Fleets of flying robots could pollinate crops

Sticky hair lets these drones capture pollen as honeybees do

Flitting drones, like the one in this illustration, might one day stand in for bees and other insects to pollinate flowers and crops.

EIJIRO MIYAKO

Eijiro Miyako gets emotional about the decline of honeybees. These insects help pollinate both food crops and wild plants. But their numbers are shrinking worldwide. Habitat loss, disease and exposure to pesticides are some of the reasons. Miyako remembers thinking: “I need to create something to solve this problem.” And now he has.

He found the answer in an 8-year-old jar in his lab.

Miyako is a chemist at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Tsukuba, Japan. He became passionate about the loss of pollinators after watching a TV documentary. It showed him the value of pollination. It also motivated him to take action.

In 2007, he had tried to make a gel that conducts electricity. But it was “a complete failure,” he recalls. So he poured the liquid into a jar, put it in a drawer and forgot about it. Cleaning out his lab in 2015, he accidentally dropped the jar and broke it.

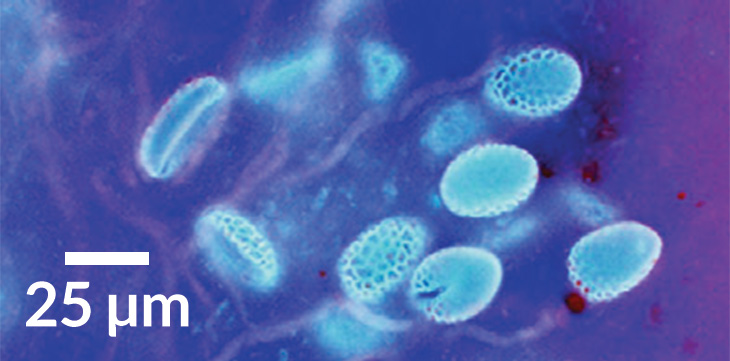

Surprisingly, the gel was still sticky. It even picked up dust from the floor. Miyako realized that the way the gel captured dust was similar to how the hairs on honeybees trap pollen. At that point, a lightbulb went off in his head. Might this be the key to artificial pollination?

To find out, he investigated whether non-pollinating insects might help him do the job. He dabbed his gel onto ants and set them loose in a box of tulips. The ants were coated with pollen after three days.

Still, Miyako worried that predators would snack on his new pollinators. After all, ants don’t have stingers to protect themselves the way that honeybees do. To give his pollinators camouflage, he mixed four more chemicals into the gel. He used compounds that change under ultraviolet light, such as the light from the sun.

This time he turned to flies. He placed a droplet of the new concoction onto their backs. Then he set the insects in front of blue paper. Under ultraviolet light, the gel changed from clear to blue, mimicking the color of the backdrop. This chemical invisibility cloak might protect insects when they’re flying against a blue sky, the chemist thought.

But Miyako wanted a pollinator that wouldn’t wander off at the first scent of a picnic. In other words, he wanted a pollinator he could control. And that’s when his mind turned to drones.

The researcher bought 10 kiwi-sized flying robots. He taught himself to fly them. It wasn’t easy. Along the way he broke all but one. Then he covered the bottom of the surviving drone with short horsehair. He used electricity to make this hair stand up. Adding his gel to the horsehair made it sticky, like bee fuzz.

Story continues below video

In tests so far, this drone has successfully pollinated Japanese lilies more than a third of the time. The drone brushes up against one flower to collect pollen, then flies into another to knock the grains off. Miyako’s team reported its results in the February 9 issue of Chem.

Miyako is glad he saved that failed gel. He thinks it is possible to create a fleet of 100 drones. With GPS and artificial intelligence, he suspects he could deploy them to join bees or other insects in pollinating flowers. “It’s not science fiction,” his tests show.