In blazing heat, some plants open leaf pores — and risk death

Trying to keep cool in warming climates puts some plants at greater risk of drying out

Heat waves and droughts can have a roasting effect on vulnerable plants’ leaves. As the climate changes, blazing heat and lack of water may put some plants at greater risk.

Ben-Schonewille/iStock/Getty Images Plus

In sizzling heat waves, a new study finds, some parched plants especially feel the burn. Blazing heat widens tiny pores in their leaves, drying them faster. These plants could be most at risk as the climate changes.

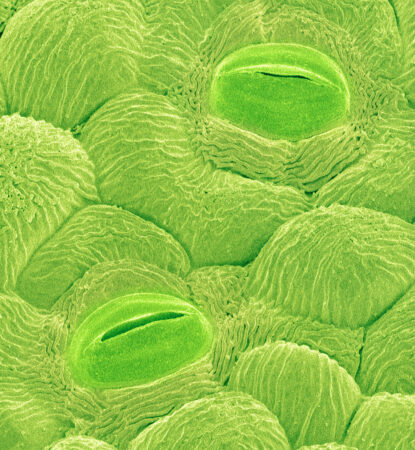

Stomata (Stow-MAH-tuh) are microscopic vents on plants’ stems and leaves. They look like tiny mouths that open and close with light and temperature changes. You can think of them as a plant’s way of breathing and cooling. When open, stomata take in carbon dioxide and exhale oxygen.

Open stomata also release water vapor. It’s their version of sweating. That helps the plant stay cool. But releasing too much water vapor can dry the plant. So in searing heat, stomata often shut to save water.

Or at least, that’s what many scientists think. “Everybody says stomata close. Plants don’t want to lose water. They close,” says Renée Marchin Prokopavicius. She is a plant biologist at Western Sydney University. That’s in Penrith, Australia.

But when heat waves and droughts collide, plants face a dilemma. With water scarce, soil dries to crumbles. Leaves bake to a crisp. What’s a scorching greenery to do? Hunker down and hold onto water? Or release vapor to try to cool its sweltering leaves?

In extreme heat, some stressed plants open their stomata up again, Marchin’s research now shows. It’s a desperate effort to cool down and save their leaves from roasting to death. But in the process, they lose water even faster.

“They shouldn’t be losing water because that will drive them really quickly towards death,” Marchin says. “But they do it anyway. That’s surprising and not commonly assumed.” She and her team describe their findings in the February 2022 issue of Global Change Biology.

A sweaty, scorching experiment

Marchin’s team wanted to find out how 20 Australian plant species handle heat waves and droughts. The scientists started with more than 200 seedlings grown in nurseries in the plants’ native ranges. They kept the plants in greenhouses. Half the plants got watered regularly. But to mimic a drought, scientists kept the other half thirsty for five weeks.

Next, the sweaty, sticky part of the work began. Marchin’s team boosted the temperature in the greenhouses, creating a heat wave. For six days, the plants roasted at 40º Celsius or more (104º Fahrenheit).

The well-watered plants coped with the heat wave, no matter the species. Most didn’t suffer much leaf damage. The plants tended to close their stomata and hold onto their water. None died.

But thirsty plants struggled more under the heat stress. They were more likely to end up with singed, crispy leaves. Six out of the 20 species lost more than 10 percent of their leaves.

In the brutal heat, three species widened their stomata, losing more water when they needed it most. Two of them — swamp banksia and crimson bottlebrush — opened their stomata six times wider than usual. Those species were especially at risk. Three of those plants died by the end of the experiment. Even the surviving swamp banksia on average lost more than four in every 10 of their leaves.

The future of greenery in a warming world

This study set up a “perfect storm” of drought and extreme heat, Marchin explains. Such conditions likely will be more common in the years ahead. That could put some plants at risk of losing their leaves and their lives.

David Breshears agrees. He is an ecologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson. “It’s a really exciting study,” he says, because heat waves will become more frequent and intense as the climate warms. Right now, he notes, “We don’t have a lot of studies that tell us what that will do to plants.”

Repeating the experiment elsewhere can help scientists figure out if other plants’ stomata will also respond this way. And if so, Breshears says, “we have more risk of those plants dying from heat waves.”

Marchin suspects other vulnerable plants are out there. Intense heat waves could threaten their survival. But Marchin’s research also taught her a surprising, hopeful lesson: Plants are survivors.

“When we first started,” Marchin recalls, “I was stressed out like, ‘Everything’s gonna die.’” Many green leaves did end up with burned, brown edges. But almost all of the crispy, thirsty plants lived through the experiment.

“It is actually really, really hard to kill plants,” Marchin finds. “Plants are really good at getting by most of the time.”