Desert plants: The ultimate survivors

Desert shrubs, flowers and other plants have found amazing ways to survive heat, drought and poor soils

In spring 2005, wildflowers bloom after rare heavy rains at Death Valley National Park. Few places are hotter and drier than here, in the Mojave Desert. Still, more than 1,000 plants have evolved to survive its punishing conditions.

National Park Service

Three years into the worst drought on record, farmers in California have taken action to deal with the lack of water. Some farmers have drilled new wells deep below ground. Others are leaving fields fallow, waiting out the drought until there’s enough water again to sow their crops. Still other farmers have moved to greener, wetter locations.

When nature does not provide enough water, farmers use their brains, brawn and plenty of technology to find solutions. As clever as those solutions may seem, few are really all that new. Many desert plants rely on similar strategies to beat the drought — and have done so for thousands if not millions of years.

In the deserts of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, native plants have come up with amazing tricks to survive, and even thrive. Incredibly, these plants routinely cope with punishingly dry conditions. Here, plants can go a year without seeing a drop of rain.

Digging deep for water

The Sonoran Desert is located in Arizona, Calif., and northern Mexico. Daytime summer temperatures often top 40° Celsius (104° Fahrenheit). The desert cools off in winter. Temperatures at night can now fall below freezing. The desert is dry most of the year, with rainy seasons in summer and winter. Yet even when the rains come, the desert doesn’t get much water. So one way these plants have adapted is to grow very deep roots. Those roots tap into sources of ground water far below the soil’s surface.

Velvet mesquite (Prosopis velutina) is a common shrub in the Sonoran desert. Its roots can plunge down more than 50 meters (164 feet). That is taller than an 11-story building. This can help slake the thirst of a full-grown mesquite, a shrub related to beans. But seedlings must find a different solution as they begin to sprout.

Before a seed can take root, it must land in a good place to grow. Since seeds cannot walk, they rely on other methods to spread out. One way is to ride the winds. Mesquite takes a different approach.

Getting eaten helps the mesquite in a second way, too. The hard coating on its seeds also makes it difficult for water to get into them. And that is needed for a seeds to sprout. But when some animal eats a pod, digestive juices in its gut now break down the seeds’ coat. When those seeds finally get excreted in the animal’s feces they will at last be ready to grow.

Of course, to grow well, each mesquite seed still needs to land in a good spot. Mesquite usually grows best near streams or arroyos. Arroyos are dry creeks that fill with water for a short while after the rains. If an animal goes to the stream to have a drink and then does its business nearby, the mesquite seed is in luck. The animal’s feces also provide each seed with a little package of fertilizer for when it does start to grow.

Taking root

After an animal scatters mesquite seeds across the desert, the seeds don’t sprout right away. Instead, they lie in wait for rains — sometimes for decades. Once enough rain does fall, the seeds will sprout. Now, they face a race against the clock. Those seeds must quickly send down deep roots before the water dries up.

Steven R. Archer studies how this works. He is an ecologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. It’s in the heart of the Sonoran Desert. “I study ecological systems, which means the plants and the animals and the soils and the climate and how they all interact with each other,” he explains.

The Sonoran Desert doesn’t get long, sustained drenching rains, he notes. Most rain falls in short little bursts. Each might deliver just enough water to wet the top inch (2.5 centimeters) of soil. “But during certain times of the year,” Archer notes, “we get quite a few of those pulses of water.” A pulse is a short burst of rain. It might last anywhere from a few minutes to an hour.

Archer and his team wanted to see how two plant species respond to these pulses. The experts worked with velvet mesquite and a related shrub, cat’s claw acacia (Acacia greggii). In tests, the scientists doused seeds with varying amounts of water. They delivered it in varying numbers of pulses. Later, they measured how fast the seeds sprouted and grew roots.

Inside a greenhouse, the scientists planted seeds of velvet mesquite and cat’s claw acacia. They then soaked them with between 5.5 and 10 centimeters (2.2 and 3.9 inches) of water over 16 or 17 days. At the end of the experiment, the scientists measured the plants’ growth.

Mesquite seeds germinated quickly. They sprouted after 4.3 days, on average. Acacia seeds, by contrast, took 7.3 days. The mesquite also grew deeper roots. For the plants that got the most water, the mesquite roots grew to an average depth of 34.8 centimeters (13.7 inches), compared to just 29.5 centimeters for the acacia. In both species, the roots grew longer with each additional 1 centimeter of water the plants received. The acacia grew more above ground; the mesquite put most of its energy into growing a deep root as fast as possible.

Growing a deep root very fast helps ensure a mesquite’s survival. One study looked at a different type, honey mesquite (P. glandulosa). Most young plants of this species that survived their first two weeks after germination went on to survive for at least two years. That study was published January 27, 2014, in PLOS ONE.

Plant-friendly bacteria

Another common desert plant — the creosote bush — has adopted a different survival strategy. It doesn’t rely on deep roots at all. Still, the plant is a real desert survivor. The oldest creosote bush, a plant in California called the King Clone, is estimated to be 11,700 years old. It is so old that when it first germinated, humans were only just learning how to farm. It is much older than the pyramids of ancient Egypt.

Also known as Larrea tridentata, this plant is extremely common throughout large areas of the Sonoran and Mojave (moh-HAA-vee) deserts. (The Mojave lies to the north of the Sonoran, and covers portions of California, Arizona, Nevada and Utah.) The creosote bush’s small, oily leaves have a strong smell. Touching them will leave your hands sticky. Like mesquite, creosote produces seeds that can grow into new plants. But this plant also relies on a second way to keep its species going: It clones itself.

Cloning might sound like something from a Star Wars movie, but lots of plants can reproduce this way. A common example is the potato. A potato can be cut into pieces and planted. As long as each piece includes a dent called an “eye,” a new potato plant should grow. It will produce new potatoes that are genetically the same as the parent potato.

After a new creosote plant lives for about 90 years, it begins to clone itself. Unlike a potato, creosote bushes grow new branches from their crowns — the part of the plant where their roots meet the trunk. These new branches then develop their own roots. Those roots anchor the new branches 0.9 to 4.6 meters (3 to 15 feet) into the soil. Eventually, older parts of the plant die. The new growth, now anchored by its own roots, lives on.

David Crowley is an environmental microbiologist at the University of California, Riverside. He studies living things in the environment that are too small to see without a microscope. In 2012, he wanted to learn how the King Clone could have lived for so long with such shallow roots.

This plant “is located in an area where there’s often no rain for a whole year,” Crowley points out. “And yet this plant is sitting out there, surviving for 11,700 years in the most extreme conditions — sandy soil, no water, low nutrients available. It’s very hot.” His team wanted to scout for soil bacteria that might help promote plant growth.

Crowley and his team study how bacteria benefit plants. They developed a hypothesis that lots of different bacteria live near King Clone’s roots and that they help keep the ancient creosote bush alive.

To find out, the scientists dug around King Clone’s roots. The experts then identified bacteria living in this soil. They did this by studying the germs’ DNA. Most bacteria were types that help plants grow in different ways. Part of the plant’s health, Crowley now concludes, may trace to those “especially good microorganisms on its roots.”

Some of the bacteria produced plant-growth hormones. A hormone is a chemical that signals cells, telling them when and how to develop, grow and die. Other bacteria in the soil can fight the germs that make plants sick. The scientists also found bacteria that interfere with a plant’s response to stress.

Salty soil, extreme heat or a lack of water — all can stress a plant. When stressed, a plant may respond by sending itself a message that “it should stop growing. It should just hold on and try to survive,” Crowley notes.

Plants alert their tissues by producing ethylene (ETH-uh-leen) gas. Plants make this hormone in a strange way. First, a plant’s roots make a chemical called ACC (short for 1-aminocyclopropane-l-carboxylic acid). From the roots, ACC travels up a plant, where it will be converted into ethylene gas. But bacteria can interrupt that process by consuming the ACC. When that happens, the plant never gets its own message to stop growing.

If the stress got too bad — too little water, or very, very high temperatures — this nonstop growth would cause the plant to die. However, if the stress is small enough, then the plant survives just fine, Crowley’s team learned. It published its findings in the journal Microbial Ecology.

Gambling flowers

Mesquite and creosote are both perennials. That means these shrubs live for many years. Other desert plants, including many wildflowers, are annuals. These plants live a single year. That leaves them just one chance to produce seeds before they die.

Now imagine if every single one of those seeds germinated following a rainstorm. If a dry spell followed and all the little seedlings died, the plant would have failed to reproduce. Indeed, if that happened to every plant of its kind, its species would go extinct.

Luckily for some wildflowers, that’s not what happens, observes Jennifer Gremer. She’s an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey. Earlier, while Gremer worked at the University of Arizona in Tucson, she studied how wildflower seeds avoid making bad “choices.” Sometimes people who place bets use the same strategy. With plants, the strategy isn’t about winning money, however. It’s about the survival of its species.

Bettors sometimes hedge a bet. That’s a way to try and limit their risk. For example, if you had bet a friend $5 that the Kansas City Royals would win the 2014 World Series, you would have lost all of your money. To hedge your bet, you could have bet another friend $2 that the Royals would lose the World Series. That way, when the Royals did lose, you lost $5 but won $2. That may still have hurt, but probably not as badly as if you had lost all $5.

Imagine that a desert wildflower produces 1,000 seeds that all fall to the ground. The first year, only 200 of the seeds germinate. That’s the bet. The other 800 seeds are its hedge. They just lie and wait.

If that first year is very rainy, the 200 seeds might have a good shot at growing into flowers. Each in turn can produce more seeds. If the year is very dry, however, many, if not most, of the seeds that germinated will die. None of these seeds, then, got to reproduce. But thanks to the hedge, the plant gets a second chance. It still has 800 more seeds in the soil, each able to grow next year, the year after that or maybe a decade later. Whenever the rains come.

Hedging has its risks. Birds and other desert animals like to eat seeds. So if a seed sits on the desert floor for many years before growing, it might get eaten.

The wildflower ‘hedge’

Gremer and her team wanted to know how 12 common desert annuals hedged their bets. The experts tallied what share of the seeds germinated each year. They also counted what share of ungerminated seeds survived in the soil. (For example, some seeds end up getting eaten by animals.)

As luck would have it, another ecologist at the University of Arizona, Lawrence Venable, had been collecting data on wildflower seeds for 30 years. He and Gremer used these data for a new study.

She suspected that if a species of desert flower is very good at surviving, most of its seeds would germinate each year. And her suspicions proved correct.

She used math to anticipate how many seeds of each plant would germinate each year if the plant were using the best possible strategy for survival. Then she compared her guesses to what the plants really did. By this method, she confirmed the plants had been hedging their bets after all. Some species did better than others. She and Venable described their findings in the March 2014 issue of Ecology Letters.

Filaree (Erodium texanum) hedged its bets only a little. This plant produces “big, yummy seeds” that animals like to eat, Gremer explains. It also is better than many other desert annuals at surviving without much water. Each year, about 70 percent of all filaree seeds germinate. After all, if the tasty seeds remained in the soil, animals might eat most of them. Instead, when the seeds sprout, they have a good chance of surviving and reproducing. That is this plant’s hedge.

A lack of water makes it hard for plants to grow. That’s something crop farmers in California have seen only too well over the last three years of drought. In the deserts of the Southwestern United States, drought is a permanent feature of life — yet there, many plants still thrive. These plants succeed because they have evolved different ways to germinate, grow and reproduce.

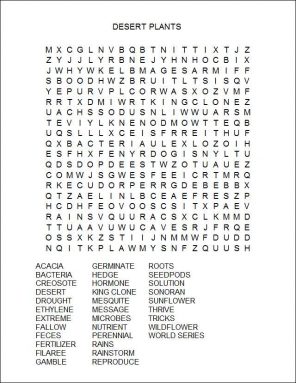

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)