Getting ready for the solar eclipse

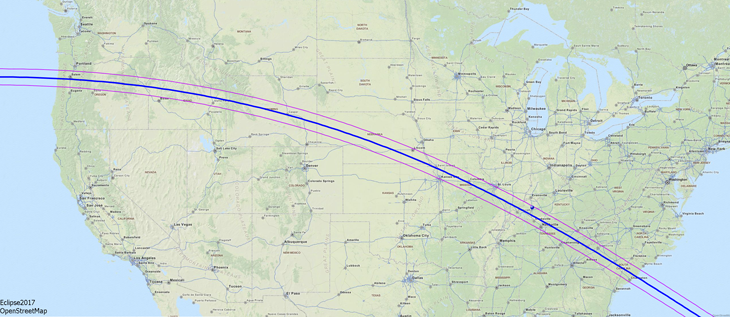

On August 21, the moon’s shadow will race from Oregon to South Carolina

On August 21, a solar eclipse will be viewable across the United States. Those who want to take a look will need eye protection, though. Looking directly at a solar eclipse without such protection can damage the eyes.

Entwicklungsknecht/iStockphoto

Eeriness creeps in. Colors change and shadows sharpen. The last minutes before a total eclipse of the sun triggers a primal reaction, says astronomer Jay Pasachoff.

“You don’t know what’s going on,” says Pasachoff. “But you know something is wrong.”

Millions of people will encounter this reaction on August 21, 2017. That’s when a total eclipse of the sun will sweep across the continental United States. This will be the first eclipse to grace the country since 1979. And it will be the first since 1918 to bring a total, if temporary, blackout coast-to-coast. Its path will be roughly 120 kilometers (75 miles) wide. Created by the moon’s shadow, this so-called totality will pass through 12 states, from Oregon to South Carolina.

Researchers and the public alike have been gearing up to make the most of this rare spectacle. After all, U.S. communities won’t get another chance until 2024.

Story continues below map.

The mystery of the eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the moon passes between the sun and our planet, casting its shadow on Earth. For someone sitting on Earth viewing the eclipse (with some kind of eye protection), it appears that the moon nearly blots out the sun. A total solar eclipse occurs about once every 18 months.

Eclipse enthusiasts will travel from all over the world to experience up to nearly three minutes of midday twilight and glimpse the sun’s corona (Koh-ROH-nah). The outer layer of the sun, it is an intensely hot, ionized gas, or plasma. During a total eclipse, this seldom-seen halo of light will frame the blacked-out sun.

At its sight, “People cheer and people cry,” Pasachoff says of Williams College in Williamstown, Mass. And he should know. He’s already witnessed 33 total solar eclipses and 30 partial ones.

People like him will often have to travel to the far ends of the Earth to experience an eclipse. That’s because eclipses that pass over densely populated portions of the planet are fairly rare. This explains why the 2017 event is so special. Millions will be able to experience it firsthand, often without leaving home.

For scientists, an eclipse offers more than an interesting experience, though. It’s a time to study the corona. Though some of it is visible all of the time to a few telescopes in space, the region where the corona meets the surface is masked by the sun’s intensity. “Only on days of eclipses can we put together a complete view of the sun,” Pasachoff explains. For researchers, the 2017 eclipse is thus another chance to connect what they see on the surface of the sun to what’s happening in the outer reaches of its corona.

One enduring mystery relates to temperatures on the sun. The sun’s surface is a relatively balmy 5,500° Celsius (nearly 10,000° Fahrenheit). But the corona is millions of degrees hotter. Scientists still aren’t really sure why. “The consensus is that the sun’s magnetic field is responsible,” says Paul Bryans. “But it’s not clear how,” he adds. Bryans works as a solar physicist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

The magnetic field in the corona is too tenuous to study directly. Instead, researchers hope one day to measure the effect of magnetism on certain wavelengths of infrared light emitted by the corona. Bryans is leading a team that will point a device called a spectrometer (Spek-TROM-eh-tur) at the sun during the eclipse to detect that light.

“The plan is to put us in the back of a trailer, drive north to Wyoming and just sit and stare at the sun,” says Bryans, for whom the 2017 eclipse will be his first. “People keep telling me it’s a terrible thing to do because I’ll be stuck in the back of the trailer.”

This experiment will test whether the corona emits light at the predicted wavelengths and, if so, how brightly. (Scientists will have to wait for improved instruments and another eclipse to see how these wavelengths are distorted by the magnetic field.) One of the advantages of a mobile observatory, Bryans says, is that the team can look at weather forecasts the day before and drive to clear skies.

Another option is to point an infrared spectrometer out the window of a Gulfstream V jet. The researchers could then cruise at an altitude of about 15 kilometers (9 miles) along the path of the eclipse and make measurements. That is what Jenna Samra will be doing. She is a physics graduate student at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Aside from getting away from weather intrusions, the flying telescope will soar above much of Earth’s water vapor, which absorbs a lot of the sun’s infrared light.

The moon’s shadow will race across the country at about 2,700 kilometers (1,700 miles) per hour. Only the world’s fastest military planes are capable of flying that fast. “We won’t be able to keep up with it,” Samra says. The jet her team uses will collide with the shadow in southwest Kentucky. “We will be able to stay in for about four minutes,” she says. That’s more than a minute longer than for anyone stuck on the ground.

Viewing the eclipse

For observers on Earth, the eclipse first touches U.S. soil at 10:16 a.m. Pacific time near Oregon’s Depoe Bay. The shadow will move through five state capitals — Salem, Ore.; Lincoln, Neb.; Jefferson City, Mo.; Nashville, Tenn.; and Columbia, S.C. It will even cross a few national parks: Grand Teton, Great Smoky Mountains and Congaree. A spot in the Shawnee National Forest (just southeast of Carbondale, Ill.) has the honor of longest time in darkness: about 2 minutes, 42 seconds. Cape Island, S.C., is the shadow’s final stop. The shadow will then leave the continent around 2:49 p.m. Eastern time, just about an hour and a half after it had entered Oregon.

Based on typical climate patterns in late August, the weather has a better chance of cooperating in the western half of the eclipse path, from Oregon to western Nebraska. That’s why Pasachoff will be setting up in Salem, Ore. He won’t be looking for elusive infrared light. Instead, he will be taking rapid-fire images of plasma loops arcing off the sun. For a brief time, they will peek out from behind the moon.

These loops are coils of ionized gas trapped in billowing magnetic fields. One idea for why the corona is so hot is that these loops subtly jiggle. That is thought to stir up the surrounding plasma and heat the corona. By looking for oscillations along the loops, Pasachoff’s team will see if this hypothesis holds up.

The sun won’t be the only thing that’s probed during the eclipse. Some researchers will be keeping an eye on Earth’s atmosphere to see how it responds to a sudden loss of sunlight. Angela Des Jardins is a solar physicist at Montana State University in Bozeman. She is leading the national Eclipse Ballooning Project. Its scientists will launch more than 100 weather balloons at various times along the path of totality. Those balloons will measure changes in such things as temperature and wind speed.

For those who can’t make it to the eclipse path, or who get stuck under cloudy skies, the ballooning project will serve up live feeds from a vantage point unlike any other. Those balloons will soar roughly 30 kilometers (18 miles) above the ground. More than 50 teams of high school and college students will launch cameras on additional balloons from 30 sites along the eclipse path. Video and photos will be transmitted as they’re taken. These will be accessible via a website.

From 30 kilometers up, “you can really see the curvature of Earth and the blackness of space,” says Des Jardins. “Seeing the shadow of the moon come across the Earth gives you an amazing perspective of what’s going on.”