Electronic paper turns a page

Changeable ink and battery-powered paper may make textbooks lighter and bring video newspapers into daily use.

By Emily Sohn

If you’ve ever tried to do lots of online research for a school report, stayed up late playing computer games, or gone on an instant-messaging marathon with some friends, you probably know what I mean.

Whenever deadlines force me to stare intently at a computer screen for hours, I get terrible headaches. My eyes start to smart. Sometimes, I have to go for a walk or lie down until waves of dizziness pass. As much as I hate to waste paper, I usually print out information I really need, and I get the newspaper delivered every morning so I don’t have to read it online.

Someday soon, though, we might be able to have our computers and read them, too. It would be like having computers built into the pages of a book or a magazine.

At a company in Massachusetts called E Ink, a team of chemists, engineers, and computer scientists are working to make electronic paper a reality. The battery-powered paper would be easy to read in bright sunlight or in dark subway trains. It would be flexible and foldable. It would feel a lot like paper.

But electronic paper would also be a display. Coated with a special type of electronic ink, each sheet would be infinitely changeable. Just one page could hold and display the contents of many books. It might even receive e-mails or include full-color video clips, as in Harry Potter’s newspaper, The Daily Prophet.

|

|

Example of an electronic-paper display.

|

| © Philips |

Electronic paper might one day serve as the vehicle for a low-cost stream of information to schools all over the world. And, while students today often strain their backs with the hefty books they have to lug around in their backpacks, students of the future might get by with only one textbook. It would be electronic, and its pages would change with the touch of a button.

Ultimately, we are trying to create the “last book,” says Darren Bischoff of E Ink. It would be “one book that could be all books.”

Beach reading

Joseph Jacobson, E Ink cofounder, was sitting on the beach when he first dreamed of creating electronic ink. He had just finished reading a novel and wished that he didn’t have to get up to go buy another one. Wouldn’t it be great, he thought, if he could simply turn the book he had just read into a new one?

Scientists had been working on electronic paper since the 1970s, but technical difficulties kept getting in the way. Jacobson is a physicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Laboratory. So, he embarked on a new series of research projects to come up with a fresh approach. With the help of two undergraduate students at MIT, Jacobsen found a promising technology, and the team launched E Ink in 1997.

Electronic-paper technology relies on tiny spheres called microcapsules. Several industries already use microcapsules. Scratch-and-sniff stickers, for instance, enclose smelly chemicals in tiny bubbles that burst open when you scratch them. Drug companies also use microcapsules to make time-release pills.

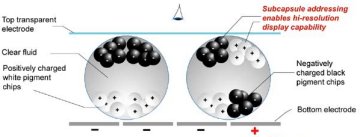

E Ink’s microcapsules are filled with a clear liquid that holds very small particles. Some particles are black. Some are white. All of the particles have an electrical charge. To make a sheet of electronic paper, engineers spread millions of the particle-filled microcapsules onto a piece of plastic.

|

|

A microcapsule of electronic ink contains black and white particles. When the bottom electrode has a negative charge, it attracts the positively charged white particles. Black particles are left on top, so the top of the microcapsule appears black (left).

|

| © E Ink |

Because opposite electrical charges attract, applying a positive electric field to a microcapsule causes negatively charged black particles to rise and become visible—just like answers in a Magic 8-Ball. The positively charged white particles sink. So you would see a black dot at this spot.

By controlling electric field patterns, engineers can decide which particles rise to the top. The resulting patterns of black and white dots, viewed from a distance, create the words and pictures you see on the sheet. To move the ink around, computer programs simply change the electric fields. The pattern of black and white dots changes in turn.

Electronic paper is much easier to read than typical computer screens, Bischoff says. Many traditional displays count on lights inside the machine to light up the screen from behind, for example. That makes such screens easy to see when you’re indoors, but they’re hard on the eyes and difficult to read in bright sunlight.

Electronic paper, on the other hand, reflects the light around it. “If you can read the newspaper, you can read our display,” Bischoff says. “It’s a much clearer, crisper, easier way to read text on a display.”

E Ink’s electronic paper also sucks up a lot less power than ordinary computer displays do because the particles stay where they are until an electric field makes them move. Images on a computer screen have to be lit up and constantly refreshed.

Changing signs

So far, applications for E Ink’s technology have been limited. In one effort, the company has made large, changeable store signs that get people’s attention or give information to shoppers.

|

|

One early application of electronic-ink technology was for flexible, changeable store signs.

|

| © E Ink |

“One thing I’m learning is that making something look good once [in the lab] is so much easier than making a product,” says Brian Hone, a software engineer at E Ink.

In fact, it takes a long time and a lot of hard work to go from something that works in the lab to a reliable, safe, easy-to-use product that people can buy. Most technologies, including CD-ROMs and DVDs, have taken at least 10 or 20 years to go from concept to market, Bischoff says.

Still, E Ink’s first commercial electronic reading device is set to come out in Japan next year, Bischoff says. Japan is a natural place to start, he says, because people there spend hours every day commuting to and from work on crowded trains.

If you’ve seen Japanese or Chinese writing, with its arrays of complicated characters, you might get a sense of why a light, compact electronic-paper display that can hold a great deal of information would be attractive.

E Ink isn’t the only company trying to make electronic paper and ink. The Xerox Palo Alto Research Center is working on a reusable electronic paper that it calls “Gyricon.” A Gyricon sheet has millions of tiny beads in oil-filled cavities. Each bead is half black and half white, and it can rotate to show one color or the other.

Another company is using particles in microcapsules filled with air instead of liquid. And scientists in the Netherlands have used a thin film of oil over colored dots to make moving images with lots of brilliant colors.

With all this activity, there’s bound to be some form of electronic or even video paper in your future. Harry Potter will always be a fictional character, but some pieces of his magical world may yet become part of your daily life.