Fake news: How not to fall for it

News literacy often is not taught in school even though the skill is becoming more important than ever

Finding fake news isn’t as easy as this photo makes it look.

Silvia and Frank Eschweiler-Engelskirchen/Pixabay (CC0)

A 7-year-old recently found a picture of President Donald Trump on the internet and gazed at it indignantly.

“Look how stupid he is!” she said to her dad, pointing to the image. The photo showed Trump writing his inaugural speech — with his pen turned upside down.

Of course, the image was not the original photograph. It had been Photoshopped to look like Trump was using the pen the wrong way. The girl’s dad quickly pointed out the mistake, and she got an on-the-spot education in fake news. She’s lucky that her dad, Charles Seife, has written a book about telling fact from fiction on the internet. He also teaches science journalism at New York University in New York City.

His daughter “had a pre-existing belief that Trump was stupid. And she genuinely believed the photo,” Seife recalls. “We had to have a talk about it.”

Maybe you’ve had talks like this with your own parents or teachers. Or maybe you’ve noticed on your own that some of what you see online does not seem real. Knowing how to spot fake news is just one part of news literacy. That term means being able to judge what news is trustworthy or accurate.

Many experts think learning how to consume news is just as important as learning algebra or history. To be a good citizen, they say, you need to be able to tell different types of news stories apart. You need to learn how to spot fake news. And you need to check sources and make sure they’re trying to tell the truth.

But right now, most schools do a poor job of teaching news literacy. Recent studies show that most kids can’t find fake news. And they can’t tell the difference between real news and certain types of ads.

Learning these skills “is like being able to tell the difference between the mushroom you can eat and the poisonous mushroom,” Eric Newton says. He teaches journalism at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University in Phoenix.

With both real and fake news stories flying around social media, “the idea of news literacy has become more urgent,” Newton says. That means kids need to learn to think like journalists.

Not your parents’ newspaper

Kids across the country are learning about news literacy in very different ways. Few states tell teachers exactly how to teach this skill. A kid in Chicago may go to the media center at school. There, a media specialist might teach an entire unit about how to check out sources. A teenager in California may learn about fact-checking in science class. But a student in Ohio or Pennsylvania or Montana may never hear about those topics at school.

Why is learning how to consume news so important? After all, people didn’t used to have to learn how to read news.

In fact, circumstances have changed. A lot. When your parents were your age, people read news in a much different way. The newspaper hit their doorsteps at 6:00 a.m. or 6:00 p.m., and everyone got the same news. Big headlines on the front page meant the news was important. Stories buried deep inside the newspaper generally were less important.

Now we get so much news and information that it’s like drinking from a fire hose, Michael Spikes says. Spikes is the director of the Digital Resource Center for Stony Brook University’s Center for News Literacy. He works in Chicago, Ill.

Not only are we overwhelmed with news these days, but everyone gets different news. What seems to be big news on your social media stream probably isn’t the same story that shows up on your aunt’s Twitter feed.

It’s up to each person to figure out what is important and what isn’t. It’s up to us to make sure the news outlets we read hire true journalists who want to tell the truth. And it’s up to us to know the difference between a news story and an ad — and to recognize when someone is purposely trying to mislead us with fake news.

Admittedly, this often is not easy.

One reason is that people like to read news that agrees with, or confirms, what they already think. Scientists call that tendency confirmation bias. Social media sites fill your feed with what they think you will like — not necessarily the stories that are most important.

The more that people like or share those posts, the more important they seem. Journalists are often called gatekeepers, because they control what information gets published. But there are no gatekeepers on Facebook, Tumblr or YouTube. That means it’s up to you to figure out if what you’re seeing is reliable.

To do that, think of an onion, Newton says: “You need to peel back the layers and identify what is going on. Where did that information come from?” Is the author a journalist? Where did the story first appear? Why was the story written?

Also, if you’re only seeing news that your friends share, you may be missing big events. And you may forget that not everyone thinks the way you and your circle of friends think. By only reading news on social media, Newton observes, you “may not be able to understand a large part of the country that isn’t your tribe.”

Story continues below video.

Center for News Literacy

Finding fake news

“Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own set of facts,” a famous politician, former U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, once said.

Stories that look like real news but don’t have any facts behind them are called fake news. No matter how real they look, “they’re complete fantasy and their intention is to deceive you,” Newton says. People may create fake news stories to make money or to gain political power. Or they might do it just to stir up trouble.

Chances are, you’ve already run into fake news. Here are some headlines that have tricked many people into believing they are real, even though nothing about them is true:

Obama Signs Executive Order Banning the Pledge of Allegiance in Schools Nationwide

Trump Offering Free One-Way Tickets to Africa & Mexico for Those Who Wanna Leave America

Again, both of these headlines are totally false!

The idea of fake news has become more complicated recently, because people lately have begun to use this term to mean different things. Some people are using it to describe stories they don’t agree with. But just because you don’t agree with a story doesn’t make it fake.

And sometimes, real news stories contain mistakes. While some people have labeled those stories “fake news,” that’s not right, Newton says. “Consider that a story might have 40 facts. If one is wrong, that’s a very different thing than something that’s 100 percent false,” he says. It’s not possible to get 100 percent of every story right, he says.

Even when people attempt to present credible information, they may not have the background to do it well. Some may not check their facts well, either. One internet source that should always send up a big red warning flag, Seife notes, is Wikipedia. It’s so easy to use. But there is no guarantee that the information it offers is correct. And part of that is due to the fact that anyone and everyone can contribute to the site. One does not need to be an expert to make claims on it of fact or interpretation, he explains.

In his book, Seife cites one investigation by the New Yorker magazine. It turned up a 24-year-old who had authored or edited 16,000 Wikipedia entries! The subjects ranged far and wide — beyond what could be expected of any normal expert. What’s more, this man had lied about his background and expertise. When confronted with this information, Seife reported, Wikipedia’s founder seemed unconcerned. In fact, Wikipedia should have been scandalized. Facts are not like rubber — stretchy and bendable. A good source should be solidly accurate and trustworthy.

Your toolbox

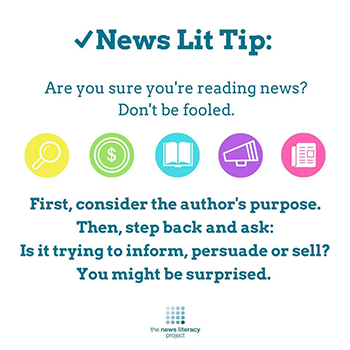

Now you understand why it’s so important to be news literate. If you’re going to share a story on social media, it’s even more important to use the skills journalists use. Sharing stories that aren’t credible is like polluting the air, says Peter Adams. He works for the News Literacy Project in Chicago, Ill. He says sharing stories that aren’t reliable is also irresponsible, like drunk driving.

Here are some tools you can use to put any story you see to the test. (Younger students can start with just the first one or two tools.)

1. Be a detective. Start by asking some basic questions: Is this story making me angry? Am I hoping this story is true? (Those are signs the story is trying to play into people’s confirmation bias.) Is the story, or the home page of the publication, trying to sell anything? (If so, this story really may be an ad.)

Does the story use all capital letters or a lot of exclamation points? (Those are bad signs.) Are the sources in the story identified by name? Does the story include the author’s name? Can you find the news anywhere else? (Those are good signs.)

Here is a worksheet from the News Literacy Project that you can use to answer these questions.

Then look carefully at the details, advises Frank Baker. Trained as a journalist, he lives in South Carolina and is a media-education consultant. That’s someone who helps teachers teach about news. He says to check out the website logo: Is that the real CNN logo, or one that looks a lot like it? Also, look at the URL at the top of a website. (For example, the URL abcnews.com.co is not ABC News, a legitimate news outlet, even though it looks almost the same. The real site is abcnews.com.)

2. Know your “news neighborhood,” says Baker. People should think about where they found each story they read, he says. If someone shared a story with you on social media, do you know where it was published first? Is it from a talk-radio show? A gossip site? An online newspaper?

Knowing where the story came from will help you understand what its goal is. This can change even within one publication, like a newspaper. Are you reading a news story on the front page of a newspaper? Then it’s trying to inform you. Is it a column on the editorial page? A newspaper’s editorial page is where writers share opinions, so a story here is trying to persuade you.

3. Analyze the pictures. A photo is often the first thing that draws you to a story — so don’t forget to ask critical questions about images, Baker says. Is the photo related to the news story it’s attached to? Why is it there? What was the photographer trying to communicate? What angle was the photo taken from? (When a photographer is shooting down on a subject, it tends to make the subject appear powerless, Baker says. When the camera is looking up at the person, they appear powerful.)

4. Use professional tools. If you can’t find the answers to these questions, search for your story on fact-checking sites such as Snopes.com, FactCheck.org or PolitiFact.com to see if it’s been reported as fake.

“Be skeptical, but not cynical,” says Lori Robertson, managing editor of FactCheck.org. If you’re questioning something a politician said, she suggests searching for a few key words on FactCheck.org. If you’re wondering about a meme or a story shared via social media, try Snopes. If you suspect a photo might have been manipulated, or might not show what its caption claims, do a reverse image search. This will show you where the image has appeared before. (To do a reverse image search, click on the camera icon in Google Images and enter the URL for the photo.)

Of course, it only takes a second to share a story on Facebook. Going through all these steps will take a lot longer. But the more you practice these tools, the more they will become habit.

You can think about that quick, thoughtless share on Facebook like fast food: easy and unhealthy. The opposite of fast food is a movement called “slow food,” which encourages farming and traditional cooking techniques. These practices take longer but are better for people and the environment.

Spikes compares the process of telling fact from fiction on the internet to the slow food movement. He calls being a responsible news consumer part of the “slow information movement.” It means taking time to step back before jumping to a conclusion. And the results should make us all a little healthier.