Enthusiasm and reward for science

Meet the high schoolers who won the 2011 Intel Science Talent Search

For Evan Michael O’Dorney, the road to the White House began when he was a toddler, pulling counting books from library shelves and asking his mother to read them. Michelle Abi Hackman’s journey began when a teacher recommended a book of science essays, and Hackman realized that science extends far beyond the classroom. For Matthew Miller, it started with a slingshot and a bad idea. He and his brother, as children, used their water balloon launcher to shoot rocks over the house — then tried to catch them on the other side.

“We broke the backboard of the basketball goal in the process,” Miller remembers.

On March 15, those three individuals ― now all about to graduate from high school — became the top three winners of the 2011 Intel Science Talent Search, a national science competition and program of the Society for Science & the Public (the organization that publishes Science News and Science News for Kids). For his work on what had been an unsolved math problem, O’Dorney took home the first place award of $100,000. Second place and $75,000 went to Hackman, who studied what happens when teenagers are separated from their cell phones. Miller took home the bronze and $50,000 for studying a way to make wind power generators more efficient.

The Intel STS is among the most prestigious science competitions. Every year, high school students from around the country enter the competition (1,744 this year). Eventually, 40 students are chosen as finalists aiming for the top 10 awards.

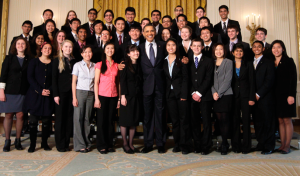

These 40 travel to Washington, D.C., for a week of science in the nation’s capital. During their visit, they meet each other and present their projects to the public. This year’s finalists also met a local, self-professed fan of science, President Barack Obama.

“He shook each of our hands, and I nearly melted,” Hackman says. “He has a genuine passion about science.”

Each of the three top winners ended up in Washington through a combination of hard work, help from others and ― most important — irresistible curiosity.

O’Dorney, who is from Danville, Calif., says he’s been interested in mathematics for as long as he can remember. Those early days of discovering numbers in the library books led to more books and headier math, including “a lot of mathematical ideas that aren’t taught in school,” he says.

Not that O’Dorney has spent much time in traditional classrooms. He has been homeschooled all his life, and his mother encouraged his strong curiosity for numbers and math. When he was high-school aged, O’Dorney began taking math classes at the University of California, Berkeley, where one of his professors made him a deal: If O’Dorney could solve a certain problem, he wouldn’t have to take the final exam. O’Dorney, up for the challenge, got to work. After a few days, he emailed a solution to his professor.

O’Dorney wasn’t only correct; he had made history. The professor told O’Dorney that he had solved an open problem, which is a mathematical question that has yet to be answered. For the Intel STS competition, O’Dorney solved another open problem: He found a connection between two different methods used for determining the square root of a number. (Two is the square root of four because two times itself is four: 2×2=4. Three is the square root of nine. The square root of a number is another number which, when multiplied by itself, gives you the original number.)

The young mathematician, not surprisingly, plans to study math all his life, as a mathematics professor. But he hopes to keep up with his other main passion: music. A pianist, O’Dorney accompanies the children’s choir at his church, and he improvises music on the piano. In the fall, O’Dorney will move to Cambridge, Mass., to begin his studies at Harvard University. He plans to study mathematics and music.

Like O’Dorney, second-place winner Michelle Hackman’s passion for science is rivaled by her passion for music, though her instrument of choice is her voice. As a child, Hackman knew she wanted to do something that would benefit many people. And as a child, she dreamed of becoming a famous singer. But over time, that dream grew and changed. By high school, she had become fascinated with human behavior.

In particular, she wanted to study how technology influences the ways people act. Hackman, who is blind, relies on technology in her own life, but her research was driven by a curiosity about how technology influences the way people act around each other.

Her award-winning project began one night when she was having dinner with her friends. Everyone was texting; no one was talking. Hackman marveled at the way the phones had changed basic communication. Suddenly, she had to know: Why are we so attached to our cell phones? And, more specifically, do cell phones make us more, or less, anxious?

“No one had answered that question,” she says. “I went back to the basics.”

Hackman enlisted 10 assistants and set up an experiment using 150 of her fellow students. Students in one group were separated from their cell phones; the rest were allowed to keep them. Hackman wanted to know whether students without cells suffered more stress. At the end of her experiment, Hackman measured no difference in anxiety between the kids who kept their phones and those who didn’t. She does, however, suspect that people without cell phones may be more attentive.

Hackman says she was surprised to discover that science can be done outside a laboratory. The key to her success, she says, was to ask a good question: “If you choose a question that really truly fascinates you, your genuine enthusiasm will shine through in the work.”

Hackman’s enthusiasm shines in other ways, as well. Inspired by an editorial in the New York Times, she and a friend worked to raise money to help start a school in Cambodia for girls who otherwise wouldn’t have a chance to attend school. Next year, when she goes to Yale University, Hackman says she hopes to join the glee club, study psychology and write for the school paper.

Eventually, she says, she wants to combine behavioral psychology with her interest in writing, and become a science journalist.

Like Hackman, third-place winner Matthew Miller, from Elon, N.C., says you don’t need a laboratory to do science. He has come a long way since he and his brother shattered that basketball backboard ― though he still follows the same approach: Ask a question, set up an experiment.

Science runs rampant in Miller’s family: His mother is an engineer, his father is a physician and his brother studies engineering at college. During his sophomore year of high school, Miller embarked on the project that would eventually lead him to Washington. He knew about previous experiments that have shown how small bumps on humpback whales’ flippers help the giant animals glide through the water. He decided to go a step further and find out whether little bumps might also improve the ability of a wind turbine to generate electricity from wind. (A wind turbine is a giant windmill.)

So Miller built a mini version of a turbine with bumps on the blades — in his family’s garage. He placed the turbine in a wind tunnel (which he also built) and found that the bumps did boost efficiency. He tested his experiment using a nearby university’s wind tunnel and found an even bigger boost from the bumps. Miller’s award-winning engineering project could help scientists find new ways to get energy from renewable sources such as wind.

Miller says his project wasn’t always easy, but he thinks the reason he succeeded is because he didn’t give up. “Nothing ever goes as planned,” he says. “There are always bumps in the road, and sometimes it would be pretty easy to can the whole idea.” The end product is worth it, he says, and young scientists should tell themselves not to give up, even when they stumble.

Like Hackman and O’Dorney, Miller uses his talents in other ways too. He plays for his school’s tennis team, produces videos for local organizations and has visited El Salvador on a medical mission trip with the faith-based group Global Health Outreach. In the fall, Miller plans to attend either North Carolina State University or Clemson University.

The research projects of the top winners couldn’t be more different, but the three young scientists had much in common, including curiosity, perseverance and help. Elizabeth Marincola, president of the Society for Science & the Public, says this year’s Intel STS finalists ― all 40 of them — “distinguished themselves in a wide variety of sciences.”

She says the science competition gives the general public a chance to get a glimpse of the talent among younger generations. Seeing this talent is especially important, she adds, since we often hear that students in the United States are falling behind in mathematics and science.

“It’s heartening for American people to see American students that are making contributions that are important,” she says. Plus, the competition gives youngsters an incentive to think and experiment at a high level.

Past participants in the program have gone on to win Nobel prizes, Fields Medals (for mathematics), MacArthur Foundation “genius grants,” National Medals of Science and other prestigious awards, including an Academy Award. Actress Natalie Portman, who won an Oscar this year for her role in the film “Black Swan,” was a semifinalist in the Intel STS competition in 1999.

You never know where these bright kids will shine in the future, so stay tuned. And ask interesting questions.