Explainer: Why sea levels aren’t rising at the same rate globally

A spinning planet, melting ice sheets and warmer waters all contribute to sea level rise

Traffic keeps flowing on a flooded street in Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam. Sea levels are rising around the world, but they are rising more quickly in some places than in others.

xuanhuongho/iStockPhoto

By Katy Daigle and Carolyn Gramling

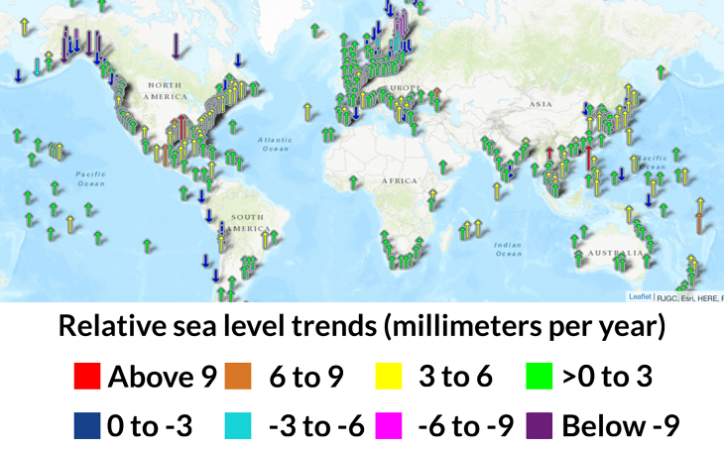

The sea is coming for the land. In the 20th century, ocean levels rose by a global average of about 14 centimeters (some 5.5 inches). Most of that came from warming water and melting ice. But the water didn’t rise the same amount everywhere. Some coastal areas saw more sea level rise than others. Here’s why:

Swelling seawater

As water heats up, its molecules spread out. That means warmer water takes up slightly more space. It’s just a tiny bit per water molecule. But over an ocean, it’s enough to bump up global sea levels.

Local weather systems, such as monsoons, can add to that ocean expansion.

Monsoons are seasonal winds in southern Asia. They blow in from the southwest in summer, usually bringing a lot of rain. Monsoon winds also make the ocean waters circulate. This brings cool water from the bottom up to the surface. That keeps the surface ocean cool. But weaker winds can limit that ocean circulation.

Weaker monsoons in the Indian Ocean, for instance, are making the ocean surface warmer, scientists now find. Surface waters in the Arabian Sea warmed more than usual and expanded. That raised sea levels near the island nation of the Maldives at a slightly faster rate than the global average. Scientists reported these findings in 2017 in Geophysical Research Letters.

Land a-rising

Heavy ice sheets — glaciers — covered much of the Northern Hemisphere about 20,000 years ago. The weight of all that ice compressed the land beneath it in areas such as the northeastern United States. Now that this ice is gone, the land has been slowly rebounding to its former height. So in those areas, because the land is rising, sea levels appear to be rising more slowly.

But regions that once lay at the edges of the ice sheets are sinking. These areas include the Chesapeake Bay on the East Coast of the United States. That’s also part of a postglacial shift. The weight of the ice had squeezed some underlying rock in the mantle — the semisolid rock layer below the Earth’s crust. That caused the surface of the land around the Chesapeake Bay to bulge. It’s a bit like the bulging of a water bed when a person sits on it. Now, with the ice gone, the bulge is going away. That’s speeding up the impacts of sea level rise for the communities that sit atop it.

Land a-falling

Earthquakes can make land levels rise and fall. In 2004, a magnitude-9.1 earthquake made land in the Gulf of Thailand sink. That has worsened the rate of sea level rise in this area. Adding to the problem are some human activities, such as pumping up groundwater or drilling for fossil fuels. Each process can cause the local land to sink.

The spin of the Earth

Earth spins at about 1,670 kilometers (1,037 miles) per hour. That’s fast enough to make the oceans move. Ocean water swirls clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere. (This is due to a process known as the Coriolis effect.) As water moves around coastlines, the Coriolis effect can make water bulge in some places, and sink in others. The flow of water from rivers can exaggerate this effect. As their waters flow into the ocean, that water gets pushed to one side by the swirling currents. That makes water levels in that area rise more than on the side behind the current. Scientists reported that finding in the July 24 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Glaciers begone

Melting glaciers also can add water to the oceans. But these huge ice slabs affect sea levels in other ways, too.

Huge glaciers can exert a gravitational tug on nearby coastal waters. That pull piles up water near the glaciers, making it higher than it otherwise would be. But when those glaciers melt, they lose mass. Their gravitational pull is now weaker than it had been. So the sea level near the melting glaciers drops.

But all that melted water has to go somewhere. And that can lead to some surprising effects, according to a 2017 report in Science Advances. Melting ice in Antarctica, for instance, could actually make sea levels rise faster near distant New York City than in nearby Sydney, Australia.

Editor’s Note: This story was updated on January 15, 2019, to correct that ocean water swirls clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the south, rather than the other way around.