Full-body taste

Turns out that the tongue isn’t the only place where the body can taste what you ate

People assume that our sense of taste comes from how foods interact with the tongue. But taste-sensing cells aren’t restricted to the tongue. They even help the brain make sense of materials in the nose, lungs and gut.

gpointstudio/iStockphoto

By Douglas Fox

It was an exciting day when Thomas Finger looked inside the nose of a small black mouse. Finger had borrowed the animal from another scientist. It was not your average mouse.

The mouse’s genes had been changed so that the taste buds on its tongue turned green when you shined light on them — like a secret message written in secret ink.

But no one had ever looked inside its nose. When Finger finally did look there with a microscope, he saw thousands of green cells dotting the soft pink lining. “It was like looking at little green stars at night,” says Finger, who is a neurobiologist at the Rocky Mountain Taste and Smell Center at the University of Colorado in Denver. (A neurobiologist studies how the nervous system develops and functions.)

Seeing that green starry sky was Finger’s first glimpse of a new world. If he and other scientists are right, we don’t taste things just on our tongues. Other parts of our body can also taste things — our nose, our stomach, even our lungs!

You might think of taste as something that you experience when you put chocolate in your mouth — or chicken soup, or salt. But for you to taste chocolate or chicken soup, special cells on your tongue have to tell the brain that they detected chemicals that are in the food. We have at least five kinds of these chemical-detecting cells (commonly called taste cells) on our tongues: cells that detect salt, sweet compounds, sour things, bitter things and savory things like meat or broth.

You might call these five things the primary colors of your mouth. The unique taste of every food is made up of some combination of salt, sweet, sour, bitter or savory, just as you can make any color of paint by mixing together bits of red, yellow and blue.

It’s these chemical-sensing cells that scientists are now finding all over the body.

“I’ll bet you that in terms of total number of cells,” says Finger, “there are more [taste cells] outside the mouth than inside the mouth.”

This gives us clues about other functions the sense of taste has in our bodies. It could also help scientists find new treatments for certain diseases.

Fish skin: more than a feeling

It’s an exciting time for scientists who study taste. Finger spent 30 years working toward this big moment. Some of the first clues came from fish.

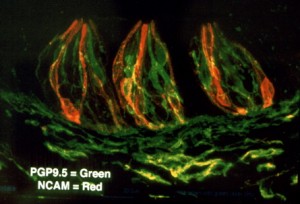

Pictured are three taste buds on the tongue of a mouse. Each one is half as wide as a grain of salt. Taste cells, which appear here as red and green, bunch together to form the taste buds. The red cells taste sour things. It’s not clear yet what the green cells taste

Back in the 1960s, scientists looking at fish skin under microscopes discovered that the outside of a fish’s slippery body is dotted with thousands of funny cells shaped like bowling pins. Those funny cells look just like the chemical-detecting cells on your tongue. At the time, no one was sure what those bowling-pin cells on fish skin did. But years later, scientists found that they actually can taste. When food chemicals were sprinkled onto the fish skin, those cells sent a message to the fish brain — just like the cells on your tongue tell your brain when you taste food.

For fish, being able to taste things all over their body comes in handy. Some fish called searobins use this to find their next meal. When searobins poke their pointy fins into the mud on the seafloor, they can “taste” the worms they’re looking to eat. Other fish called rocklings use these cells to sense the presence of larger fish that might want to eat them.

In these cases, the buried worms and big fish leak small amounts of chemicals into the water and mud. Taste cells on the skin of searobins and rocklings detect the chemicals (sort of the way you might be able to taste what’s in the bathwater after your filthy little brother sat in the tub for a while).

As Finger studied searobins, goldfish and other wet critters, he began to wonder whether land animals like cats, mice and people could also sense taste outside of their tongues. “Why wouldn’t it be a good idea?” he asks. “The more information you get from your environment, the better off you are.”

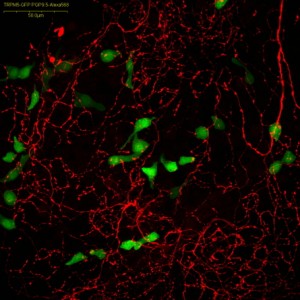

Nosey tasters: Taste cells on the inside of the nose of a genetically engineered mouse appear green under the microscope. Those taste cells talk to the treelike branches of nerve cells, which are red in this picture.

Peeling mud

But finding taste cells on land animals wasn’t easy. Unlike fishes’, their skin is covered in a dry crust of dead cells, like the layer of cracked mud that forms as a water puddle dries. A taste cell hidden under that crust wouldn’t function. It needs to come into contact with chemicals in the outside world in order to detect them. So Finger decided to look at the wetter, fishier parts of our body. He started his search deep inside the nose.

That’s when he borrowed the mouse with the green taste buds — and found those green, bowling pin-shaped cells inside its nose. The cells were scattered instead of being clumped together, as they are in the tongue. But one thing was for sure: Those cells could taste.

When Finger tested them, the cells contained the same special proteins, called receptors, that your tongue uses to detect chemicals in food. Different kinds of receptors detect different kinds of chemicals — like sugars, sour things and so on. Those in the mouse’s nose specialized in detecting bitter chemicals.

Since Finger’s discovery of this in 2003, other scientists have found bitter-sensing taste cells inside the hundreds of branching tunnels that move air through the lungs of animals.

Some scientists have also found taste cells along the path that food travels through a person’s body — a journey of at least 12 hours. From the stomach, where food is first digested, those taste cells can be found all of the way to the large intestine at the lower end. Some in your gut taste bitter things, others scout for sweet sugars.

(Not) tasting your poop

“There is an enormous number of these cells in the lower gut,” notes Enrique Rozengurt, a biologist at UCLA (the University of California campus in Los Angeles) whose team first found taste cells in the gut in 2002. “Why do you have all of these receptors?” asks Rozengurt. “There are some very profound possibilities.”

It might seem like a really bad idea to have taste cells beyond the tongue. In your nose, wouldn’t you taste salty buggers? And wouldn’t you also taste the brown gooey stuff in your large intestine — which is pretty much just poop waiting to be excreted? If we have taste cells inside our body, shouldn’t we be tasting nasty stuff all day long?

No, says Finger. What you experience when your body “tastes” something depends on what part of your brain the taste cells are talking to.

When you put a bitter pill in your mouth, the cells on your tongue talk to a part of your brain called the insular cortex. This part of your brain is part of your moment-to-moment thoughts. It gets the message from your tongue — bitter! And yuck! Immediately, your face scrunches up. You want to spit the pill out.

Your inner worm

But when cells in the gut detect something bitter, they send a little telegram to a deeper, older part of the brain. Scientists call it the nucleus of the solitary tract, but you might well think of it as your inner worm.

This part of the brain takes care of simple things that a mindless worm would do: pushing food through the gut, digesting it and pooping it out. You don’t have to think about those things. They just happen.

When your brain’s inner worm senses the arrival of something bitter in the intestines, it tells your brain: Stop. You’ve eaten something bad. Get rid of it — quickly! You may suddenly feel sick, throw up, or have diarrhea. And these things happen without any conscious decisionmaking on your part.

The world is full of bad things like poisonous plants and spoiled foods. These are things that bitter-taste cells in your digestive system scout for. Says Rozengurt, they “are there to defend us against all of these harmful substances.”

Bitter sneeze

Bitter-detection cells in your nose and lungs protect you in kind of the same way. Bad bacteria sometimes enter your nose or lungs.They cause infections that can make it hard to breathe. Bitter-taste cells sound an internal alarm when they detect chemicals that the bad bacteria squirt out.

That alarm signals your body to sneeze or cough the bad stuff out. Bitter-taste cells can also trigger a process that tells white blood cells to attack the unwelcome germs.

It makes sense that you’d want to get rid of nasty, bitter-tasting stuff. But your stomach and intestines also have cells that detect sweet sugars. And they send out very different messages.

It’s one thing to taste sugary pancakes and syrup in your mouth, but what about along the rest of the 30 feet that your breakfast travels through the stomach and intestines?

Those other parts of your body also need to know when something sweet has arrived, says Robert Margolskee of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Cells scattered up and down your gut act as a tracking system to let your body know when the sugary food arrives at each location. “It starts things going further down in the digestive tract to digest those things,” says Margolskee.

Scientists have some evidence that the gut also contains taste cells that detect meaty, savory chemicals. Like the sweet-taste cells, these probably also alert different parts of the gut to what’s coming.

Taste medicines

Margolskee lent Finger those green-tongued mice in 2001. In 2009, Margolskee discovered that sugar-detecting cells of the intestine squirt out a messenger substance, called a hormone, that prepares the intestine to soak up sugars. Those hormones also let another part of the body, called the pancreas, know that sugar is on its way. The pancreas oozes out its own hormone — called insulin — that tells other parts of the body, from the muscles to the brain, to prepare for that sugar.

Making drugs that affect the gut’s taste cells could help treat a common disease called diabetes. In diabetes, the rest of the body appears almost deaf to the insulin message that the pancreas sends out. So the muscles and brain don’t take in much of the sugar, a major source of energy, from the blood. A drug that “turns up the sound in these gut taste cells,” says Margolskee, might help the gut and the pancreas more effectively shout out to the rest of the body that sugar is coming — and to get ready.

Some people have another problem called irritable bowel syndrome. Here, food oozes through their intestines too quickly or too slowly, causing painful traffic jams. Drugs that tickle the bitter-detecting cells might help the intestine push food through more quickly and smoothly, reducing belly aches.

Just this past November, scientists made a more surprising discovery: Bitter-tasting cells in the lungs might one day help doctors treat a disease called asthma.

People with asthma have trouble breathing because the airways in their lungs close up. Now scientists have found that some bitter substances actually open those airways. And these substances do it better than one medicine that doctors frequently use to treat asthma.

It’s was only the latest surprise. People who study taste outside the mouth expect more will keep on coming.

Until recently, says Rozengurt, a universe of taste sensors existed “that we were vaguely aware of, but we didn’t have any clues of how to study. Now we do.”