Electric currents in the air may cue ‘ballooning’ spiders on when to take off

In the lab, spiders prepared to ‘fly’ when researchers turned on an electric field

Spiders don’t have wings, but that doesn’t mean they’re stuck on land. Carried on a parachute of silk strands, spiders have been known to drift kilometers above Earth’s surface. These so-called ballooning spiders may even soar across oceans to reach new habitats. Electrical charges in the air might provide a cue on when to fly, new research suggests.

This invisible signal might help explain why spiders’ takeoff timing is so unpredictable. Some days, large numbers of spiders balloon together. On other days, they stay firmly grounded despite similar weather conditions.

When conditions are right, some spider species climb to a high point. There, they release silken strands as they await the breeze needed to help them soar away.

To take off, spiders need gentle air currents. Past studies had shown that wind speeds under 11 kilometers per hour (7 miles per hour) were best. But such a light breeze shouldn’t be strong enough to get some of the larger ballooning-spider species off the ground, points out Erica Morley. She’s a sensory biologist at the University of Bristol in England.

As a result, she notes, scientists have long wondered if some other force might be involved.

For example, electrical charges in Earth’s atmosphere form a field that attracts or repels other electrically charged objects or particles. This electric field varies in strength. It grows around objects such as leaves and branches on trees. It also fluctuates with the weather. Under the right conditions, could these electrical charges push against the silk threads of a spider’s parachute — fanning them out to keep a spider aloft?

Morley and Daniel Robert, a sensory biologist at the University of Bristol, decided to find out if spiders can sense these electric charges. First they blocked natural electric fields in a lab. They then artificially created an electrical field. It mimicked what spiders in the wild could experience. Linyphiidae is the second largest family of spiders. The scientists placed teeny-tiny spiders from that family into that electric field.

Even with no breeze, when spiders sensed this field, they perched on the tips of their legs. Spiders use this ballerina-like pose before they balloon. Scientists call it the “tiptoe stance.” When the researchers turned off the artificial electric field, the spiders got off their tiptoes.

The researchers shared their findings July 5 in Current Biology.

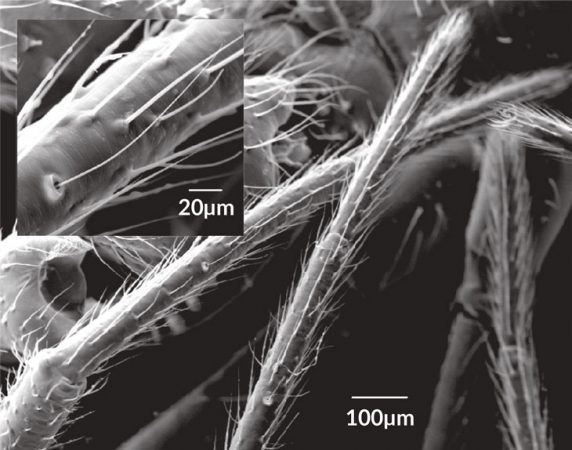

The effect is hairy

Tiny hairs on the spiders’ bodies react to moving air and to electric fields, the researchers found. But they don’t react to both in the same way. As long as air was blowing on them, the hairs stood on end. With an electric field, the hairs stood up most dramatically when the field switched on. Over the next 30 seconds or so, those hairs gradually fell back to their resting position.

These new findings link the pre-flight tiptoe pose to the presence of an electric field. But spiders might need something more to actually take off, adds Moonsung Cho. He studies aerodynamics in Germany at the Technical University of Berlin. Explains Cho, who wasn’t involved in the study, some spiders in the study did float away. The researchers did not, however, measure that liftoff behavior.

Cho has studied ballooning in a different family of spider. The ground crab spiders seem to sense wind speed with their legs before going aloft. They wiggle one spindly leg around to sense moving air and decide whether wind conditions are right for flight. Cho’s team reported this finding June 14 in PLOS Biology.

So responding to electric fields probably isn’t the full story when a spider decides it’s time for takeoff.