Explainer: What is autism?

Autism is not a disease, but a description for a certain type of brain development

Certain behaviors may highlight traits that might suggest someone is autistic. But many autistic people, such as this girl, show no outward signs of their neurodivergent brain.

andreswd/E+/Getty Images Plus

By Payal Dhar

Autism is a neurotype, meaning “brain type.” The term describes how the nervous system — especially the brain — has developed in some people. It affects how they see, hear, feel and interact with the world.

The formal name for this lifelong condition is autism spectrum disorder, or ASD. However, some experts, including many autistic people, argue that it’s not a disorder. Instead, they explain, it’s just a different — and not-uncommon — type of brain development.

By age 8, about one in every 36 children will be identified as autistic. That number comes from 2020 data on U.S. children. A monitoring network collected these numbers for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (It’s part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.)

People are very diverse, notes Rakshita Shekhar, who lives in Germany. She was an educator who taught autistic children in India. People have different hair types and eye colors. They attain different heights and become good at different things. How the human brain develops — and functions — can vary, too. Yet over time, society has labeled only one brain type as normal, Shekhar says. “Anybody’s brain that worked differently started to be called impaired or deficient,” she says. That included the brains of autistic people.

There is no one autistic brain type, but many. Still, there are some differences between autistic and non-autistic brains. For example, certain brain structures are enlarged in autistic children and teens. (They may be in adults, too. Scientists are still studying that.) Studies also have shown that autistic brains respond differently to stimuli than do non-autistic ones.

Autism seems to be mostly genetic. Parents pass down to their children genes that have been linked to this type of brain development. Some research suggests environmental factors also may play some role. However, direct links to such non-genetic factors have not yet been proven. (One of those suspicions, that vaccines might trigger autism, has actually been disproven.)

What traits tend to show up in autism?

Because autism is not an illness, its traits are not “symptoms.” Instead, they are characteristics that help experts identify autism. Doctors tend to work from expert guidelines. Two major sets of these come from the American Psychiatric Association and the World Health Organization.

Some typical autistic traits have to do with:

- Social communication: People whose brains work in the most common way are described as neurotypical (NT). Autistic people usually find it hard to communicate with NT people. Why? They can find it hard to recognize their social cues, such as if someone is being friendly. They also tend to take things literally. For instance, they may not understand some jokes or the intent of a harmless prank. They can express their feelings differently, too — such as happiness or empathy. In some cases, they may feel far more strongly about some event than will an NT person.

Some autistic people struggle to make eye contact. They may find it hard to know when it’s their turn to speak. Some may find it hard to follow verbal instructions. If they feel overwhelmed, some autistic people can find it hard to phrase what they are thinking. In fact, some may just have other ways of communicating. For example, they may speak with a different rhythm. Or take longer to form sentences. Some autistic people are non-speaking. They may use sign language or other types of communication.

- Sensory processing: Autistic brains tend to respond to stimuli differently than do NT brains. The autistic brain might be thought of as “noisy.” That is, it may show heightened responses to sights, sounds, smells and touch.

“Some might be hypersensitive,” Shekhar says. For instance, autistic people may not like being touched. Some, she says, may even “smell colors.”

Other autistic people might be relatively insensitive. They may not pick up certain sounds or colors. Some, such as Shekhar’s son, may even need a lot of pressure on their bodies to feel calm.

Some people show patterns of repetitive behavior called stimming. These help stimulate their senses, providing comfort or a way to cope with anxiety. Examples can include rocking back and forth or flapping one’s hands.

- Attention patterns: People may describe autistic people as having tunnel vision. A term for this is monotropism (Mah-no-TROAP-izm). Monotropic brains tend to focus on just one thing at a time. “The autistic brain, when it focuses, it goes deep into the zone,” Shekhar explains. That brain “pulls in resources from all sides and puts them all into that one thing.”

It is common for autistic people to have special interests — deep and intense passions for certain subjects. They can spend a lot of time and focus on these topics. In fact, special interests play a big role helping autistic people learn and find well-being.

- Project planning: The brain manages how we get tasks done. Known as executive function, this helps us cope with novel events or things that change. Executive function helps us manage our time, plan tasks, make decisions and solve problems. Notes Shekhar, “There are huge differences in the executive function [of autistic people].” Scientists don’t yet know why, she adds. But as a result, some autistic people need a rigid routine to perform daily activities. Others need support in other ways.

These traits can vary greatly within the autistic community. So someone may show some traits and not others.

What is the autism spectrum?

Society often refers to autistic people as “being on the spectrum.” Many people think this is some scale that goes from “less autistic” to “more autistic.” In fact, all autistic people are equally autistic. What differs is how their traits vary. Some people may not even be visibly autistic. But this doesn’t make them “less” autistic.

Autistic people may have intellectual or physical disabilities unrelated to their brain type. These can be misunderstood as the person being “more” autistic. They’re not. They just have additional issues to cope with.

Imagine the autism spectrum as a color wheel. Each color represents a different trait. Each autistic person has a different intensity of that color (or trait). For example, one may have good social skills but struggle with executive function. Another may be non-speaking, but easily manage daily routines.

Depending on their profile, each autistic person may need a different type of support. Some may need help communicating, others help with getting organized. Yet others may need assistance with processing sensory data.

All of this points to how diverse the autism spectrum is. It’s also why experts no longer like describing autistic people as “high-” or “low-functioning.” Such terms don’t make sense, says Suhansini Sundaresan. She is a psychologist and counselor in Mumbai, India. Function relates to what’s natural to an individual, she says. So each autistic person functions according to their natural ability.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

What are some misconceptions?

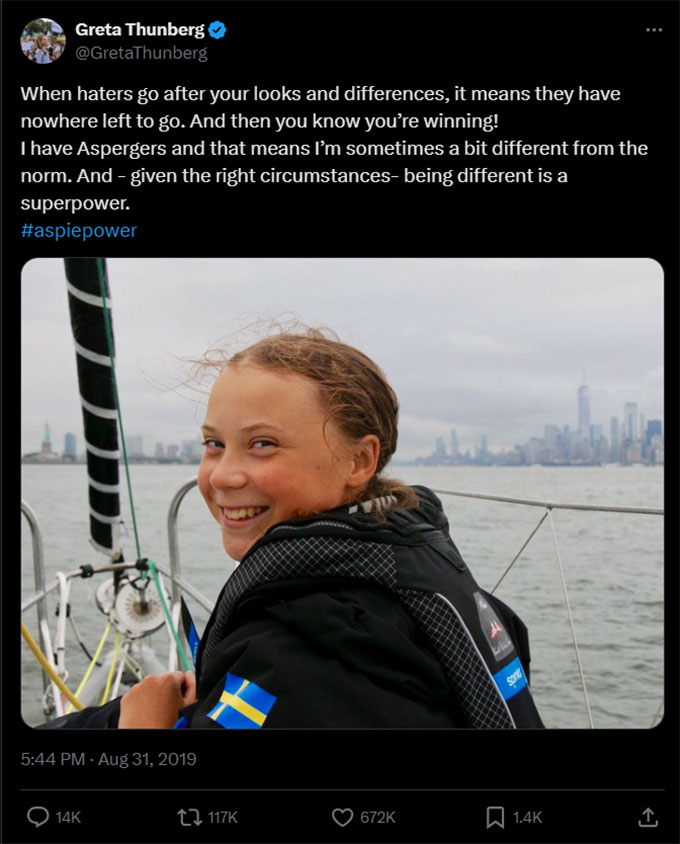

Autism shows up in every culture, every profession and every age group. Autistic people can be funny or serious, open and friendly or quiet and withdrawn. Some are even quite famous. Like climate activist Greta Thunberg, actor Dan Aykroyd and Temple Grandin, a scientist and author of many books on autism.

The biggest stereotype, says Sundaresan, is that autistic people can’t make their own decisions. But there are plenty of other stereotypes, she adds — “like they can’t communicate. They don’t have independent thought. And they can’t have a very typical day where they can have fun.” Some people believe that autistic people can’t make friends or will need help 24/7 because they can’t do things independently.

Another huge misconception: Autistic people don’t have empathy. “We do feel empathy,” Sundaresan says. “But we express it in a different way. The way we express ourselves [overall] is different.” In fact, she emphasizes, “That is the fundamental aspect of autism.”

Lastly, she and other autistic people note, many people love being autistic. In one 2019 post on social media, Greta Thunberg tweeted: “I have Aspergers.” (That’s one term for autism that’s no longer used.) And, Thunberg added, “that means I’m sometimes a bit different from the norm.” But under the right circumstances, she said, this type of being different “is a superpower.”