In a first, astronomers spot the aftermath of an exoplanet smashup

Two Neptune-sized planets orbiting a distant star appear to have vaporized each other

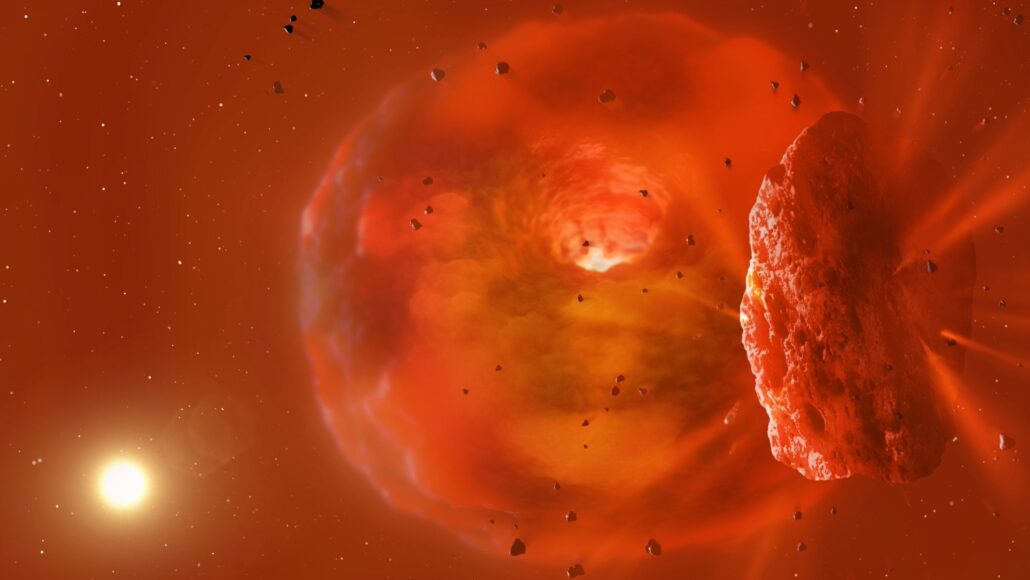

The collision of two exoplanets appears to have left behind a donut-shaped cloud of vaporized rock and water (illustrated). Such a plume would seem to explain an infrared glow visible to telescopes.

Mark Garlick

By Elise Cutts

Astronomers may have just spotted two planets smack into and vaporize each other. This smashup took place some 1,800 light-years from Earth.

Telescopes saw a surge of infrared light emerge from a star at that distance. The light appears to come from a glowing blob of broken-up planet. Debris surrounding the star would also explain why visible light from the star later dimmed.

Researchers reported these findings October 11 in Nature.

Scientists had glimpsed planetary debris around other stars before. But until now, no one has seen the smoldering remains of a collision between exoplanets.

“The possible detection” of the remains of colliding distant planets “is really exciting,” says Philip Carter. “As far as I’m aware,” he says, “no one’s claimed this before.” An astrophysicist, Carter works at the University of Bristol in England. He did not take part in the new study.

Scientific serendipity

Detecting the aftermath of this cosmic smackdown involved more than a little luck.

Matthew Kenworthy, who made the discovery, wasn’t hunting for giant impacts. “I was looking for rings” around exoplanets, he says. Kenworthy is an astronomer at Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands.

He scoured telescope data for stars that flicker or dim in strange ways. Such flickering could happen when rings block out light from a star.

He found what he was looking for in data from the ASAS-SN survey. (This is an ongoing project where telescopes watch the sky for exploding stars.) That survey had captured visible light from a sunlike star called ASASSN-21qj. The star’s visible light dimmed repeatedly. “I immediately jumped on it,” Kenworthy says.

While studying the varying light, he stumbled upon another clue. This one came through social media. Kenworthy had posted on Twitter (now called X) about ASASSN-21qj’s weird dimming. That post caught the eye of citizen scientist Arttu Sainio.

“I tweeted out saying: ‘Oh, this is amazing. This star is fading!’” Kenworthy says. “Then he added: ‘By the way, did you realize the star had brightened up [in infrared]?’”

Sainio pointed to data from NASA’s WISE telescope. It orbits Earth. WISE had tracked infrared light from ASASSN-21qj. Those data showed a strong uptick in this light about 900 days before the star’s visible light started dimming.

Kenworthy’s team had hoped to spot exoplanet rings. They didn’t. But they may have found something just as cool.

“It just totally changed the story,” Kenworthy now says.

Explaining the data

The researchers realized that a single event — the collision of two Neptune-sized planets — could have caused both the infrared glow and dimming of the star’s visible light.

Those worlds would have vaporized each other on impact. And this would have left a donut-shaped mass of rock vapors that glowed infrared. Later, the impact debris would have smeared out around the star. And that would have blocked some of ASASSN-21qj’s visible light.

This isn’t the only possible explanation for what the team saw. Two separate events could have caused the infrared glow and visible-light dimming. Perhaps the small, rocky seeds of two young planets collided. The leftover dust might then have been warmed by starlight to glow infrared. Then, a lot of unrelated material might have passed in front of the star, dimming its visible light.

But either of those events would be rare. So both happening that close together is “really, really, really unlikely,” Kenworthy says.

What if two Neptune-sized planets did collide to make a huge blob of debris? This wreckage might one day bunch together to form a new planet. Some bits could even form moons around the new world.

That could happen within a few years. Or it might take several thousand, says Carter at Bristol. Scientists can try to predict what will happen using computer models. But “the models of these impact remnants are still in the very early stages,” he notes.

Either way, keeping an eye on this debris will give scientists a rare chance to witness — not just model — the aftermath of a planetary collision.

“You expect astronomical processes to take astronomical amounts of time. And it’s like: nope! This was very fast. This happened over just a few years,” Kenworthy says.

Now, he adds, “It’ll just be fascinating to see how it evolves over time, in the next 10 or 20 years.”