Faking out whales

Decoy can lure sperm whales away from fishermen’s lines

A sperm whale keeps close tabs on a longline fishing boat.

Courtesy of SEASWAP (NOAA permit #14122)

By Liz Devitt

SAN FRANCISCO, Calif. — In many parts of the world, people take boats to go whale watching. In places like the Gulf of Alaska, it can work the other way. There, sperm whales often go “boat watching” and follow fishermen. The clever mammals have learned to snatch black cod off longlines before crews can haul their catch of fish out of water. To stop these “lunch line” raids, a group of commercial fishers teamed up with scientists to find ways to keep their catch. They described how to distract whales, without harm, this week. Their tool: Noise.

Hahlen Behnken, 14, spends plenty of time on his family’s fishing vessel, the Woodstock, out of Sitka, Alaska. “On one trip last year,” he recalls, “we hauled up a three-mile longline that usually would have 300 fish on it.” But the whales beat the crew to their catch. “We had so many whales on us that we only got four fish,” the teen says.

Such big raids are unusual. The whales usually pick off about 10 to 20 percent of the catch. But the whales teach each other to do this. So the losses keep adding up. Plus, it can be dangerous to have bus-sized creatures so close to a 12-meter (40-foot) boat, says Hahlen’s mother, Linda Behnken. She’s the executive director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association, whose members worked with the scientists.

The idea for building a decoy came from fishermen who teamed up with the Southeast Alaska Sperm Whale Avoidance Project (SEASWAP). This group was founded in 2003 by Victoria O’Connell. She’s now the research director of the Sitka Sound Science Center. Jan Straley, a marine biologist at the University of Alaska Southeast, in Sitka, is the project’s cofounder.

An acoustic decoy makes sounds that lure whales to a site far from where the fishermen will bring up their lines. But as everyone soon learned, it’s not easy to fake out a whale.

First, the researchers needed to know which sperm whales raided the longlines. Their raids are known as depredation (DEH-preh-DAY-shun). And not all sperm whales do this. Working together, the fishers and researchers catalogued about 120 whales. Ten proved to be “serial depredators.” They looted the lines frequently.

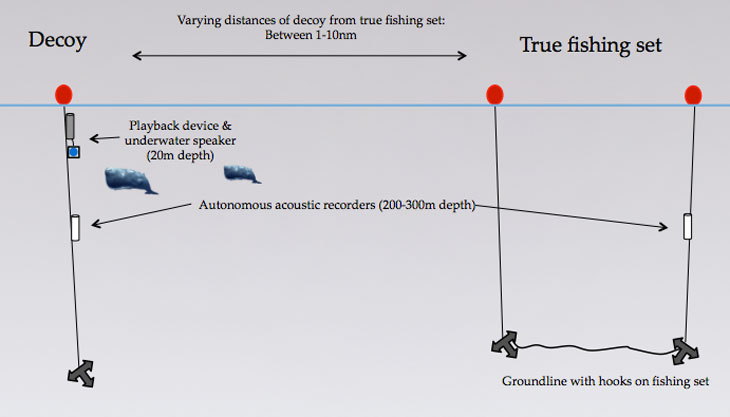

The researchers recorded the sound and used a sturdy speaker to play it underwater. Boat skippers anchored this sound decoy to a buoy some distance away from the true fishing site. Before it was time to haul up their fish — if all went as planned — the fishing crews would turn on the decoy with a remote control and the whales would swim toward the false dinner bell.

Over the course of a two-month fishing trip, one boat skipper ran 28 test hauls. Before each run, he dropped off the decoy and then moved 1.8 to 14 kilometers (1 to almost 9 miles) away to place his longlines. Roughly an hour before hauling up the fish, he’d turn on the false engine sounds.

At the same time, underwater recorders “listened” for the classic clicking sounds made by sperm whales. To show the decoy worked, there had to be whale activity in the area before the trial started, and then clicking sounds at the decoy — not the boat — as the catch was being hauled up.

During half of the trials, 14 in all, the tests went smoothly enough to analyze the whale behavior. And these trials showed the decoys could let the fishermen work in peace.

“There’s a long history of using aversive noise with marine animals to drive them away from places,” said Brandon Southall. He’s an ocean acoustics expert. Southall, who runs a consulting firm, called SEA, Inc. in Santa Cruz, Calif., was not part of the study. “This is an unusual approach,” he says.

The new decoy system is more suited to some situations than other, notes Lauren Wild, a scientist with SEASWAP. She presented her team’s work, here, at the Society of Marine Mammalogy meeting on December 16. Whales might turn back to feast at the real boat, for instance, if the decoy wasn’t at least 6 kilometers (about 4 miles) away. Also, it didn’t make sense to set off the decoy sound when other boats were around, making the same noise the decoy would have. And if whales weren’t already spotted, why send out an invite?

“It may not be ideal in all scenarios,” says Wild, “But this decoy gives fishermen another practical tool for their belt.”

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

acoustics (adj. acoustic) The science of sounds and hearing.

aversive Something negative that makes you turn away or want to flee.

buoy A floating device anchored to the bottom of a body of water. A buoy may mark channels, warn of dangers or carry instruments to measure the environment.

commercial (in research and economics) An adjective for something that is ready for sale or already being sold. Commercial goods are those caught or produced for others, and not solely for personal consumption.

decoy A device to draw attention away from something else.

depredate To raid or attack. For instance, sperm whales attack the longlines and take the fish.

longline fishing A way to catch fish that live near the ocean floor, such as halibut, black cod (also known as sablefish) and rockfish. Commercial fishers anchor to the bottom of the ocean floor “groundlines” that are up to a few kilometers (miles) long. A series of shorter, 0.3 meter (foot) long lines with baited hooks are attached to the groundlines. Buoys attached to the groundlines and floating on top of the water mark where the underwater lines sit so that fishers can find and haul them back into the boat after fish have had enough time to get hooked.

mammal A warm-blooded animal distinguished by the possession of hair or fur, the secretion of milk by females for feeding the young, and (typically) the bearing of live young.

marine Having to do with the ocean world or environment.

marine biologist A scientist who studies creatures that live in ocean water, from bacteria and shellfish to kelp and whales.

sperm whale A species of enormous whale with small eyes and a small jaw in a squarish head that takes up 40 percent of its body. Their bodies can span 13 to 18 meters (43 to 60 feet), with adult males being at the bigger end of that range. These are the deepest diving of marine mammals, reaching depths of 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) or more. They can stay below the water for up to an hour at a time in search of food, mostly giant squids.