York State enacted a new law — the first of its kind in the United States. It says companies must make available to the public repair manuals for their electronics — along with parts and tools.

This type of law isn’t bad for business, say Goldmark and Wiens. We can all adapt to a more circular way of using stuff. For example, companies can make money doing repairs. Or they can take back used items for resale to others.

Some companies are already taking these steps. Patagonia, which sells outdoor gear and clothing, offers repairs in its stores and through a mail-in program. In 2011, the company ran an ad on Black Friday — the most popular shopping day of the year. In big, bold, letters, it said: “Don’t buy this jacket.” According to the ad, the carbon emissions generated while making the jacket weighed 24 times more than the jacket itself. “We ask you to buy less and to reflect before you spend a dime on this jacket or anything else,” the ad said.

Caring about the environment is becoming trendy among companies. IKEA has committed to becoming a circular company by 2030. Target aims to do that by 2040. “I think there’s a lot to be hopeful about,” says Azoulay. She has worked with several major fashion and beauty companies to help them lessen their impacts on the environment.

Companies and customers should change their thinking when it comes to repair and reuse, she says. “New to me can still be exciting,” she says. When you buy a jacket that someone else has worn, she says, you could think about how many mountains it may have been to the top of. You can think, “I’m going to take this jacket on more adventures.”

Another interesting idea is to change how ownership works. Goldmark asks, what if people rented large items such as sofas instead of buying them? Then, when the item broke or the person was done with it, it would go back to the company that made it. If this were required by law, says Goldmark, companies would instantly start designing more durable products — ones they also could easily maintain, repair and resell.

A more sustainable world

The final stage of a more circular product cycle is what happens when things can’t be repaired or reused any longer. Ideally, the materials would be recycled and remade into new things. Sadly, most of what we put into recycling bins today never actually gets recycled. The process is just too costly.

When it comes to electronics, recycling also can be dangerous. That’s because circuit boards and batteries contain toxic and flammable materials. Yet failing to recycle electronics means trashing precious metals — including copper, platinum and gold.

Already, “the amount of gold that is essentially thrown away every year in electronics in the U.S. could be equivalent to the amount of gold that is mined in the country,” said Peng Peng. He’s a sustainability expert at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. He also coauthored a study about the importance of improving electronics recycling. It appeared in the January 2023 Nature Sustainability.

What if electronics and other items were designed from the start to be easy to take apart? That would make both repair and recycling much easier, says Wiens.

One farm changing the milk container it uses won’t stop climate change or save the planet. Neither will a few pop-up fix-it shops, or a few companies going circular.

We need a cultural shift, notes Goldmark. “We should spend money on people, not stuff,” she says. She means we should pay people fair wages to make products. People who clean, maintain, fix and recycle products deserve better pay as well. These types of changes will likely mean paying more for products than we do now. But the products themselves will last longer. So, we won’t need to buy as many. In the end, everything should even out. At least as importantly, the planet — including our climate — will be better off.

Companies and governments are the ones ultimately responsible for changing the way we make and use stuff. But every single person, including you, has a role to play. “You’re a really influential piece of the puzzle,” says Azoulay. Individuals can help by learning about sustainability and changing how they shop. It also helps to talk about these issues with friends, family and lawmakers. All of our small changes, when added together, could bend the harmful arrow of take-make-toss into a sustainable, long-lasting circle.