Fossil stomach reveals a dinosaur’s last meal

This armor-plated plant-eater’s stomach held mostly fern leaves and a couple of surprises

The stomach contents of Borealopelta markmitchelli reveal that it was a fern eater. But not just any ferns. Scientists found ferns belonging to only one group, so this dino may have been a rather picky eater.

Illustration by Julius Csotonyi/© Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology

A newly analyzed fossil stomach reveals what a dino had dined on shortly before it died.

The fossil guts were found inside the well-preserved fossil of a nodosaur. Known as Borealopelta markmitchelli, this plant-muncher had been covered in plates of armor. In its belly, scientists found mostly fern leaves along with small amounts of palmlike cycads and conifer needles.

This stomach is a “kind of a fossil within a fossil,” says paleontologist Caleb Brown. He works at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Canada. Brown was part of the team that reported the dino’s diet June 3 in Royal Society Open Science.

The fossil was pulled from roughly 110 million-year-old rocks in Alberta, Canada. The animal’s bones, skin, armor and horn tissue were all preserved in stone. Spanning roughly 5.5 meters (18 feet), this 1.5-ton (3,000-pound) animal is the “closest you’ll ever get to looking at what a dinosaur actually looked like,” Brown says.

Fern leaves made up roughly 85 percent of the stomach’s contents. But they belonged to only one type, Brown adds. There was a huge diversity of ferns growing in the time and place where scientists think this nodosaur had lived. So this dino “might have been reasonably picky.” He says those are data “we’ve never really had before.”

Scientists had long suspected dinosaurs chomped on ferns. This fossil now provides “some of the first hard, direct evidence” for fern-eating, says Karen Chin. She’s a paleontologist at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The fossilized guts, or cololites, are a type of trace fossil. Trace fossils also include preserved tracks, burrows and feces. Such remains can point to how ancient animals interacted with their environments. As a snapshot of the dino’s diet, the gut contents “can tell us more about dinosaur behavior,” Chin says.

Tree rings in a dino belly

Inside the animal was a squished mass the size of a soccer ball. It looked different than its surroundings. Even before their analysis, Brown and his team suspected this was a stomach. One clue: It contained spheres the size of ping pong balls. The scientists identified those as rocks that some animals swallow. The stones help squish food so a creature doesn’t have to grind up everything in its mouth.

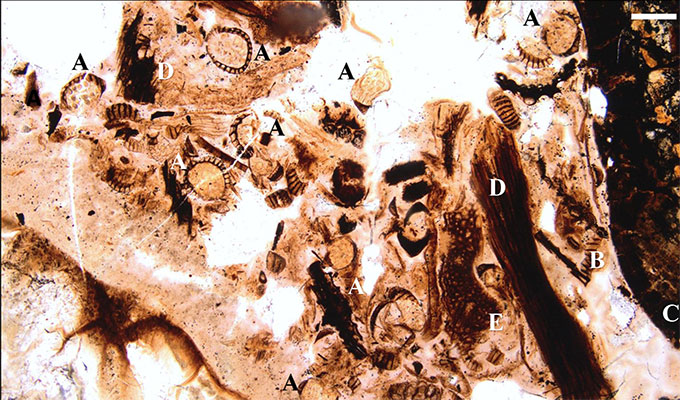

To dissect what had been eaten, the team cut thin sections of the material from around the rocks and viewed them under a microscope. Here, the scientists saw tree rings in ancient twigs. Scientists who study ancient plants and pollen helped identify other plant features. These included the cells that surround pores on plant leaves. They also saw saclike structures that hold fern spores.

To its surprise, the team also found charcoal in the stomach. “The only explanation,” says Brown, “is that the animal was foraging in a place that had recently had a forest fire.” That fire might have charred the area some six months to two years before this meal.

These microscope images show plant structures identified by scientists. They include sac-like structures that hold fern spores (A), parts of leaves that contain pores (B), woody material (D) and cross-sections of leaves (E). The parts of the photo marked “C” are stones swallowed by the animal.© Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology

These microscope images show plant structures identified by scientists. They include sac-like structures that hold fern spores (A), parts of leaves that contain pores (B), woody material (D) and cross-sections of leaves (E). The parts of the photo marked “C” are stones swallowed by the animal.© Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology

This rare fossil reveals a lot, says Victoria Arbour. “You can really start to picture this individual dinosaur’s life story. It’s not just any dinosaur. It’s got a very specific story behind it.” Arbour works as a paleontologist at the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, Canada. She was not a part of the new study.

The findings suggest the nodosaur had roamed across a coastal plain with forests full of trees, Brown says. But that’s not where it was buried, however. At some point, perhaps soon after its death, it was washed to sea. There it sank and was swiftly buried in fine sediment.

“That’s one of the reasons why it’s so well preserved,” Brown says. The stomach’s clues, such as the twig growth rings, suggest the dino’s last supper took place at the start of the growing season. That’s when things were wet. With rains and storms, a river flood might have swept the dino’s body out to sea.

From the bellies of beasts

Some of the data that scientists have about dinosaur diets comes from coprolites. These are fossils of feces. They might contain leaves or bones. Their size can also say something about who had pooped them out. But coprolites aren’t usually found right next to the dinosaur that made them. That can make it hard to match them to specific species, Arbour says.

Scientists also have studied teeth and the functioning of jaws to puzzle out what dinosaurs likely ate. The new fossil confirms some of those findings using a different line of evidence, Arbour notes. “It’s a really good example,” she says, of “how science works in paleontology.”

Paleontologists seldom get a glimpse of an animal’s innards. “All the soft parts tend to rot and get eaten by bacteria or eaten by other animals,” Arbour explains. So cololites are rare.

And of those previously discovered, many are disputed or contain leaf matter that is difficult to identify. “Up to now, I think [these have] mainly been things washing up together,” says Carole Gee. She’s a paleontologist at the University of Bonn in Germany. Dinosaurs may die and get buried along with nearby plants. This can make it look as though the plants were in the dino’s gut. But for this nodosaur, the cololite “looks pretty authentic,” she says. It offers “an excellent picture of what this dinosaur ate.”