Hack: How to spy on a 3-D printer

Smartphones can figure out what a printer makes by analyzing the noise and energy it emits

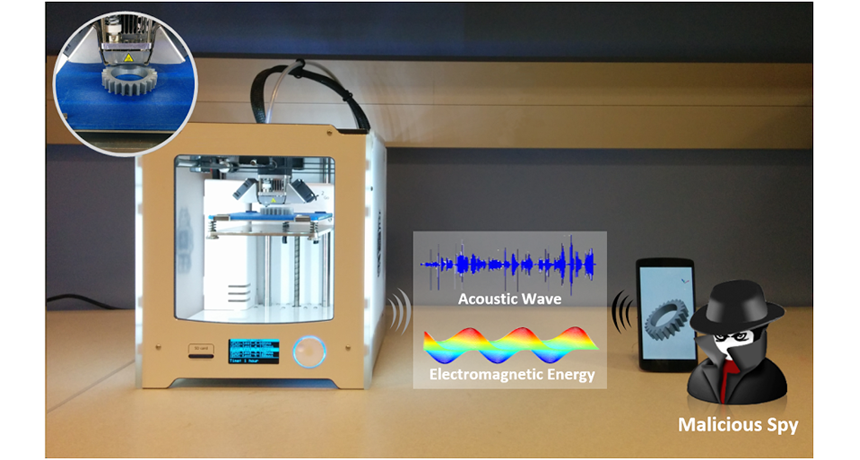

A thief with bad intentions might use a smartphone to spy on a 3-D printer. That phone would listen for the sounds (acoustic waves) and electromagnetic energy emitted by a printer while it’s working.

Wenyao Xu

Your 3-D printer is leaking, but not in ways you can see. It leaks sounds and energy. That’s not a problem — unless you want to keep your creation a secret. In that case, it’s time to get serious about security. Computer scientists have now shown that hackers can eavesdrop on 3-D printers — and then copy what they made. All it takes is your average smartphone.

As 3-D printing becomes more widespread, thieves will find new ways to steal original designs, worries Wenyao Xu. This computer scientist at the State University of New York in Buffalo led the new work. Right now, 3-D printing technology is still in the early stages. But before long, it could be used to print anything from spare parts for appliances to human organs. Large printers already have been used to print an entire house. Manufacturers could use such printers to create parts for airplanes. And it is creations like this where security becomes an issue. A hacker who steals a wing design might be able to change it — and sabotage the plane, for example.

“We need to prevent these attacks,” Xu says.

This kind of printing is also known as additive manufacturing. Its use has been skyrocketing in recent years as costs for the hardware and printing “ink” have dropped.

An ordinary computer printer creates a flat version of a document by putting ink on paper. A 3-D printer works in a similar way. Most 3-D printed objects lay down one thin layer at a time. Its “ink” is what really distinguishes it. The printer’s nozzle deposits a thin layer of liquid plastic or metal, which solidifies or hardens as it cools. By building up layer after layer of the ink, the machine creates a solid, three-dimensional object.

To hack these printers, a spy needs to merely “listen” to the noise and energy the machine emits, including the magnetic fields that vary as it works. Both sound and electromagnetic energy travel as waves. By tapping into these waves, Xu says, a spy could identify the shape of what was being printed. This would allow someone to steal a design without ever seeing the original.

The human ear isn’t sensitive enough to do this. So Xu used a smartphone. Today’s average smartphone contains powerful microphones and other sensors. They can record the sound and changing magnetic fields produced as a 3-D printer works, Xu’s team showed.

The scientists used a two-step process to turn a smartphone into a spying device. First came the training phase. During this step, they used the phone to collect data as a printer printed. At the same time, they noted the up-and-down and side-to-side movements of the nozzle. By comparing the two sets of data, they could match changes in the sound or magnetic fields that reflected the movement of the nozzle. The scientists built these connections into a computer program.

Then came the testing. Using what they’d learned in the first step, the researchers had their computer program analyze data as something different was printed. A smartphone had recorded the sounds and magnetic fields during the process. The “trained” program successfully translated the new data into nozzle movements. And they revealed what had been printed.

Their inspiration

This type of data theft is known as a “side-channel attack.” It steals information by spying on a machine, rather than by swiping an object or hacking the computer program used to make it. Side-channel attacks in the new tests spied on a printer’s sounds and magnetic energy.

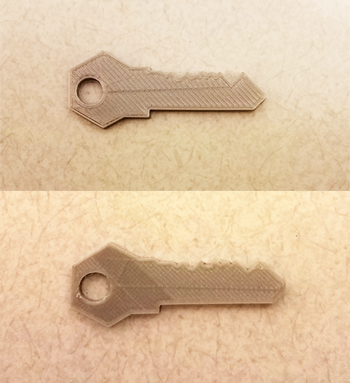

Xu’s group used data stolen from a working printer by their phone to copy an abstract but complex shape. It looked like a key. And the copy proved nearly identical to the original. Currently, this side-channel data can be used to print an object with 90 percent accuracy, Xu’s team showed.

Xu says this hack was inspired by the sounds he hears around him. People learn a lot by listening. “If we hear someone eating chips, we know they’re eating chips,” says Xu. “If someone is drinking water, we know they’re drinking.” So it goes with printing. His group suspected they could tell a lot about what a 3-D printer in the lab was printing, simply by listening to it. Then they set about testing that suspicion.

The group presented their results at a scientific conference in Vienna, Austria, on October 26.

Others have been concerned

Xu isn’t the first scientist to probe side-channel attacks on 3-D printers. Scientists at the University of California, Irvine, published an April 2016 analysis of acoustic (sound-based) side-channel attacks. Computer scientist Mohammad Al Faruque led those studies. His team has now identified several ways someone could eavesdrop on a 3-D printer, he says. Besides sound and magnetic fields, a spy could use data on heat or vibrations or power. The more sensors a spy uses, the more accurate their stolen data will be — and the more valuable the theft, Al Faruque points out.

Al Faruque says he’s glad researchers like Xu are expanding on his original work. “I’m happy that we discovered it and that people have started doing more research,” he says. “It is very important.”

Both Xu and Al Faruque say they’re now working on ways to beef up the security for 3-D printers. A printer might be shielded to avoid leakage, for example. Or extra noise might be added to the environment to confuse any listening “ear.” Ultimately, both researchers have the same goal.

“We don’t want to steal ideas,” says Xu. “We want to protect them.”

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.