Don’t flush your contact lenses

The plastics in them can pollute water and be mistaken for food by aquatic animals

One in five people who wear contact lenses flush their used eyewear down the sink or toilet. That plastic pollutes the environment and can harm wildlife.

STUDIOGRANDOUEST/iStockphoto

If you wear contact lenses, you might not know the best way to discard old ones. Hint: Washing them down the sink or flushing them down the toilet are not the way to go. Yet one in five people who wear contacts do just that. The bad news: The plastic in their lenses can linger, polluting both water and land.

Researchers quantified the problem, this past August, at the American Chemical Society meeting in Boston, Mass. Rolf Halden was one of them. This engineer at Arizona State University in Tempe also described his team’s findings for reporters at a press conference from the meeting.

Halden studies ways to reduce pollution’s effect on the environment. Many people need contact lenses every day for work and play. Until now, he notes, scientists hadn’t studied what happened to these soft plastic disks after use.

But having worn contact lenses for many years, he could relate to the issue. One day, he thought about what happens to all of those disposable lenses after people are done with them. He and his graduate students, Charles Rolsky and Varun Kelkar, designed some tests to find out.

They started by creating an online survey. More than 400 contact lens wearers took part. The questions asked how many disposed of their lenses improperly. About 20 percent — one in five — sent their used contacts down a sink drain or toilet.

Assuming all U.S. contact-lens wearers do that at the same rate, the researchers then calculated how much plastic would be flushed away each year. Their estimate: 6 to 10 metric tons! That’s about the weight of two to three adult African forest elephants.

Contact lenses are a tiny part of the world’s plastic pollution. A total of 8 million metric tons of plastic end up in the world’s oceans each year. But the unique chemistry of the plastic used in contact lenses could make them a big concern, says Terry Collins. He’s director of the Institute of Green Science at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pa. He wasn’t involved in the study.

A new form of pollution

Wastewater treatment plants clean the water that washes down drains or that exits toilets. They separate out raw sewage (things like poop as well as other items, such as twigs and garbage) and use microbes to clean the rest of the water. Then they release the water into lakes and rivers. In the laboratory, Halden’s team probed what would happen to contact lenses at a treatment plant.

Contact lenses are made from soft plastics. They are a type of long chain-like molecules known as polymers (PAHL-ih-murs). Each link in the chain holds onto to its neighbors by chemical bonds.

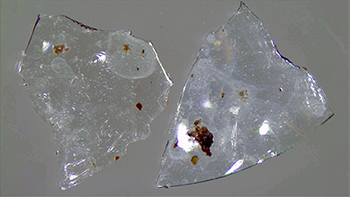

To find out how the wastewater treatment process affects those bonds, the researchers exposed contact lenses to the microbes found in water-treatment plants. These microbes broke some of the chemical bonds. This caused the plastics to begin to fall apart. But they didn’t fully degrade. Instead, they created a lot of tiny bits of debris. Scientists refer to those bits as microplastics. And those would wash out of the water-treatment plant, along with the “cleaned” water.

“Contact lenses are a very new form of plastic pollution,” said Halden. He hopes that others will study these plastics, too.

Environmental scientists have been finding microplastics everywhere, from the ocean floor to mountaintops. And that concerns them, says Collins, because the chemical bonds that remain in these smaller plastics are “almost indestructible.” That could allow the pollution to persist for a long time.

Wildlife can view this pollution as food

Collins, Halden and others worry that these small plastic bits will cause trouble in the food chain. In water, the plastics from contact lenses sink. Animals could view these tiny bits as food. But because the plastic won’t provide them nutrients, this could threaten the health — certainly the growth — of animals who dined on it.

And that’s already happening. Many studies have shown that corals, larval fish and shellfish are mistaking microplastics for food. Any animal that eats these polluted prey will get those plastics into its body, too. Over time, they risk accumulating ever higher levels of plastic in their bodies. The pollution can reach people, too. It has already shown up in bottled water, sea salt and fish sold for human consumption.

Scientists don’t yet know whether a build-up of microplastics will harm most aquatic animals and people. But its presence is not a good sign. Among other problems with these plastic bits: They tend to accumulate many of toxic water pollutants. These can include pesticides, fossil-fuel wastes and polychlorinated biphenyls. Plastic bits that carry these pollutants now risk bringing them into the diet of animals — including people.

So what should people do with their used contact lenses? Throw them in the garbage rather than flushing them, Halden says. Urging contact lens makers to recycle used lenses might help, too. Chemists might also try to design new plastics, he says. Their goal: plastics tough enough to do their job, but that degrade when no longer needed.

People need to be more aware of plastics, Collins says. “We throw plastic away without much thought. Any solution [to this pollution],” he says, “must involve changing the way we think about — and use — plastic.”