Fog Buster

A special coating can prevent misty windows and reduce screen glare.

By Sarah Webb

If you’ve worn goggles for skiing or swimming, you’ve probably been annoyed by the way they can cloud up. Or, if you’ve used a Game Boy, you might have noticed how screen glare can wipe out crucial details as you play a tricky videogame.

|

|

Goggles that fog up while you’re skiing can be a nuisance—maybe even dangerous.

|

The problems of fogging and glare don’t seem to have much in common. But materials scientists are finding that they can solve both problems at the same time. The secret is to put a coating with the right combination of chemicals and texture on the surface of the glass or plastic.

Clearing up fog

Fog forms on a mirror or window when water vapor in warm, moist air condenses to create tiny water droplets on the smooth, cool surface. Instead of letting light through, the droplets tend to scatter light in different directions. This makes it hard to see through the glass. What you do see looks blurry.

To deal with this problem, Michael Rubner considered the way droplets form on surfaces with different textures. He’s a materials scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Like many researchers who work on materials, Rubner was inspired by nature. In this case, he looked at the leaf of the Japanese lotus flower, which causes water to bead into rounded droplets (see “Inspired by Nature” and “Butterfly Wings and Waterproof Coats“).

|

|

A lotus flower and leaves with water droplets.

|

| U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

The surface of a lotus leaf is waxy and filled with tiny holes, so it looks a bit like a sponge. The waxy substances on the leaf’s surface repel water. At the same time, air trapped in the holes keeps water from sticking.

To create a coating that prevents fogging, Rubner’s idea was to replace the waxy substances with chemicals that attract water.

Making a nanosponge

To make the new anti-fog coating, Rubner and his coworkers use a material called silica. Silica consists of the elements silicon and oxygen. It’s found in most kinds of rock, and it’s the main chemical compound in sand and glass. Silica also tends to attract water molecules.

The researchers work with tiny silica particles, each one just a few nanometers wide. A nanometer is one-billionth of a meter. In comparison, a human hair is about 80,000 nanometers wide. A nanometer-sized particle is much smaller than a living cell and can be seen only by the most powerful microscopes available today.

The scientists form the coating layer by layer by dipping a glass surface into a mixture of water and silica (or glass) nanoparticles, then into a mixture containing a type of plastic, or polymer. The plastic substance acts like glue, holding the glass particles together. The final coating has as many as 20 thin, alternating layers of polymer and glass particles.

The result is a coating with lots of air pockets—like a thin “nanosponge” made of glass, Rubner says. Yet, the particles and holes are so small that the coated glass still looks and feels smooth.

When exposed to warm, moist air, the coated glass surface attracts water. Instead of beading into rounded droplets, however, the water gets sucked into the holes all over the surface. This spreads out the water, and the resulting water film doesn’t scatter light in the same way that droplets do. You can still see through the glass.

|

|

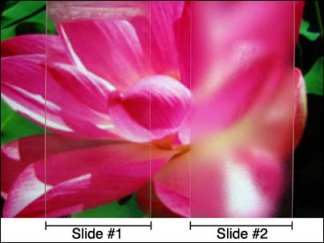

A coated glass slide (left) shows the lotus flower clearly, while an untreated slide (right) fogs the view.

|

| Rubner |

A glaring improvement

The new coating also changes the way in which light interacts with glass. Light moves very quickly, but it moves more slowly through glass than through air. Because of this mismatch, when light hits glass, some of it reflects off the surface, leading to glare.

Because of the air pockets within the spongy coating, the coated glass surface acts like a mixture of glass and air when light hits it. This combination means that almost all of the light goes through the glass. Very little light is reflected. There’s no more glare.

In addition to improving Game Boy screens, this type of coating could lead to better windows for greenhouses, Rubner says. In a greenhouse with coated glass that reduces glare and resists fogging, more light gets in, so plants have more light for growth.

Stronger coatings

A coating isn’t practical if it scratches or rubs off easily, however. To make the materials more durable, Rubner and his team heat the coatings to a high temperature, about 500 degrees C.

Heating works fine for glass, but heated plastics will melt or even burn up. So, at this point, only materials that can stand high temperatures can be coated with the new anti-fog and anti-glare film.

|

|

Although it hasn’t been done yet, constructing a greenhouse using improved glass that cuts glare and resists fogging would allow more light into the chamber.

|

| Peggy Greb, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture |

In Australia, Paul Meredith and Michael Harvey of the University of Queensland have taken a similar approach. They also use porous silica—a thin layer of glass filled with tiny holes—as a coating. But their procedure for creating the coating is somewhat different.

Meredith and Harvey have even solved the problem that Rubner and his group are still working on. Their porous silica coatings are durable on both plastic and glass. The two researchers have formed a company, called XeroCoat, to make such coatings for solar cells.

In 2 to 5 years, you might be shopping for improved eyeglasses or ski goggles or riding around in a car with a windshield that resists fogging and reduces glare. It’d be a new window on the world, thanks to materials research.

Going Deeper: