Explainer: What are fats?

These energy-packed molecules make life possible

Thanks to a cozy layer of fat, this seal stays warm even in frigid arctic waters.

Elena Eliachevitch/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Under thick sea ice, beluga whales forage for food in the sub-zero waters of the North Alaskan coast. Thick layers of fat — called blubber — insulate the whales against the deadly arctic cold. Almost half of a beluga’s bodyweight is fat. The same can be healthy for many seals, but not for people. So what is fat?

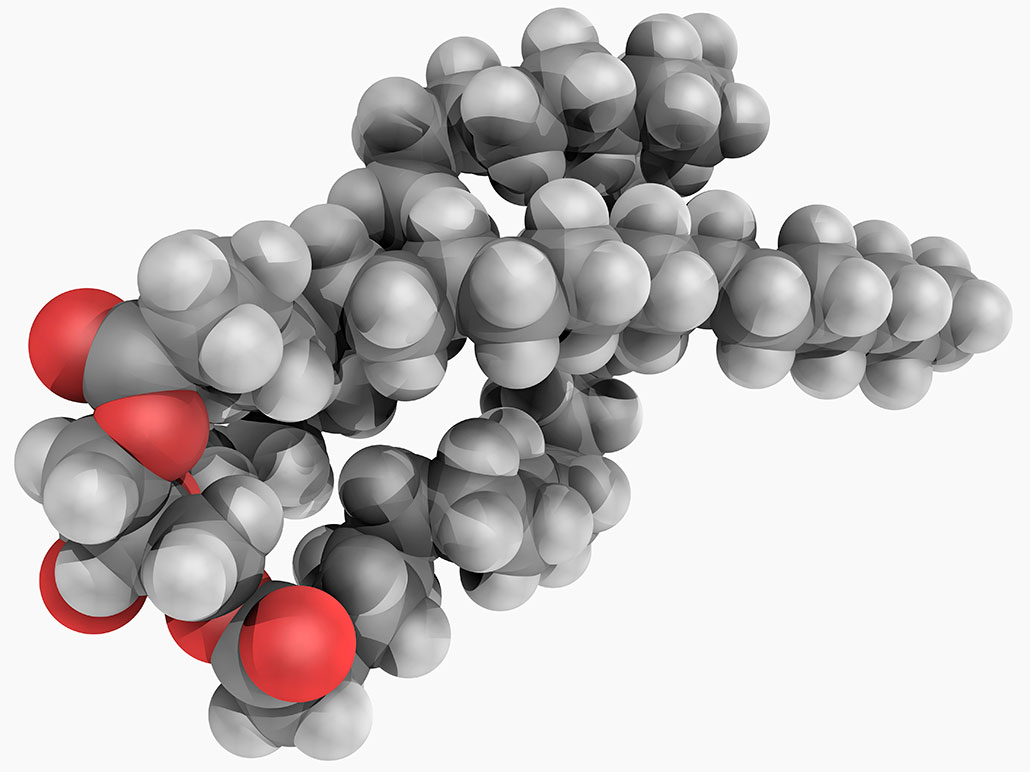

Chemists tend to call fats by another name: triglycerides (Try-GLIS-er-eids). The prefix “tri” means three. It points to the molecules’ three long chains. Each chain is a fatty acid. A small subunit called glycerol (GLIH-sur-oll) connects to one end. The other end floats free.

Our bodies build themselves from four types of carbon-based — or organic — molecules. These are known as proteins, carbohydrates, nucleic acids and lipids. Fats are the most common type of lipid. But other types exist, such as cholesterol (Koh-LES-tur-oll). We tend to associate fat with food. On a steak, fat usually lines the edges. Olive oil and butter are other types of dietary fat.

In living things, fat has two main roles. It regulates body temperature and stores energy.

Heat doesn’t easily move through fat. That allows fat to trap heat. Like the beluga whale, many other animals that live in polar environments have rounded bodies with insulating blubber. Penguins are another good example. But fat also helps keep people and other temperate mammals cool. On sweltering days, our fat slows the movement of heat into our bodies. That helps keep our body from going through big temperature swings.

Fat also serves as long-term energy-storage depots. And for a good reason. Fat packs more than twice as much energy, per mass, as do carbohydrates and proteins. One gram of fat stores nine calories. Carbohydrates store only four calories. So fats provide the biggest energy bang for their weight. Carbs can store energy, too — for the short term. But if our bodies tried to store much of it long term in those carbs, our energy lockers would weigh twice as much.

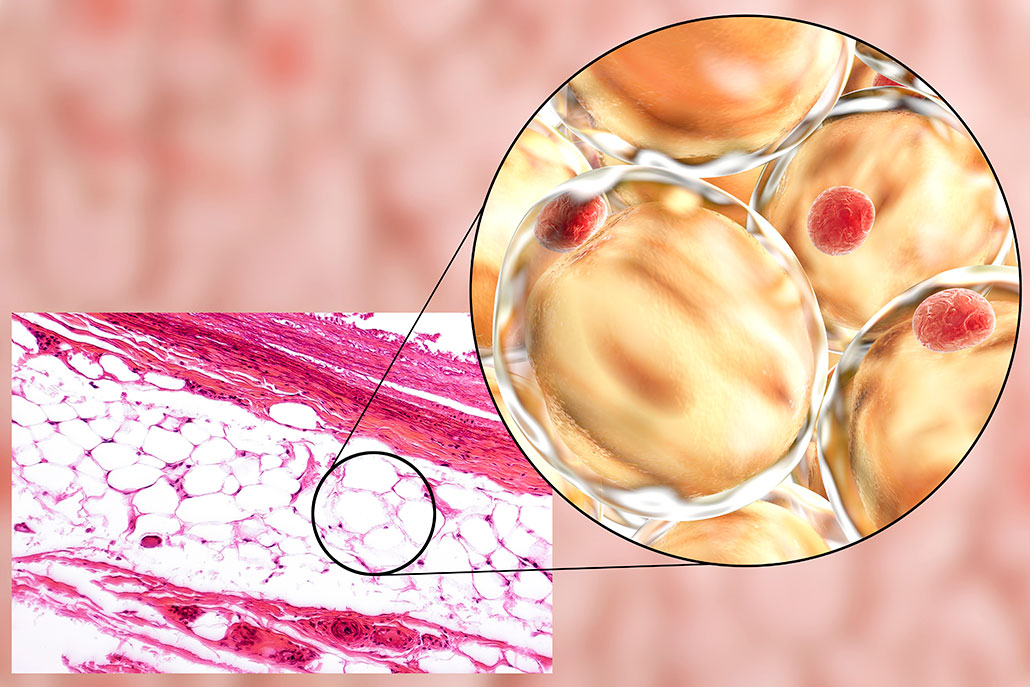

In animals, special cells store fat until we need to burn its energy. When we put on a few pounds, these adipose cells swell up with extra fat. When we slim down, those adipose cells shrink. So we mostly keep the same number of adipose cells regardless of our weight. These cells just change their size based on how much fat they hold.

One thing about all fats: They repel water. Try stirring some olive oil into a glass of water. Even if you mix them really well, the oil and water will just separate out again. Fat’s inability to dissolve in water reflects its being hydrophobic (Hy-droh-FOH-bik) or water-hating. All fats are hydrophobic. Their fatty-acid chains are the reason why.

A triglyceride’s fatty acids are made of two elements: hydrogen and carbon. That’s important because such hydrocarbon molecules are always hydrophobic. (It also explains why spilled crude oil floats on water.) In triglycerides, a few oxygen atoms connect the fatty acids to a backbone of glycerol. But other than that, fats are just a mix of carbon and hydrogen.

Saturated fats host the most hydrogen atoms

Even though butter and olive oil are both fats, their chemistry is quite different. At room temperature, butter softens but doesn’t melt. Not so with olive oil. It turns liquid at room temps. Though both are triglycerides, the fatty acids that make up their chains differ.

Butter’s fatty-acid chains look straight. Think dry spaghetti. That thin, rod-like shape makes them stackable. You can hold a big handful of those spaghetti rods neatly. They lie atop each other. Butter molecules stack, too. That stackability explains why butter must get pretty warm to melt. Fat molecules cling together, and some cling more strongly than others.

More strongly attached molecules need more heat to loosen them up — and melt. In butter, the fatty acids stack so well that separating them requires temperatures of between 30º and 32º Celsius (90º and 95º Fahrenheit).

The chemical bonds connecting carbon atoms cause their straight shape. Carbon atoms link together via three different types of covalent bonds: single, double and triple. A fatty acid made entirely of single bonds looks straight. However, replace one single bond with a double, and the molecule becomes bent.

Chemists call straight-chain fatty acids saturated. Think of the word saturated. It means something holds as much of a thing as it can. Among fats, the saturated ones contain as many hydrogen atoms as is possible. When double bonds replace single bonds, they also substitute for some hydrogen atoms. So a fatty acid with no double bonds — and all single bonds — holds the maximum number of hydrogen atoms.

Unsaturated fats are kinky

Olive oil is an unsaturated fat. It can solidify. But to do so, it must get pretty cold. Rich in double bonds, this oil’s fatty acids don’t stack well. In fact, they’re kinked. Since the molecules don’t pack together, they move more freely. That causes the oil to stay runny, even at chilly temperatures.

Generally, we find more unsaturated fats in plants than in animals. For example, olive oil comes from plants. But butter — with more saturated fatty acids — comes from animals. This is because plants often need more unsaturated fats, especially in cold climates. Animals generate more body heat than plants. Plants just get really cold. If cold made all of their fat solid, the plant couldn’t function well anymore.

In fact, plants can change the share of saturated and unsaturated fats they host to keep themselves working. Russian studies on plants growing at polar sites show this in action. When autumn arrives, the horsetail plant prepares for a bitter-cold winter by swapping out some saturated fats for unsaturated ones. These oilier fats keep the plant functional through frigid winters. Scientists reported that in the May 2021 Plants.