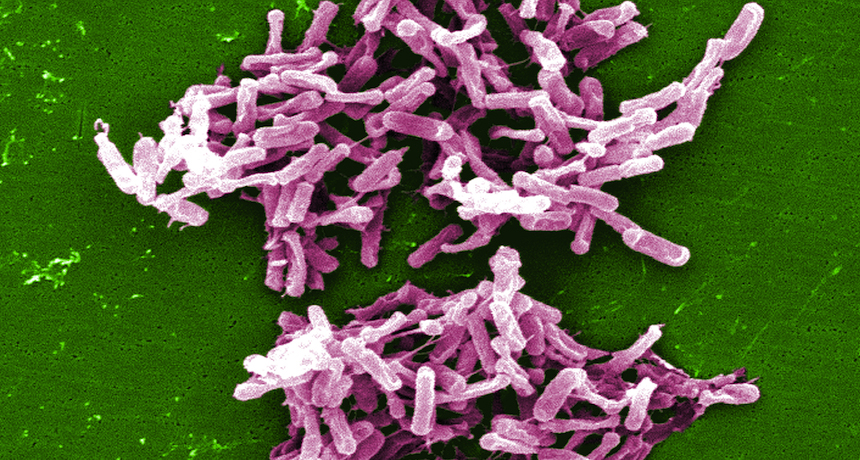

Explainer: What is C. difficile?

A severe — and often lethal — bacterial infection has risen from a rarity to a big problem

These bacteria, called Clostridium difficile, can be deadly. Scientists have developed a new and effective treatment that uses beneficial bacteria found in the feces of healthy people.

CDC/Janice Carr

By Janet Raloff

Infections due to Clostridium difficile bacteria — known as C. diff — have become a global problem. They kill an estimated 14,000 people each year in the United States alone. That’s according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, based in Atlanta, Ga. Although half of C. diff’s victims tend to be elderly, the germ can sicken anyone, even young children.

The disease causes fever, gut pain and severe, watery diarrhea. It tends to strike people who have been prescribed antibiotics for so long that the drugs have wiped out many of the good microbes in the patients’ guts. That leaves room for C. diff germs to move in and take over.

C. diff is not a new germ, but its level of threat to people is relatively new. In the mid-1990s, “we didn’t believe people died of this,” notes Sandra Dial. She’s a doctor and epidemiologist at Canada’s McGill University in Montreal. Back then, if people did die, “it was very unusual,” she told Science News. “Now,” she says, “unfortunately, it’s not unusual.”

C. diff has become such a threat because of two changes that have occurred in the past 10 to 15 years. Together, they have made the germ far more virulent, or capable of causing disease.

First, the germ underwent some mutations. These are changes to genes. Mutations are common and can occur for many reasons. Some changes may have no effect on how an organism functions. An example would be a mutation in a developing baby that transforms what would have been a blue-eyed individual into someone with brown eyes.

In other instances, a mutation can produce changes in the types or amounts of chemicals that an organism produces. In C. diff, such a mutation transformed the old-style bacteria into a new strain. While not a new species, a new strain will have new features. In the case of C. diff, this was the production of toxins, or poisons, that trigger diarrhea.

C. diff can now make three types of toxins. They’re known as A, B and binary types. Patients infected with the strain of bacteria that makes the binary toxin are most likely to develop severe diarrhea.

Initially, only a few cases of infection involved this binary-toxin version of C. diff. But over time, this strain has become responsible for more and more cases of disease.

The second change that occurred: A growing share of these especially toxic C. diff germs became resistant to antibiotics — medicines designed to kill them. That means the germs were morphing into a still worse strain, a type known as a superbug.

Many people who get a C. diff infection pick it up at a hospital or place where many sick people reside, such as a nursing home. Although antibiotics may initially appear to knock out the infection, the disease often returns. In the second or third waves of C. diff infections, antibiotics may be unable to kill off the germs. That’s one reason why doctors now choose to treat some of these hard-to-cure cases with microbes collected from healthy people. The source of those healthy microbes — feces.