DNA takes notes

Engineers develop a computer memory system based on living cells

Every electronic gadget needs a good memory. A music player saves songs, albums and playlists. A computer holds schoolwork and programs — and remembers how far a player advanced in her favorite game. Mobile phones recall names, numbers and hundreds of texts.

Now, scientists in California say they’ve come up with a way to turn a living cell into a memory device.

It can store only a tiny bit of information, but it’s a start. In the future, a cell-based gadget might travel through the body and record measurements. The benefit to human health could be big: The right tool, for example, might record the earliest signs of disease.

Doctors, scientists and other curious people want to know what’s happening inside the body, even at levels invisible to the naked eye. So far, there’s no device small enough to travel through the bloodstream. (And, unlike the characters in the 1966 sci-fi movie Fantastic Voyage, we don’t have a ray that can shrink a submarine small enough to cruise through the body.)

If normal machines won’t do the trick, perhaps biology will. Scientists who work in the field of synthetic biology try to find ways to turn living things into human tools. In the case of the new memory device, bioengineers from Stanford University used the genetic material inside living cells to record information.

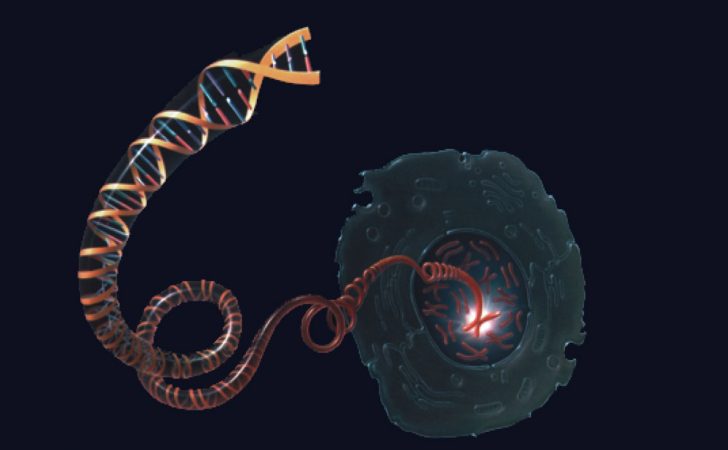

Resembling a jumble of thread, this genetic material consists of a long and coiled molecule called DNA. Found in nearly every cell, DNA carries all of the information that keeps a living thing alive.

In the new experiment, the researchers turned DNA from bacteria into a switch. They used an enzyme, or a substance that makes things happen inside a cell, to flip a small section of DNA so that it was backward. Then, using the same procedure, the scientists flipped the section again — returning it to its normal structure.

This idea is similar to how computers work. Computer memory depends on billions of tiny electrical switches, usually made from silicon, that are either “on” or “off.” The “flipped” or “unflipped” state of the DNA-based memory device would be similar to the silicon’s switches being on or off.

Using these DNA switches, “We can write and erase DNA in a living cell,” bioengineer Jerome Bonnet explained to Science News

It might take years before his team or others identify whether a DNA-based memory device might be practical. Right now, it takes one hour to finish a flip. That’s way too long to be useful. Plus, one flipped section holds very little memory — less than what a computer uses to remember a single letter.

“This was an important proof of concept that it was doable,” Bonnet told Science News. “Now we want to build a more complex system, something other people can use.”

Power Words

synthetic biology An area of science that focuses on developing new and useful tools from living materials, or using synthetic materials to build things that behave like living organisms.

silicon A nonmetal chemical element used in making electronic circuits.

cell The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism, typically too small to see with human eyes.

nucleus A part of a cell that contains the genetic material.

chromosome A threadlike structure of nucleic acids and protein found in the nucleus of most living cells, carrying genetic information in the form of DNA.