Explainer: What is the vagus?

This wandering nerve controls many functions, from sweating and heart rate to gagging

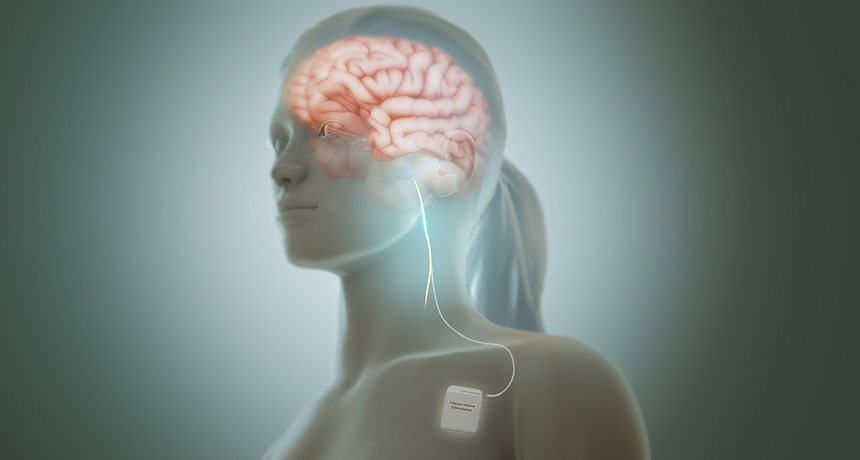

The vagus nerve runs from the base of the brain down the spinal cord, and reaches out to touch most of your organs along the way. The yellow line in this picture is the top of the vagus nerve, here attached to a small electronic stimulator. That device can be used to treat seizures or depression.

Manu5/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

It maintains your heartbeat and makes you sweat. It helps you talk and makes you vomit. It’s your vagus nerve, and it’s the information highway that connects your brain with organs throughout the body.

Vagus is Latin for “wandering.” And this nerve definitely knows how to ramble. It stretches from the brain all the way down the torso. Along the way, it touches key organs, such as the heart and stomach. This gives the vagus control over a huge range of bodily functions.

Most of the cranial (KRAY-nee-ul) nerves — 12 large nerves that leave the base of the brain — reach only a few bits of the body. They might control vision, hearing or the feel of a single finger against your cheek. But the vagus — number 10 out of those 12 nerves — plays dozens of roles. And most of them are functions you never consciously think about, from the feeling inside your ear to the muscles that help you speak.

The vagus begins in the medulla oblongata (Meh-DU-lah (Ah-blon-GAH-tah). It’s the lowest part of the brain and sits just above where the brain merges into the spinal cord. The vagus is actually two large nerves — long fibers composed of many smaller cells that send information around the body. One emerges on the right side of the medulla, another on the left. But most people refer to both the right and left at the same time when they talk about “the vagus.”

From the medulla, the vagus moves up, down and around the body. For instance, it reaches up to touch the inside of the ear. Further down, the nerve helps control the muscles of the larynx. That’s the part of the throat containing the vocal cords. From the back of the throat to the very end of the large intestine, parts of the nerve wrap gently around every one of these tubes and organs. It also touches the bladder and sticks a delicate finger into the heart.

Resting and digesting

This nerve’s role is almost as varied as its destinations. Let’s start at the top.

In the ear, it processes the sense of touch, letting someone know if there’s something inside their ear. In the throat, the vagus controls muscles of the vocal cords. This allows people to speak. It also controls the movements of the back of the throat and is responsible for the pharyngeal reflex (FAIR-en-GEE-ul REE-flex). Better known as the gag reflex, it can make someone vomit. More often, this reflex simply helps keep objects from getting caught in the throat where they could make someone choke.

Further down, the vagus nerve wraps around the digestive tract, including the esophagus (Ee-SOF-uh-gus), stomach and the large and small intestines. The vagus controls peristalsis (Pair-ih-STAHL-sis) — the wavelike contraction of muscles that move food through the gut.

Most of the time, it would be easy to ignore your vagus. It’s a large part of what’s called the parasympathetic nervous system. That’s a long term to describe that part of the nervous system that controls what happens without our thinking about it. It helps the body do things that it’s put off for when it’s relaxed, such as digesting food, reproducing or peeing.

When turned on, the vagus nerve can slow the heart’s beating and lower blood pressure. The nerve also reaches into the lungs where it helps to control how fast you breathe. The vagus even controls the smooth muscle that contracts the bladder when you pee. As noted earlier, it regulates sweating, too.

This nerve can even make people faint. Here’s how: When someone is extremely stressed, the vagus nerve can get overstimulated as it works to bring down heart rate and blood pressure. This may cause someone’s heartbeat to slow down too much. Blood pressure may now plummet. Under these conditions, too little blood reaches the head — causing someone to faint. This is called vasovagal syncope (Vay-zoh-VAY-gul SING-kuh-pee).

The vagus isn’t a one-way street. It’s really more like a two-way, six-lane superhighway. This nerve sends signals out of the brain, then receives feedback from outposts throughout body. Those cellular tips go back to the brain and allow it to keep tabs on each organ the vagus touches.

Information from the body not only can change how the brain controls the vagus, but can also affect the brain itself. These information exchanges include signals from the gut. Bacteria in the gut can produce chemical signals. These can act on the vagus nerve, shooting signals back to the brain. This may be one way that bacteria in the gut can influence mood. Stimulating the vagus directly has even been shown to treat some cases of severe depression.