Dinosaur ‘mummies’ may not be as rare as once thought

Their skin can be preserved and fossilized even when not buried right away

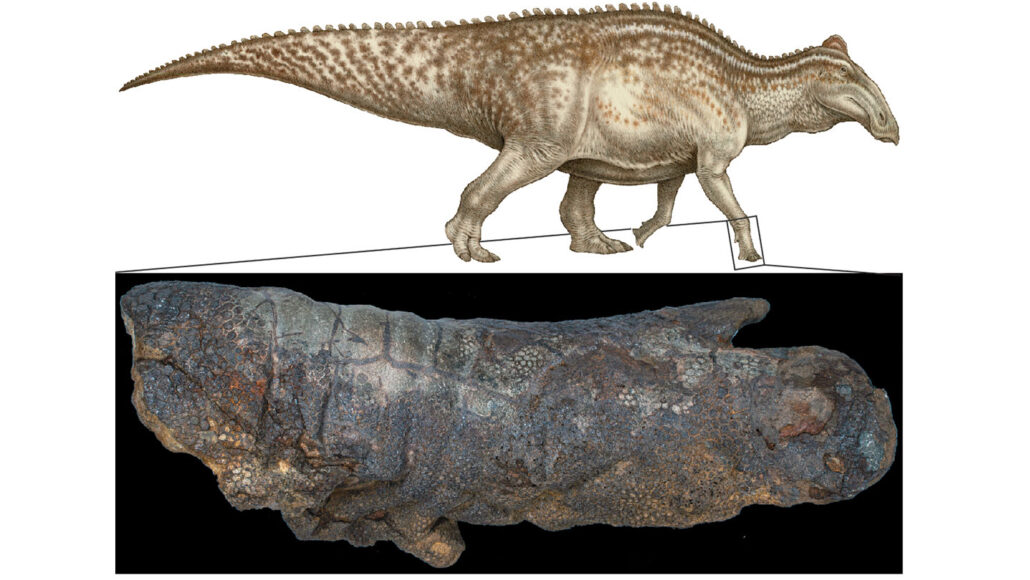

In life, Dakota was a duck-billed dinosaur (illustrated at top) that would have spanned the length of a full-size school bus. Large sections of its body, such as its right front foot, include fossilized scaly skin (bottom) that extends down to its hoof-like nail.

Natee Puttapipat, CC-BY 4.0

By Jake Buehler

It might be easier for dinosaurs to “mummify” than scientists had thought.

Scientists turned up unhealed bite marks on one dino’s fossilized skin. They think this shows the carcass had been partially eaten before being buried by debris. The team shared its finding October 12 in PLOS ONE. Until now, most scientists thought a mummy could only form when a body had become buried right after death.

The new research centers on one fossil, named Dakota. It lived some 67 million years ago. Dakota was unearthed in North Dakota in 1999 and belonged to a group of duck-billed dinosaurs known as Edmontosaurus. The mighty plant eater was roughly 12 meters (39 feet) long. Today, Dakota’s fossilized limbs and tail still contain large areas of well-preserved, fossilized, scaly skin. It’s a striking example of dinosaur “mummification.”

The creature isn’t a true mummy because its skin is no longer skin. It has turned into rock. Most animal fossils only include the hard body parts, such as bones. Researchers call fossils with exquisitely preserved skin and other soft tissues “mummies.”

In 2018, a group of paleontologists found what looked like tears in the tail skin and puncture holes on Dakota’s right front foot. The team included Clint Boyd of the North Dakota Geological Survey, in Bismarck. His group teamed up with Stephanie Drumheller. She’s a paleontologist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Together they removed extra rocky material around the fossil. That allowed them to investigate what caused the skin marks.

The holes in the skin are a close match for bite wounds from prehistoric relatives of modern-day crocodiles, they now report. No one had ever seen something like this in a dinosaur fossil, Drumheller says.

The marks on the tail are larger than ones on the front limb. That’s why the team thinks there were at least two different carnivores munching on Dakota’s carcass. They were probably scavengers. But scavenging doesn’t fit into the long-accepted view of how skin fossilizes.

“This assumption of rapid burial has been baked into the explanation for mummies for a while,” Drumheller says. But that doesn’t seem to be what happened to Dakota. This dino had probably been dead for a while if scavengers had enough time to snack on its carcass.

Drumheller noticed that Dakota’s skin had shrunk to surround the underlying bone. Here, the muscle and organs were gone. That’s when this paleontologist made an unexpected connection. “I had seen something like this before,” she says. But it was from forensics research, not paleontology.

Most modern scavengers, such as raccoons, would rip open a carcass to feed on its internal organs. Forensic scientists showed that such a hole gives any gases and fluids an escape route. That allows the remaining skin to dry out. Burial could happen later.

How rare were these conditions?

These scientists “make a very good point,” says Raymond Rogers of Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minn. His work focuses on how organisms decay and fossilize. It’s very unlikely for a carcass to both dry out completely and get buried rapidly, he says. Both of these are believed to be important for making mummies. They are also somewhat incompatible, he adds.

Fossilization of soft tissues — such as skin, brains or fleshy head combs — is uncommon, but not unheard of. It’s more common than you would expect if they can only fossilize through very a specific sequence of events, Drumheller says. Perhaps, then, mummies originating from more common series of events could explain this.

Dry, “jerkylike” skin could last long enough to be buried and fossilized. But the conditions needed may not happen often, says Evan Thomas Saitta. He’s a paleontologist at the University of Chicago, in Illinois.

“I still suspect that this actual process is a very precise sequence of events,” he says. And, he adds, that means “if you get the timing wrong, you end up without a mummy dinosaur.”

Understanding that sequence of events, and how common it is, requires figuring out how fossilization proceeds after a mummy’s burial. This is something Boyd says he’s interested in studying next.

“Is it just the same fossilization process as for the bones?” he asks. “Or do we also need a different set of geochemical conditions to then fossilize the skin?”