Don’t let the bedbugs bite

Three teens discovered a cheap and easy way to kill bedbugs without using pesticides

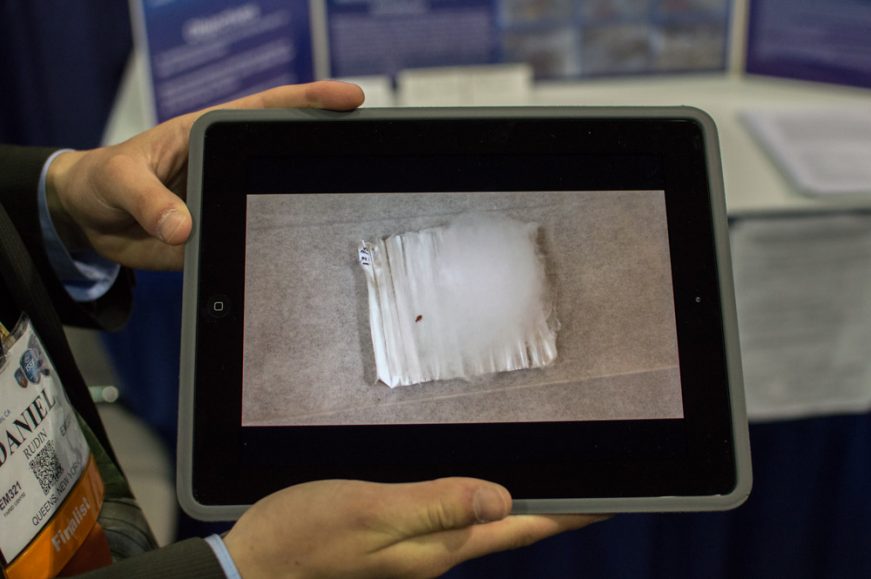

This fluffy wad of material (shown in the image on a tablet) is made from recycled plastic. Its microfibers are so small that a bedbug’s legs can get tangled in them. The insects (one shown trapped on the material, near center) become so firmly stuck that they die before they can escape.

Patrick Thornton/SSP

By Sid Perkins

LOS ANGELES — In many areas of the United States, bedbug populations are booming. But three New York teens have come up with a new way to fight the plague. They invented a bedbug-trapping fiber. The inexpensive material is made from recycled plastic. Best of all, it works without harmful chemicals.

The achievement earned the students from Half Hollow Hills High School West in Dix Hills, N.Y., spots as finalists, last week, here at the International Science and Engineering Fair, or ISEF. The competition was created by the Society for Science & the Public and is sponsored by Intel. Each year, Intel ISEF showcases some of the best high school science projects from around the globe. (SSP also publishes Science News for Students.)

In the long fight between humans and the common bedbug, people had the advantage for many years. Chemical pesticides successfully poisoned the biting animals. Then, many of these bloodsucking, come-out-at-night parasites evolved resistance to the pesticides (so the chemicals no longer poisoned them). Today, bedbugs are a growing health menace. Beyond making people really squeamish, their bites can cause skin rashes and welts that resemble mosquito bites.

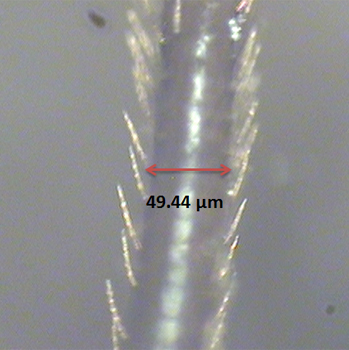

To tackle the bedbug problem, Daniel Rudin, 17, Michal Leibowitz, 17, and Jacob Plaut, 18, began by looking at the insect’s anatomy. Under a microscope, they saw that the bugs’ legs were covered with tiny spines. These stiff, hair-like structures pointed slightly upward toward the insect’s body. They looked a bit like the barbs on a fishhook. And that gave the teens an idea: Maybe those barbs would catch in a mat of fibers if those fibers were the right size.

Natural fibers, such as cotton, were too large to fit in between the bugs’ leg spines. That means the bugs could walk right over cotton without getting caught, Daniel explains. So the team turned to synthetic materials. They looked at plastics that could be squeezed through tiny nozzles to make microfibers.

For their next round of experiments, the teens focused on three different materials. One called polylactic acid, or PLA, is recycled from used plastics. The second material, called ecoflex, is a recycled plastic that had been designed to break down over time (it can also be made from natural materials). The third material is a plastic made from recycled Styrofoam cups.

The teens dissolved each plastic into a liquid and gave it an electric charge. Then the teens squeezed the liquid out of a nozzle near a metal plate that had the opposite electrical charge. That attracted the liquid stream to the metal plate, Jacob explains. As this stream passed through the air, part of the liquid evaporated. That left behind a thin plastic fiber that piled onto the plate like one long, very thin string of spaghetti.

The tiny spines on a bedbug’s legs are, on average, spaced about 83 micrometers apart. Fibers spun from PLA and ecoflex proved too big to slip between those leg spines. But the recycled-Styrofoam fibers typically were less than 2 micrometers in diameter. They easily fit, Michal told Science News for Students.

Fibers made from recycled Styrofoam created a big pile that looked like a fluffy cotton ball. Spaces between the fibers allowed a bedbug’s legs to penetrate. But once the insect tried to withdraw its legs and take another step, the leg spines got caught. The plastic fiber “acts sort of like Velcro,” says Daniel.

The new material isn’t sticky like flypaper or other insect-trapping substances, so people might like using it, Michal says. Plus, it’s easy to use: Simply tape a ring of this material around the legs of a bed. Ascending bugs can’t climb past it to reach a mattress or sheets.

The new material has another benefit: Using it could be much cheaper than using pesticides, Daniel says. Right now, treating a home for bedbugs can cost between $1,000 and $3,500. But the new material can be made for pennies, he notes.

Power words

bedbug A parasitic insect that feeds exclusively on blood. The common bedbug, Cimex lectularius, sucks human blood and is mainly active at night. The insect’s bite can cause skin rashes and welts that look like a mosquito bite.

parasite An organism that gets benefits from another species, called a host, but doesn’t provide it any benefits. Classic examples of parasites include ticks, fleas and tapeworms.

pesticide A chemical or mix of compounds used to kill insects, rodents or other organisms harmful to cultivated plants, pet or livestock, or unwanted organisms that infest homes, offices, farm buildings and other protected structures.

pesticide resistance The ability to survive being sprayed or treated with pesticides.

PLA (abbreviation for polylactic acid) A plastic made by chemically linking long chains of lactic-acid molecules. Lactic acid is a substance present naturally in cow’s milk.

recycle To find new uses for something — or parts of something — that might otherwise be discarded or treated as waste.