(for more about Power Words, click here)

algae Single-celled organisms, once considered plants (they aren’t). As aquatic organisms, they grow in water. Like green plants, they depend on sunlight to make their food.

coral Marine animals that often produce a hard and stony exoskeleton and tend to live on the exoskeletons of dead corals, called reefs.

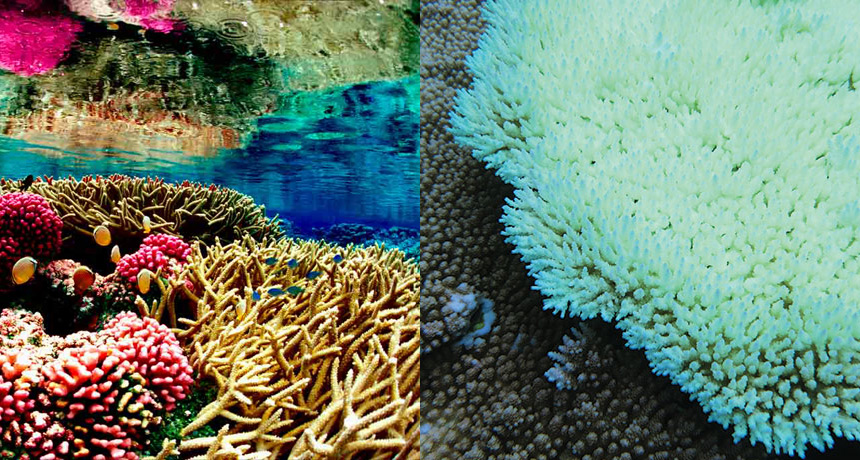

coral bleaching An event in which warming water or other stressors cause coral colonies to expel the algae that normally live inside them. Algae are a food source for coral (animals) and give them their vibrant colors. When algae are expelled, corals lose their color, turning a ghostly white.

ecosystem A group of interacting living organisms — including microorganisms, plants and animals — and their physical environment within a particular climate. Examples include tropical reefs, rainforests, alpine meadows and polar tundra.

El Niño Extended periods when the surface water around the equator in the eastern and central Pacific warms. Scientists declare the arrival of an El Niño when that water warms by at least 0.4 degree Celsius (0.72 degree Fahrenheit) above average for five or more months in a row. El Niños can bring heavy rainfall and flooding to the West Coast of South America. Meanwhile, Australia and Southeast Asia may face a drought and high risk of wildfires. In North America, scientists have linked the arrival of El Niños to unusual weather events — including ice storms, droughts and mudslides.

exoskeleton A hard, protective outer body covering of many animals that lack a true skeleton, such as an insect, crustacean or mollusk. The exoskeletons of insects and crustaceans are largely made of chitin.

global warming The gradual increase in the overall temperature of Earth’s atmosphere due to the greenhouse effect. This effect is caused by increased levels of carbon dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons and other gases in the air, many of them released by human activity.

model A simulation of a real-world event (usually using a computer) that has been developed to predict one or more likely outcomes.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA A science agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce. Initially established in 1807 under another name (The Survey of the Coast), this agency focuses on understanding and preserving ocean resources, including fisheries, protecting marine mammals (from seals to whales), studying the seafloor and probing the upper atmosphere.

reef A ridge of rock, coral or sand. It rises up from the seafloor and may come to just above or just under the water’s surface.

stress (in biology) A factor, such as unusual temperatures, moisture or pollution, that affects the health of a species or ecosystem. (in psychology) A mental, physical, emotional, or behavioral reaction to an event or circumstance, or stressor, that disturbs a person or animal’s usual state of being or places increased demands on a person or animal; psychological stress can be either positive or negative. (in physics) Pressure or tension exerted on a material object.

tissue Any of the distinct types of material, comprised of cells, which make up animals, plants or fungi. Cells within a tissue work as a unit to perform a particular function in living organisms. Different organs of the human body, for instance, often are made from many different types of tissues. And brain tissue will be very different from bone or heart tissue.

tropical Anything associated with the tropics, a region near the Earth’s equator where temperatures are generally warm to hot, year-round.