Senses help the brain interpret our world — and our own bodies

Most people can name sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch, but there are others, too

The brain plays a central role in the processing of human senses.

Elena Medvedeva/iStock/Getty Images Plus

The senses help animals interpret their world. Some animals rely on unique senses. For example, bats and whales use echolocation (Ek-oh-loh-KAY-shun) — a sort of sonar system — to improve their understanding of the placement of things in their environment. Some fish can detect electrical fields around them. We humans rely on other ways to sense what’s in and around us.

Our sensory systems use signals coming to us from both outside and inside our bodies. Senses can also be shaped by experiences and feelings. It’s the brain’s role to make sense — literally — of all those incoming data. Indeed, most sensory information is meaningless until processed by the brain.

Some senses work from a distance, others only upon contact. For instance, we can see objects many kilometers (miles) away. But smell and taste rely on detecting chemicals in the air or in your mouth. To taste something, it needs to touch receptor cells in your mouth or other parts of the digestive tract.

Some senses work together. For instance, smell, touch and taste combine to give us flavor. Vision and hearing can work as a pair to help us read other people’s lips.

Experts vary on how many senses humans use. But below are the ones most commonly described.

Sight: This is how we understand what’s in front of our eyes. Eyes are the primary organs for sight. Light entering them activates light-sensing cells in the back of the eye. There are two types of these photoreceptors: rods and cones. Cones help us perceive color. Rods help with low-light (night) vision. Both types of receptors send electrical signals to the brain through the optic nerve. The brain transforms those signals into visual images.

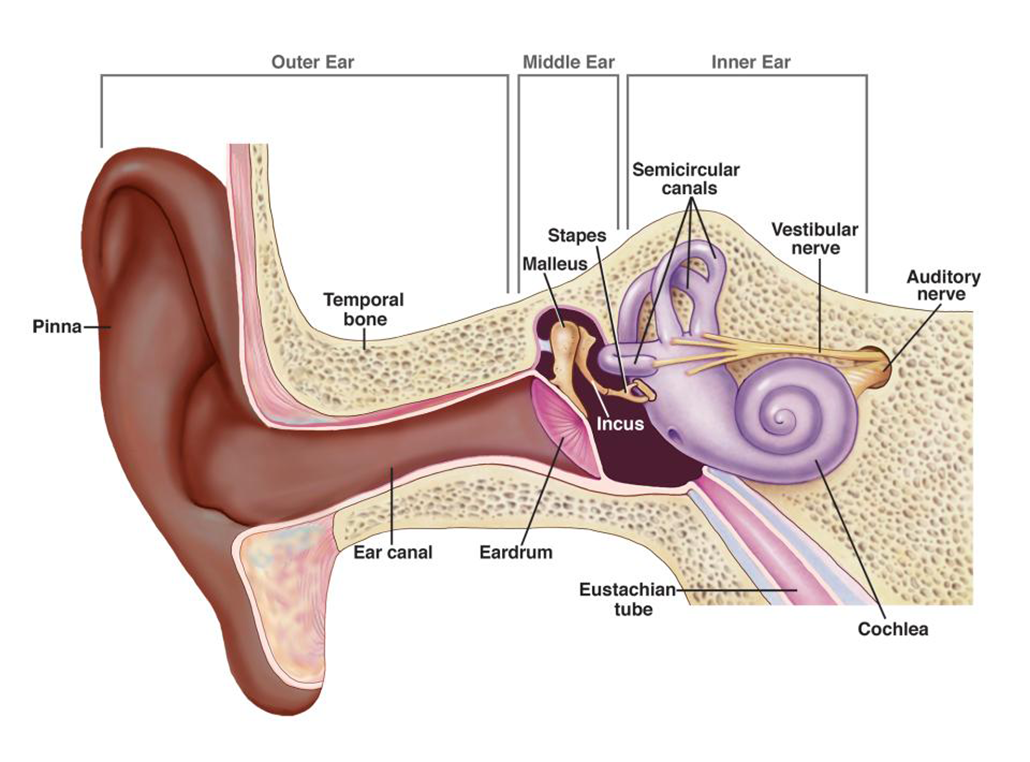

Hearing: Sounds enter our bodies through our ears. Each outer ear is like a funnel. It collects sound waves arriving from different angles and directs them to the ear canal. The waves vibrate the eardrum. Its movements shift small bones in the middle ear. These send the vibrations to the inner ear, to a snail-shaped structure called the cochlea (KOKE-lee-uh).

The cochlea holds a liquid that moves in response to vibrations. The liquid’s motion will move nearby sensory cells called hair cells. Different hair cells respond to different sound frequencies. Their motion will then trigger an electrical signal that moves down the auditory nerve to the brain. It’s the brain, again, that interprets what this system has sensed.

Smell: Also known as olfaction, smell works by detecting scent molecules in the air. After entering the nose or mouth, these molecules bind to specific receptors. Those receptors send electrical signals down the olfactory nerve to the brain.

Taste: Like smell, taste is a chemical sense. The tongue is full of taste buds. But they appear in other places as well, including the lungs. These buds have sensory cells that respond to certain chemicals in food. Nerve fibers on the taste buds relay signals to the brain to help the body interpret what you’re eating. There are five basic agreed-upon tastes: sweet, salty, sour, bitter and savory (also known as umami). However, some scientists believe there may be more taste sensors, including one for fat.

Touch: Touch is one of the first senses to develop in babies. It plays a key role in helping infants bond with caregivers. The sense of touch relies on specialized neurons found throughout the skin. When stimulated, these neurons send signals to the brain.

Sometimes, touch is divided into specific categories. These include pressure, temperature, vibration and pain. But some experts argue that each of these is its own sense. Why? Because these sensations rely on different receptors and nerve endings.

Proprioception: Your brain tracks when, where and how parts of the body bend and move through proprioception (PROH-pree-oh-SEP-shun). This sensory system has lots of moving parts. Neurons that sense body motions sit in the body’s muscles and tendons. They help inform the brain which parts are moving and in what way.

Proprioception helps you adapt to your environment. If you’ve ever been on a boat, when you get off you may find your body still feeling like you’re at sea. This is because proprioception helps you adapt to the movement of the ocean’s waves. Once back on land, your body uses proprioception to reorient itself to solid footing.

Vestibular sense: Somewhat related to proprioception, this sense is important for balance and spatial orientation. It’s what helps us stay on our feet and move smoothly. It also tracks changes in the head’s position and movements.

To do this, the vestibular system relies on organs in the ear that are filled with fluid. As the head moves, so does that fluid — allowing it to wiggle hair cells in the inner ear. The movement of those hair cells triggers signals to the brain about where the body is in space. For example, they help interpret if you are upright and unmoving, twirling or in the process of leaning over.

Other neurons in the brain can respond to help the body compensate for such movements. For instance, we may change our footing, arm placement or posture to keep from falling over.

Interoception: This is our sense of events happening inside us. Interoception collects information from internal organs, such as your heart, lungs, gut, bladder and kidneys. Motion, pain or other signals from our organs may help inform the brain about how hungry we are, whether we’re hot or if we’re scared (such as a rapid heartbeat). These signals can even warn when we may be about to vomit (have nausea) or need to pee (pressure in the bladder).