Giant worms may have hidden beneath the ancient seafloor to ambush prey

Trace fossils may be evidence of predatory behavior similar to modern bobbit worms

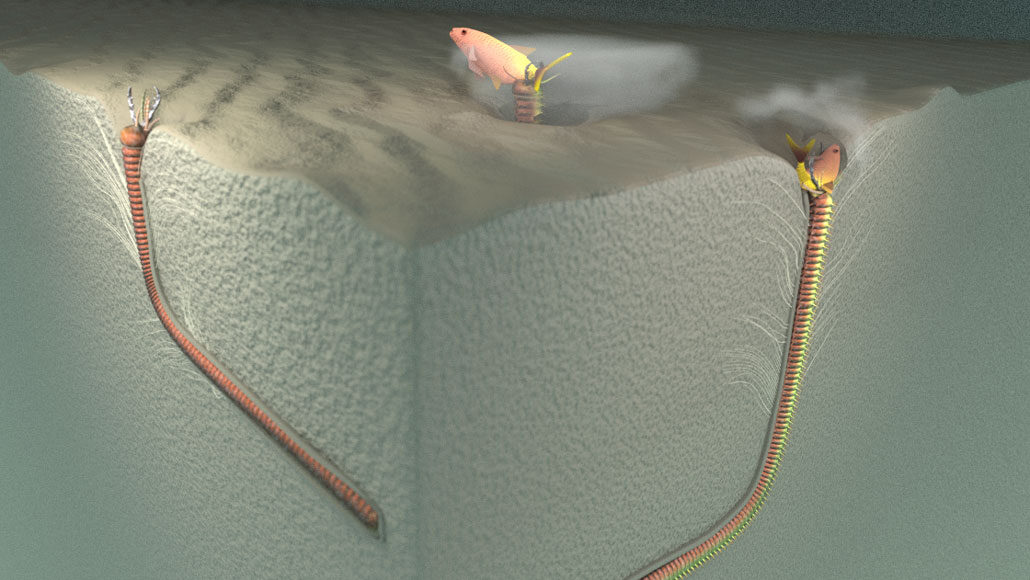

Like modern bobbit worms, ancient worms may have dug holes in the seafloor to lie in wait before attacking prey (illustrated), a new study suggests.

Y-Y. Pan et al./Scientific Reports 2021

Around 20 million years ago, giant ocean worms may have burrowed into the seafloor and burst forth like the space slug from Star Wars to ambush unsuspecting fish.

Ancient underground lairs left behind by these animals appear in rocks from coastal Taiwan. Researchers report this January 21 in Scientific Reports. The diggers may have been analogs of modern bobbit worms (Eunice aphroditois). Those worms are known for burying themselves in sand to surprise and strike their prey.

The burrows are trace fossils. This type of fossil includes things such as footprints and fossilized poop. They provide evidence of animal activity preserved in the geologic record. The newly reported fossils were first spotted in 2013. Masakazu Nara found them at Taiwan’s Badouzi promontory. Nara is a paleontologist at Kochi University in Japan. More of these fossils turned up later amid the otherworldly rock structures of Yehliu geopark. This is a popular tourist attraction in Taiwan. It was once a shallow ocean ecosystem 20 million to 22 million years ago.

From 319 fossil specimens, the team was able to reconstruct the burrows. The animals drilled L-shaped paths into the seafloor. The burrow had a funnel structure at the top. This structure looks like a feather in vertical cross sections. The burrows were about 2 meters (6.5 feet) long and 2 to 3 centimeters (about an inch) wide.

“Compared to other trace fossils, which are usually only a few tens of centimeters long, this trace fossil was huge,” says Yu-Yen Pan. She is a geologist at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada, and co-authored the study. She dubbed the trace fossil Pennichnus formosae. The name combines the Latin words for feather, footprint and beautiful.

The tunnels were most likely dug by some kind of giant worm, the researchers conclude. The tunnels lacked the hallmark pellets lining tunnels made by crustaceans. And they had smoother linings than bivalve tunnels. Iron deposits along the inside suggest the digger must have been long and slender. It probably used mucus to reinforce the walls. Funneling at the top of the burrow also points to the ancient worm emerging from its hideout, retreating and then rebuilding the top sections over and over again.

“These [funnels] suggest that the worm repeatedly dragged its prey down into the sediment,” says Ludvig Löwemark. This study coauthor is a geoscientist at National Taiwan University in Taipei.

Modern family?

These hunting tactics are consistent with those of modern bobbit worms. Those worms conceal their 3-meter-long bodies in sand. They surge forth to grab unsuspecting prey with scissor-like teeth. The oldest evidence of bobbit worms comes from the early Paleozoic Era. That’s around 400 million years ago. How or if the ancient worms relate to bobbit worms, however, is not known.

The worms that lived in these ancient tunnels were invertebrates. That means they didn’t have skeletons to leave behind in the fossil record. If soft tissue or teeth from bobbit worms were found preserved inside a burrow, that would confirm that these animals were living in the area 20 million years ago. But teeth break easily. Soft tissue degrades. Both are unlikely to turn up in the fossil record. That’s normal for trace fossils.

“It is almost always a challenge to link fossil traces to specific trace makers,” says David Rudkin. He’s an invertebrate paleontologist. He works at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada. He was not involved with this study. Still, Rudkin thinks that the case for ancient bobbit worms hiding in these burrows is convincing.

If ancient bobbit worms did terrorize the seafloor back then, their burrows are a rare example of invertebrates hunting vertebrates. Usually it’s the other way around. Their presence also makes the local ecosystem more complex than was previously thought, says Löwemark. “There was obviously a whole lot more going on at the seafloor 20 million years ago than one would imagine when seeing these sandstones,” he says.