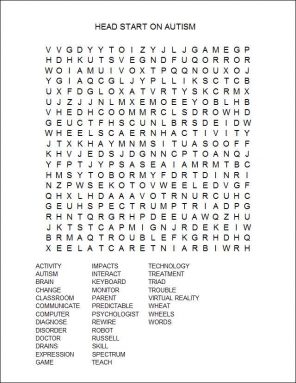

Getting a head start on autism

New research points to effective early therapies for a surprisingly common brain disorder

Researchers at Vanderbilt University have designed Russell the robot (background). It helps teach kids with autism, like this young boy, how to imitate people and to interact with them.

Vanderbilt University

By Bryn Nelson

This is the second of a two-part series on autism spectrum disorders.

When Matthew Shumaker was diagnosed with autism in the early 1990s, his parents didn’t know anyone else who had a child with the brain disorder.

How times have changed.

On March 27, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the CDC for short, delivered surprising news: Autism is far more common than people once thought. The disorder, which disrupts how the brain develops, may now impact as many as one in 68 kids across the United States. That number is nearly 30 percent higher than just two years ago. At that time, the CDC estimated one in 88 kids might be affected. The new number means that about 1.2 million children under the age of 18 may be autistic.

Instead of a single disorder, researchers often use the term “autism spectrum disorders” to refer to a group of closely related disabilities. Some affected children may have trouble interacting with or looking at other people. Instead, they may focus on objects. Matthew, for instance, seldom played with other kids. But when he was little he was fascinated with wheels and lights. He also loved drains — the type found at the bottom of sinks and drinking fountains. (In fact, he once asked Santa to bring him a drain for Christmas.)

No one knows why autism seems to be getting more common. One possible reason is that doctors are getting better at spotting the signs of trouble. New research, in fact, suggests that doctors may be able to diagnose autism earlier in life than previously thought.

These studies “are really interesting and really promising,” says Zachary Warren. A psychologist, Warren is the director of a major autism institute known as TRIAD at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. (TRIAD stands for Treatment and Research Institute for Autism Spectrum Disorders.) Diagnosing autism earlier, Warren says, means that children also can be treated much sooner. And researchers have known for more than a decade that the earlier a child is treated, the better.

Finding a treatment that works

In her book, A Regular Guy: Growing Up with Autism, Laura Shumaker writes that after her son Matthew was diagnosed, the family doctor didn’t know how to help him. “When Matthew was young, I raced around and tried all of these freaky therapies,” she says. Desperate to help him, she even changed his diet so that he didn’t eat any more milk or wheat. She had heard from other parents that the change might make him better. It didn’t.

The Shumakers finally figured out that Matthew might need a play therapist: someone who could play with him and relate to him. Recent studies suggest they made the right decision.

One of the best treatments for autism involves one-on-one sessions between the child and a trained teacher, parent or doctor, says Kathy Angkustsiri. She’s a doctor and autism expert who studies child development and behavior at a research center at the University of California, Davis. It’s called the MIND Institute (which stands for Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders.)

The sessions can seem like play. But there’s really more to it. “It’s about how to teach that child to make eye contact with other people, how to respond to his or her name and how to focus attention more on people than on objects,” Angkustsiri says.

Researchers at the MIND Institute and several other universities tried this treatment on children who were just 18 months to 30 months old. The scientists then monitored the brain activity of the kids as they looked at pictures of a person’s face. The experts saw big changes: The brain activity looked more like what occurs in a typical child. This suggests the treatment might help “rewire” parts of the brain that hadn’t been connecting properly.

Scientists are encouraged by these results. They suggest that some effects of autism can be reduced or even reversed if they are treated early enough in life.

Learning from robots

One of the most important parts of any treatment is teaching kids with autism how to communicate with other people. “When we think about communication, the first thing that usually pops into our mind is words, right? Because that’s how you and I really interact with each other now,” Warren says during an interview. For very young children, though, learning how to communicate means mastering certain basic skills. One of them is paying attention to what someone else is looking at or doing. Another is copying that person’s behavior and actions.

“If you and I are both looking at a toy and you start labeling that toy with a word, I’m more likely to learn what that toy is and to use that word,” Warren explains. Kids with autism, however, often have trouble looking at someone else or imitating them. As a result, he points out, it can prove harder to teach kids with autism how to communicate.

Laura Shumaker recalls saying Matthew’s name when he was younger. “He would just kind of look around, but not at me,” she says. After years of therapy, however, he learned how to look her in the eye and talk, joke and laugh with her.

To help kids with autism build their communication skills, Warren and other researchers at Vanderbilt have built a specialized system around a small humanoid robot nicknamed Russell.

“Hello, I want to play with you,” Russell says to each child.

This robot is hooked up to a video-game system called Microsoft Kinect. The modified system can detect a child’s movement and gestures. The robot then uses that information to craft follow-up messages. For instance, Russell might ask a child to raise her arms. It then can detect whether she does so, and praise her. But if the girl raises her hands only part of the way, Russell might encourage her to reach a little higher.

Some children with autism who don’t respond to their parents or other adults will pay close attention to the robot, Warren has found. Many research groups, in fact, find that kids with autism seem to prefer interacting with computers and other technology. No one knows exactly why. But some scientists think these kids relate better to computers because they are more predictable.

Many researchers have begun using robots, video games, iPads and other devices to help kids with autism learn and communicate. Russell the robot, for example, can point out an object in another part of a room —and also determine whether a child looks in that direction. Eventually, Warren hopes that the robot might help teach kids the skills they’ll need to interact with people, too.

Some scientists are using video games to teach children with autism how to both read facial expressions and interact with others. When children pay attention to the right details or signals, the interactive games reward them by letting them move on to the next level.

Help from virtual reality — and other tech

At the Davis MIND Institute, researchers are using another technology, called virtual reality. This computer-based system can make it seem like a child is in the middle of a busy classroom, for example. With it, “kids wear a headset and ‘see’ other kids in the classroom. It’s kind of like a safe space to practice social skills,” Angkustsiri says.

Such technology can help guide kids through tricky social situations like those they might encounter at school.

In some cases, technology has given kids with autism a life-changing way to communicate. One girl living with autism, teenager Carly Fleischmann, cannot speak. “Autism has locked me inside a body I cannot control,” she has written. But one day when she was 10, she had a breakthrough. She felt sick and spelled out the first words she had ever used to reach out to others: “HELP TEETH HURT.”

In a 2012 book that she wrote with her dad, Carly’s Voice, and in a series of videos, she describes how she has used a keyboard and other forms of technology to find her own voice. Carly now has her own blog and tens of thousands of Facebook fans and Twitter followers.

As they get older, many kids with milder forms of autism learn to focus on specific jobs or interests. Matthew Shumaker, for example, loves landscaping and singing karaoke songs such as “Born to Be Wild.” With treatment, he also has learned how to interact much better with others. Now 27, he runs a landscaping business.

“It is not easy to be Matthew, someone who wants desperately just to be a regular guy,” Laura Shumaker writes in her book. “But I admire him for trying.” With their many research projects, scientists are hoping to make that goal far easier to reach for the next generation of kids growing up with autism.

In this video, “Carly’s Café,” teen Carly Fleischmann shows how frustrating it can be to communicate but autism keeps you from being able to speak (as it does with some people). The video also shows how loud and overwhelming an ordinary coffee shop’s sounds can be to someone with this disorder. Credit: The Fleischmanns

Power Words

autism spectrum disorders A set of developmental disorders that interfere with how certain parts of the brain develop. Affected regions of the brain control how people behave, interact and communicate with others and the world around them. Autism disorders can range from being very mild to being very severe. And even a fairly mild form can limit an individual’s ability to interact socially or communicate effectively.

development (in biology) The growth of an organism from conception through adulthood, often undergoing changes in chemistry, size and sometimes even shape. When preceded by neuro, it refers to the growth and maturation of the brain.

gene A segment of DNA that contains the instructions for making a protein. Those proteins govern the behavior of a cell — or large groups of cells. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

neuro An adjective that refers to neurons, the impulse-conducting cells that make up the brain, spinal column and nervous system.

psychology The study of the human mind, especially in relation to actions and behavior. Scientists and mental-health professionals who work in this field are known as psychologists.

technology The application of scientific knowledge for practical purposes, especially in industry.

virtual reality A three-dimensional simulation of the real world that seems very realistic and allows people to interact with it. To do so, they usually wear a special helmet or glasses with sensors.