Do school-shooter drills hurt students more than they help?

Being prepared is essential, but there’s little research on what works best

Schools often invite police officers in to make students more comfortable with them in case of an emergency. Now many schools have added drills that make children practice lockdowns or strategies to run, hide or fight.

SDI Productions/E+/Getty Images

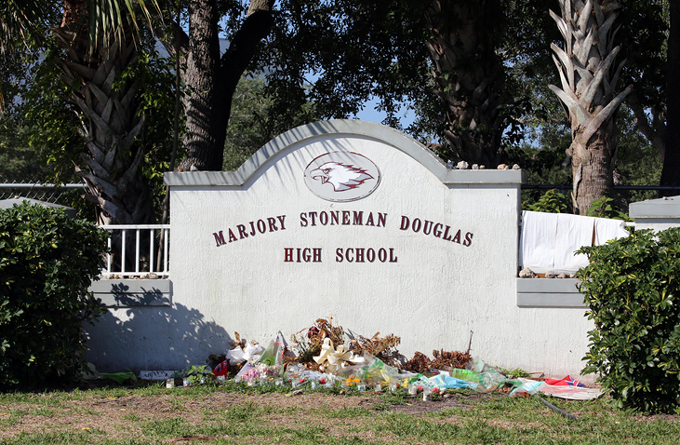

“My plan always was to go out the window of whatever classroom I was in,” says Aalayah Eastmond. Her elementary school had shooter drills. Her high school held drills during her freshman and sophomore years. Another drill was planned for February of her junior year. Then on February 14, 2018, a gunman entered Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla. And all those plans went out the window.

“When you’re actually in the shooting, you don’t have time for that,” Aalayah recalls. “That’s not how it happens.” Within minutes, gunshots killed 17 students and staff members. Classmate Helena Ramsay had been passing back textbooks. Teens were supposed to use them as shields for their heads. Nick Dworet’s body covered Aalayah as she waited for the violence to end.

Six years earlier, a teen gunman opened fire in the cafeteria at Chardon High School in Ohio. Some students fled to a teacher’s lounge and blocked the door with a piano. Others stayed inside their classrooms. A football coach chased the shooter from the building. By then, six students had been shot. Three of them died. Another was paralyzed from the waist down.

The tragedy could have been worse, says educator April Siegel-Green. At the time, she headed up student services for the school district. “Prior to the shooting, we had started to develop safety plans,” she explains. “And we had a variety of different types of drills.” She believes the high school’s active-shooter drill “absolutely saved lives.”

More than 240 shootings have happened at U.S. schools since two teen gunmen killed 13 people in 1999 at Columbine High School in Colorado. Those shootings have touched more than 233,000 children and teens, according to a Washington Post tally. Yet school shootings remain quite rare.

“The odds of a student aged five to 18 being a victim of a homicide at school are one in 2.8 million,” says school psychologist Stephen Brock. He works at California State University, Sacramento. You’re much more likely to get hit by lightning. The U.S. National Weather Service puts your lifetime odds for that at one in 15,300. And the National Safety Council says the lifetime odds of dying in a car crash in the United States are one in 103.

Even a tiny chance of a shooting worries educators, however. More than 4 million U.S. students were in at least one lockdown during the 2017-2018 school year. That’s what the Washington Post reported in December 2018. Lockdowns can happen when there’s a threat aimed at a school or somewhere in its vicinity. Schools also want to be prepared before any threat emerges. That’s why about 19 in every 20 U.S. public schools have drills to prepare for possible shooters, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Researchers are just beginning to look at the impacts of all those drills. A few studies suggest that certain types of training might minimize the chance of shooting deaths. However, there are no clear standards on how drills should be run.

And those studies that examined drill impacts are not conclusive. Those drills can have emotional impacts on kids. But it’s not clear what those impacts always are and who is most likely to suffer from them. Much depends on the type of drill and the students’ personal situations, psychologists say. And to date, no studies show that drills actually prevent school shootings.

Being prepared

Aalayah didn’t take the possibility of a shooting seriously until she learned that a gunman shot and killed 26 first graders and educators at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn. “I thought if it could happen to them — little innocent children — it could definitely happen to me at any time and place,” she recalls.

Seven-year old Josephine Gay and six-year-old Emilie Parker were killed in that 2012 tragedy. Soon afterward, the girls’ moms founded Safe and Sound Schools. The group supports the idea of safety drills to deal with a wide range of hazards. But the drills need to be appropriate for children’s different stages of development, says Josephine’s mom, Michele Gay. And the drills should avoid scaring or possibly causing their own trauma.

“Obviously, the point is to empower people,” the former teacher says. “But the last thing we should be doing is frightening people.” She says, “We’re not focusing on some bad guy dressed up. We’re not focusing on scary sounds or smells or anything sensorial. We’re literally just talking about how we recognize when we’re in a [threat] situation, and what are the actions.”

Safe and Sound Schools recommends that schools assess their own threat risks and shape plans to their communities. Plans should be tailored to the age and maturity of the kids involved. First graders might learn that different situations call for different responses. If there’s a fire, you leave immediately. If there might be an intruder outside, you find a safe corner in a locked classroom and stay quiet. By high school, you might help with quickly locking and blocking doors.

“When people are faced with an emergency situation, we know that they might not be able to think clearly,” Gay explains. “We want all of that to be ‘pre-loaded.’ That’s why we rehearse the steps of safety.”

“Preparedness is essential,” says Amanda Nickerson. She’s a psychologist at the University at Buffalo in New York. “I think we’re beyond the point of saying let’s not do these drills anymore.” However, there are relatively few studies that point to which drills work best.

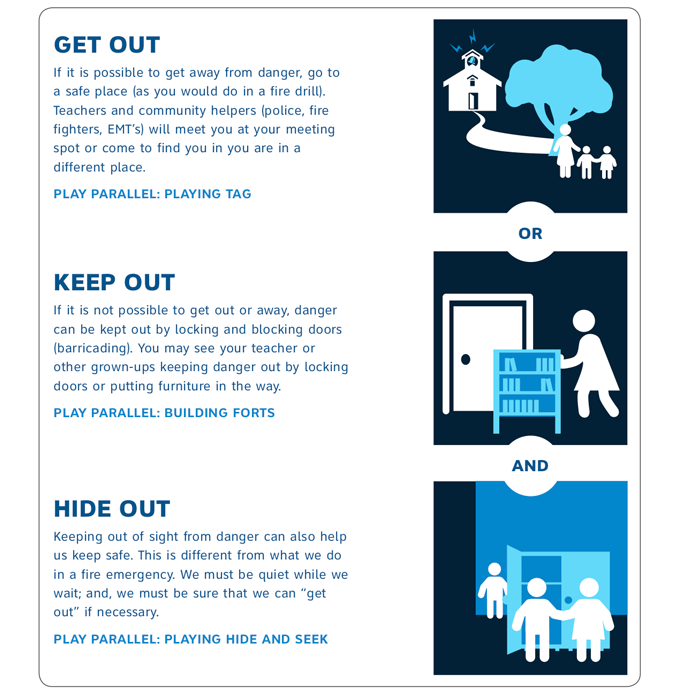

Cheryl Lero Jonson is a criminologist at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She and her colleagues recently studied how adults performed in two situations. One was a “traditional lockdown.” People locked doors and stayed put. The other was a program taught by the ALICE Training Institute, based in Medina, Ohio. Depending on the situation, participants had to choose whether to get away, to block entry to a shelter spot and hide, or to fight to counter an attack.

For each of several cases, a shooter tried to enter a classroom and shoot plastic pellets at as many people as possible. When people could only hide, the classroom attacks lasted from 22 seconds to almost five minutes. On average, almost three in every four people got shot in those cases. When people had choices, the average time for the classroom attacks was 16 seconds, and an average of just one in every four inside got shot. Jonson’s team concluded that shootings would end sooner and have fewer injuries if drills offered choices. The study appeared in the December 2018 Journal of School Violence.

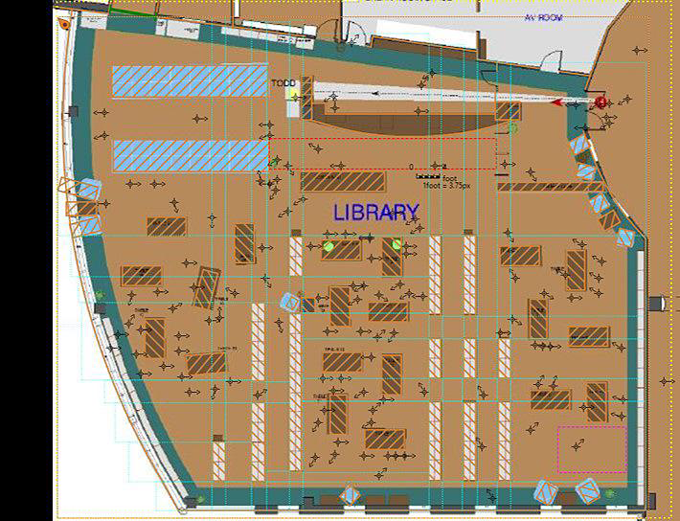

Another recent study skipped the guns and used a computer model. Researchers at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., based their model on the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado. In that attack, two teens killed 13 people and then themselves. The computer model tested cases in which everyone hid, everyone ran or everyone fought. It also tested a case in which one third ran, another third hid and the rest fought the attackers.

The model’s results showed that everyone would have been shot if they all hid. There would have been 21 victims if everyone ran. And it calculated that there would have been five victims if everyone fought. The best result was the combo scenario, with three victims.

Eric Dietz worked on the model at Purdue. The choices to run, hide or fight aren’t equally good, this computer scientist stresses. “It isn’t run or hide or fight. It’s run if you can. Hide only to get back to running again when you can. And if you can’t run or hide any more, then you’d better fight, because you’ve got no other options left.” He and others hope to minimize casualties if a shooting does take place. But, he adds, “We want to make sure we have some science to back up why we tell students to take certain actions.”

Kenneth Trump heads National School Safety and Security Services. It’s a company in Cleveland, Ohio. He sees a big risk for bias in the study by Jonson’s group. Why? One of its authors works for the ALICE Institute, which makes money doing shooter drills and training. Jonson and the other co-author were certified trainers for the ALICE program. Plus, the study participants were already going through training at the ALICE Institute, and only a few were educators. (Jonson did say that her team took some steps to reduce bias. The “shooter” was not with the ALICE program, and instructions were very specific, for example. Yet the group studied was not a random sample.)

More generally, Trump says, options-based training for students “fails to consider age and developmental factors.” It also fails to consider other variables, such as children who might have special needs (such as being deaf or needing a wheelchair). Students may give shooters more targets if they run. And a majority of school shooters have not been subdued by citizens. Some school employees also have been injured in options-based shooter drills, he adds. In contrast, lockdowns focus on securing classrooms and avoiding more risky situations. In his view, “lockdowns work and are the gold standard in best practices for more than two decades.”

And even the scenarios with fewer victims still had some casualties. Aalayah says she hadn’t minded doing shooter drills because she likes to be prepared. “But afterward, I realized how stupid they are,” she says, “because it doesn’t save you in a real situation.”

Avoiding harm

Julia Susany, now 19, had done different types of shooter drills since first grade. She feels it helped to be prepared. Still, young students didn’t really understand why they did the drills. After the Sandy Hook shooting, that changed. “It wasn’t reassuring once I realized what we were doing,” she says. “It became more creepy.” And it felt like schools were treating shootings as something almost normal. Nonetheless, she says, “I was glad I had at least something to fall back on in case there was an emergency.”

Julia’s high school in Akron, Ohio, taught drills with options to get away, hide or fight. However, the teachers stopped short of having students actually throw things at a role-playing gunman. After all, someone could get hurt.

Several students did get bumps and bruises during a December 2019 drill in New Richmond, Ohio. The principal had acted as a shooter. The students were trying to get away. The school used the same type of program as Julia’s high school.

Some experts also worry that drills could cause emotional harm. In a 2007 study, Nickerson and a colleague looked at the short-term effects of an intruder drill. Two groups of 4th-, 5th- and 6th-grade students learned about the steps. Then they practiced the drill. Teachers locked classroom doors and shut off the lights. Students moved into corners. Everyone tried to stay quiet.

Afterward, the team gave a five-question quiz to those students and two other groups that didn’t do the drills. The groups that practiced had more knowledge about what to do for a drill. And their anxiety levels were not much different from those in kids from the other groups. The team concluded that similar drills could increase children’s short-term knowledge and give them useful skills to use in a real crisis.

“We didn’t do long-term follow-up in our study,” Nickerson notes. “And I know of no research that has.” Her study also didn’t look at more intense drills, such as run-hide-fight programs. It’s highly unlikely that students would ever come face-to-face with an active threat. Plus, a drill that could cause mental trauma would “raise ethical concerns,” the study noted.

“Getting behind a locked door saves lives,” says school psychologist Melissa Reeves. She studies school-crisis prevention at Winthrop University in Rock Hill, S.C. Typical lockdown drills can be done calmly without raising anxiety levels in most students, she says. “We can’t promise that nothing bad is ever going to happen. But when we give students things to do, it brings a sense of control. And it brings us safety and security.”

While options-based programs can be done calmly, some school drills have been far more intense than Reeves or others would recommend. Students have cowered as alarms blared and masked “gunmen” shot blanks or starter guns. Some schools have had students play shooting victims. Teens at one charter high school in Colorado even practiced how to take down a mock gunman.

“We don’t light a fire in the hallway to practice fire drills,” Reeves says. “And we do not have to shoot off a safety gun or have screaming to simulate what it’s like to be in an active-shooter situation.” And while a drill might not be stressful for most students, it could stress some. “If your school is asking you to participate in a highly sensorial drill,” she says, “you have a right to say no if you are uncomfortable.”

Schools also should give students and parents some warning about when drills will happen. “There should never, ever be an unannounced, highly sensorial drill,” Reeves says. “There should never be an unannounced lockdown drill.” Indeed, unannounced drills have caused some kids to run from schools. Panicky 911 calls followed.

If done well, a lockdown drill can lower anxiety and teach students good, adaptive behaviors for when a bad situation arises, Brock says. And the options of evacuating or hiding also can serve other, less scary purposes. For instance, such procedures might deal with something like a strange dog on the premises.

However, Brock recommends against having armed-assailant or active-shooter drills for elementary-school students. And he’s wary about using them with students in middle school and high school. If a student has a history of trauma or is already anxious, depressed or stressed, “these drills are going to be upsetting.” Some students might have had friends or family members who were victims of gun violence.

Others may have mental-health problems, often undiagnosed or untreated. “One in five students in this country is dealing with a mental-health challenge of some sort,” he says. Of those, “only 20 percent are getting care and treatment.” Brock encourages students to talk with school counselors, parents, teachers or other trusted adults if they feel stressed or anxious.

When Chardon High School resumed drills after the 2012 shooting, there were no real gunshots, Siegel-Green says. Parents could choose to keep students home. Counselors were on hand to talk with students. Comfort dogs were also available for at least one drill after the shooting. However, not all schools offer that type of follow-up. Julia says students at her school generally knew they could see a counselor if they felt stressed. Still, it wasn’t emphasized.

“In most cases, people participate in these drills and don’t get more anxious and fearful. But that could certainly happen. And we want you to know that you’re not alone,” Nickerson says. She emphasizes that “it’s a giant strength ⎯ not weakness ⎯ that you’re able to identify a problem that you need help with.”

Beyond drills

“Engaging students in safety doesn’t just mean practicing for these worst-case scenarios,” says Gay, the Sandy Hook parent. Her group encourages students to start safety clubs. Service projects by club members can help schools spot possible dangers sooner. They also give students a voice in school safety planning. Other groups aim to decrease bullying. Some school shooters had been victims of bullying.

When it comes to school violence, “there are often warning signs,” says a February 2020 report from the Everytown Gun Safety Support Fund and teacher and student groups. Spotting those signs can help educators take action to prevent violence before it happens.

Stricter laws on gun storage also can keep firearms out of many shooters’ hands, the groups say. And often a shooter may target classmates at a school he or she attended. So, the report argues, “safety drills with students may be ineffective” because they would share preparedness steps with the people most likely to carry out a shooting.

Other prevention efforts aim to beef up school security. Many schools have limited entry to no more than one or two doors. Many have added security cameras. Some schools also have added metal detectors and even armed staff members or regular police patrols. It’s unclear whether such measures make students much safer or just introduce extra risk. Their impacts on students also vary. A lot depends on the particular community.

A student’s’ race can make a difference too, says Bryan Warnick, an education expert at Ohio State University in Columbus.

Aalayah happens to be Black. She says her last year of high school in Parkland “was pretty uncomfortable for kids that looked like me.” The school didn’t have metal detectors, but it added some armed guards with rifle cases. “That’s really uncomfortable and triggering for people that were directly impacted by the shooting,” she says. “And also uncomfortable for students of color because we are not greeted nicely by police officers.”

In any case, she argues, extra school-security steps and shooter drills are “just a Band-Aid on the real issue.” Mass shootings at schools and other places are terrible tragedies. Yet they account for fewer than two in every 100 U.S. gun deaths, data from the Pew Research Center show. Those shootings get lots of media attention. Yet there are many more gun deaths from suicide, domestic violence and other murders.

“We don’t need active shooter drills,” Aalayah concludes. “We need actual legislation that will prevent gun violence from entering our schools and other places.”