Four summer camps show how to limit COVID-19 outbreak

These Maine facilities relied on testing and grouping of kids into ‘bubbles’

Wearing masks, grouping kids as ‘bubbles’ and social distancing all helped to protect more than 1,000 kids and staff from coronavirus infections at camps in Maine this past summer.

Jupiterimages/Creatas/Getty Images Plus

As the new coronavirus hammered U.S. communities over the summer, four overnight camps in Maine successfully kept infection rates to nearly zero.

Of 1,022 people at the camps — including campers and staff — just three people tested positive for COVID-19. Camp attendees came to Maine from 41 U.S. states, Puerto Rico, Bermuda and five other countries. But infection rates stayed low, a new study finds. Clearly, it concludes, these people closely followed public-health guidelines. And this limited the virus’s spread.

These four camps achieved what a summer camp in Georgia couldn’t. The Georgia overnight camp had to quickly close after at least 260 of its 597 campers and staff tested positive for COVID-19.

Laura Blaisdell is a pediatrician at Maine Medical Center Research Institute in Scarboro. She headed a team that describes the Maine camps’ experiences in the September 4 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. A second new study reports similar success this summer at child-care facilities in Rhode Island.

These new successes could point to how places like schools might safely reopen with in-person classes during the ongoing pandemic.

The importance of camp ‘bubbles’

The Maine camps prevented outbreaks by relying on a mix of different measures. These included testing, social distancing, masks and isolation. But one of the biggest impacts may have come from its use of social bubbles.

Bubbles refers to a new practice of allowing close contact only between people in small, well-defined groups. Each group is a “bubble.” If one member later tests positive, then only the rest of the bubble must be isolated for the period it takes the virus to show up in newly infected people.

At the Maine camps, the bubbles ranged in size from five to 44 people. Each bubble became like a family during the camp, Blaisdell’s team reports. No one could interact with anyone outside their bubble unless they wore a mask and practiced social distancing. The bubbles gave kids “the ability to have a family unit at camp,” Blaisdell explains.

Officials told all 642 children and 380 staff members to quarantine at home for 10 to 14 days before camp. Everyone also got tested for COVID-19 five to seven days prior arriving. (The only exception was for 12 people who had already gotten COVID-19.)

Four people who tested positive for the virus stayed in isolation at home for 10 days before heading off to one of the camps. Once at camp, kids and staff were checked daily for symptoms. To further limit any chance of virus spread, most camp activities took place outdoors.

Two staff members and one camper from three different camps tested positive while at camp. None of them showed symptoms. Their bubbles were isolated for two weeks, but still “were able to have a camp experience,” Blaisdell says. They still could have fun and play together

The three positive cases never spread the virus to anyone else. Each remained isolated until they tested negative for the virus twice.

Repeated testing turned up potential spreaders of the virus. Bubbling allowed officials to then identify campers most at risk of catching the virus. Bubbles proved “an unsung hero,” Blaisdell now says.

Lessons for schools?

While bubbles, social distancing and masks can each help reduce coronavirus spread to some extent, combining helps even more.

Every public-health measure to limit the spread of a virus “is like a layer of Swiss cheese,” Blaisdell says. It has a hole in it. It’s the stacking of “multiple layers of cheese on top of each other that close those holes,” she says. That, she says, is what really limited the spread of infection.

By contrast, the Georgia summer camp that had the big outbreak did not require its campers to wear masks. And though its campers had to show proof of a negative COVID-19 test before arriving, they were not tested again once they got to camp.

The Maine camps may offer lessons for schools on how to limit spread of the virus. At the four camps in Maine, staffers who went home every day had to wear masks whenever at camp. They also had to keep a social distance from other attendees. It likely helped, too, that rates of COVID-19 infections in Maine were quite low while the camps were running.

Experts also point to some differences from schools. Creating fairly virus-free bubbles might be much easier in summer camps. Why? Most people in schools come and go throughout the day, and then end up at home each night. So they may have more interaction with others — from family and people on their commutes to people at a grocery or drug store.

The camps also were not too large. Some schools have thousands of students and staff. The more people in a school, the harder it can be to make sure that everyone is following the necessary mix of public-health measures.

“If you follow the rules, then this can absolutely be successful,” says Brian Nichols. He’s a virologist at Seton Hall University in South Orange, N.J. But, he adds, “when you scale it up [to bigger schools], you just have to plan on the fact that some people aren’t going to follow the rules.”

Off to camp

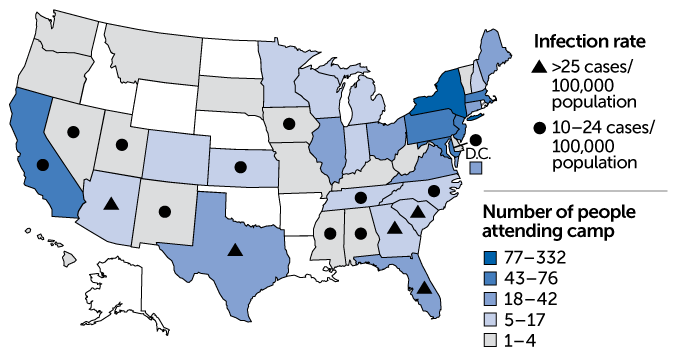

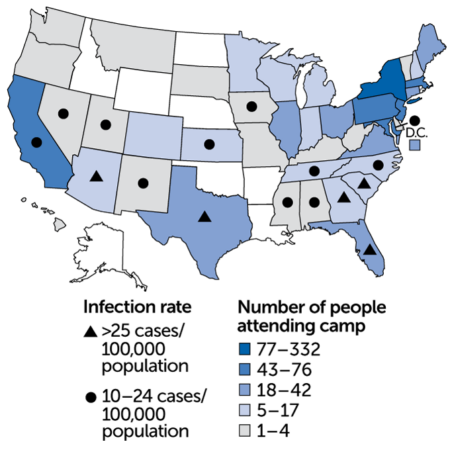

More than 1,000 people from 41 U.S. states and elsewhere attended four Maine summer camps between mid-June to mid-August. This map shows from which states campers and staff members came. (No one came from states colored white.) Many people traveled from states like Texas and Florida that were hit hard by COVID-19 (seven-day daily average rate of coronavirus infection as calculated on July 1, shown). Still, the camps’ public-health measures prevented outbreaks. (Infection rates are not shown for states with fewer than 10 cases per 100,000 population.)

Camp population, by home state, and states’ COVID-19 infection rates