Death by asteroid may come in unexpected ways

Surprise: Winds and shock waves would claim the most lives

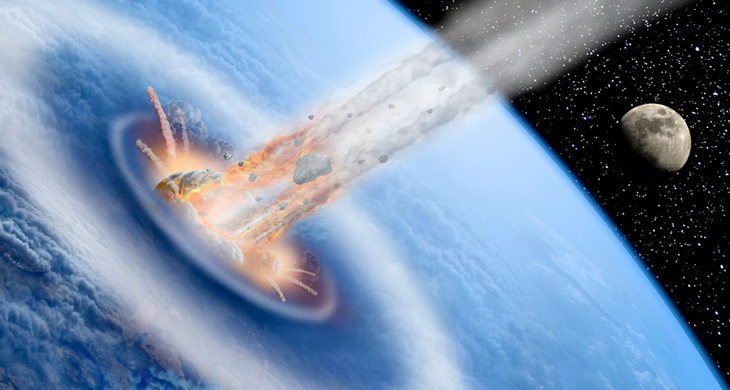

Here’s an artist’s rendering of a large asteroid breaking up as it begins to plow through Earth’s atmosphere. If it lands it could do a lot of damage, but how much would depend on its size and collision site.

ratpack223/iStockphoto

Every now and then a really big rock from space comes careening through Earth’s atmosphere. Depending on its size, angle of approach and where it lands, few people may notice — or millions could face a risk of imminent death.

Concern about these occasional, but potentially catastrophic, events keeps some astronomers scanning the skies. Using all types of technologies, they’re scouting for a killer asteroid, one that could snuff out life in a brief but dramatic cataclysm. They’re also looking for ways to potentially deter an incoming biggie from an earthboard path.

But if a big space rock were to make it to Earth’s surface, what could people expect? That’s a question planetary scientists have been asking themselves — and their computers. And some of their latest answers might surprise you.

For instance, it’s not likely a tsunami will take you out. Nor an earthquake. Few would need to even worry about being vaporized by the friction-heated space rock. No, gusting winds and shock waves set off by falling and exploding space rocks would claim the most lives. That’s one of the conclusions of a new computer model.

It investigated the likely outcomes of more than a million possible asteroid impacts. In one extreme case, a space rock 200 meters (660 feet) wide whizzes 20 kilometers (12 miles) per second into London, England. This smashup would kill more than 8.7 million people, computers estimate. And nearly three-quarters of those expected to die in that doomsday scenario would lose their lives to winds and shock waves.

Clemens Rumpf and his colleagues reported this online March 27 in Meteoritics & Planetary Science. Rumpf is a planetary scientist in England at the University of Southampton.

In a second report, Rumpf’s group looked at 1.2 million potential smashups. Here, the asteroids could be up to 400 meters (1,300 feet) across. Again, winds and shock waves were the big killers. They’d account for about six in every 10 deaths across the spectrum of asteroid sizes, the computer simulations showed.

Many previous studies had suggested tsunamis would be the top killer. But in these analyses, those killer waves claimed only around one in every five of the lives lost.

Even asteroids that explode before reaching Earth’s surface can generate high-speed wind gusts, shock waves of pressure in the atmosphere and intense heat. Space rocks big enough to survive the descent pose far greater risks. They can spawn earthquakes, tsunamis, flying debris — and, of course, gaping craters.

“These asteroids aren’t an everyday concern,” Rumpf observes. Yet clearly, he notes, the risks they pose “can be severe.” His team describes just how severe they could be in a paper posted online April 19 in Geophysical Research Letters.

Previous studies typically considered individually each possible effect of an asteroid impact. Rumpf’s group instead looked at them collectively. Quantifying the estimated hazard posed by each effect, says Steve Chesley, might one day help some leaders make one of the hardest calls imaginable — work to deflect an asteroid or just let it hit. Chesley is a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. (NASA stands for National Aeronautics and Space Administration.) Chesley was not involved with either of the new studies.

Land hits would pose the biggest risks

The 1.2 million simulated asteroid impacts each fell into one of 50,000 scenarios. They varied in location, speed and angle of strike. Each scenario was run for 24 different asteroids. Their diameters ranged from 15 to 400 meters (50 to 1,300 feet). About 71 percent of the Earth is covered by water, so the simulations let asteroids descend over water in nearly 36,000 of the scenarios (about 72 percent).

The researchers began with a map of human populations. Then they added in data on the likely energy that a falling asteroid would unleash at a given site. Existing casualty data from studies of extreme weather and nuclear blasts helped the scientists calculate death rates at different distances from a space rock’s point of impact. All that was then combined into the computer model to gauge how deadly each modeled impact would likely be.

The most deadly one would have killed around 117 million people. Many asteroid hits, however, would pose no threat, the simulations found. More than half of asteroids smaller than 60 meters (200 feet) across caused zero deaths. And no asteroids smaller than 18 meters (60 feet) across led to deaths. Rocks smaller than 56 meters (180 feet) wide didn’t even make it to Earth’s surface before exploding in the atmosphere. Those explosions could still be deadly, though. They would generate intense heat that could burn skin, the team found. They also would set off high-speed winds that would hurl debris and trigger pressure waves that could rupture internal organs.

Where asteroids fell into the ocean, tsunamis became the dominant killer. The giant waves accounted for between seven and eight of every 10 deaths from these asteroid splashdowns. Still, the casualties from water impacts were only a fraction as high as those due to asteroids that smashed into land. (That’s because asteroid-generated tsunamis are relatively small and quickly lose steam as they plow through the ocean, the computer model showed.)

Heat, wind and shock waves topped the impacts from land smashups, especially if they hit near large population centers.

Bottom line: For all asteroids big enough to hit Earth’s surface, heat, wind and shock waves caused the most casualties overall. Other land-based effects, such as earthquakes and blast debris, resulted in fewer than 2 percent of total deaths, the computer projected.

Protecting Earth

While asteroids have the potential to kill, deadly impacts are rare, Rumpf says. Most space rocks that bombard Earth are tiny. They burn up in the atmosphere, causing little harm.

Consider the rock that lit up the sky in 2013 and shattered windows around the Russian city of Chelyabinsk. Such 20-meter- (66-foot-) wide meteors strike Earth only about once a century. Far bigger impacts are capable of wiping out species. An asteroid at least 10 kilometers (6 miles) wide that smashed into Earth 66 million years ago has been blamed for wiping out the dinosaurs. Such mega-events are especially rare, however. They may occur only once every 100 million years or so.

Today, astronomers scan the skies with automated telescopes scouting for those potential killer space rocks. So far, they’ve cataloged 27 percent of those 140 meters (450 feet) or larger whizzing through our solar system.

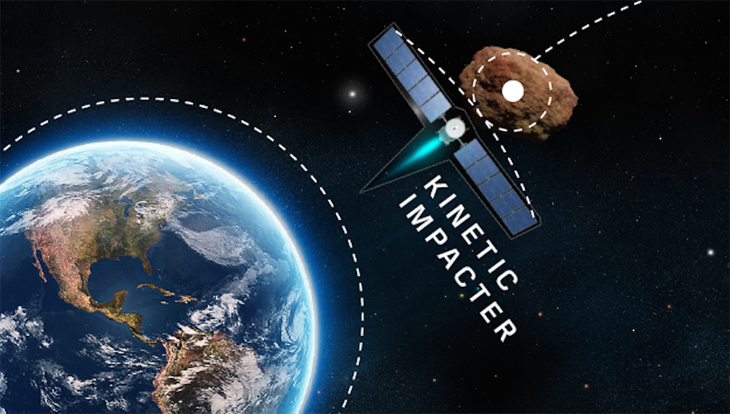

Other scientists are analyzing how they might divert or catch an earthbound asteroid. Proposals include whacking the asteroid like a billiard ball with a high-speed spacecraft. Or perhaps part of the asteroid’s surface might be fried with a nearby nuclear blast. The vaporized material should propel the asteroid away like a jet engine.

Understanding the potential threats — and options available to deal with them — could offer guidance on how people should react to a warning that an asteroid was heading Earth’s way. It might help people decide whether it’s better to evacuate or shelter in place — or even mobilize space troops to try and divert the asteroid.

“If the asteroid’s in a size range where the damage will be from shock waves or wind, you can easily shelter in place,” Chesley says. He says this should work for even a large population. But if the heat generated as it falls, impacts or explodes “becomes a bigger threat,” he says “and you run the risk of fires — then that changes the response of emergency planners.”

Making such tough calls will require more information about what the asteroids are made of, says Lindley Johnson. He serves as the “planetary defense” officer for NASA in Washington, D.C. Those properties in part determine an asteroid’s potential for bringing devastation. Rumpf’s team couldn’t consider how those characteristics might vary, Johnson says. But several asteroid-bound missions are planned to provide some answers to such questions.

For now, making decisions based on the average deaths presented in the new study could be misleading, warns Gareth Collins. He’s a planetary scientist at Imperial College London. A 60-meter- (200-foot-) wide incoming space rock, for instance, would cause an average of 6,300 deaths in the simulations. But just a handful of high-fatality events inflated that average. These included one scenario that resulted in more than 12 million casualties. In fact, most space rocks of that size struck away from population centers in the simulations. And they killed no one. “You have to put it in perspective,” he advises.

Death from the skies

A new project simulated 1.2 million asteroid strikes on Earth. That let scientists estimate how many deaths could result from each effect of a falling space rock. (Averages for three of the classes of asteroids that were evaluated are shown in the interactive below. People who could have died from two or more effects are included in multiple columns.)

Click the graphic to explore the asteroid simulation data.