Help for a world drowning in microplastics

Researchers investigate plastic alternatives, special filters and new breakdown technologies

These bits are just some of the many tiny fibers, beads and shards of plastic that find their way into the environment — and its inhabitants, including us. Scientists think there must be a way to keep such pollutants from posing widespread risks.

pcess609/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Sharon Oosthoek and Maria Temming

Look around you. How many plastic items do you see? If you are like most people, there are probably a lot.

Research shows that people recycle only nine percent of plastic wastes. The rest — water bottles, pens, shopping bags — can end up in our water, air and soil. Exposed to light and waves, plastic breaks down into teeny-tiny bits. Known as microplastics, they have become a growing concern. That’s partly because when they end up in the environment, they also can end up in animals, our food and our drinking water.

The most recent estimate suggests that Americans alone eat or drink some 70,000 of these polluting microplastic bits each year.

Discarded plastic is not the only source of them. Some bits are made on purpose, for use in skin-care products and toothpaste. They’re used to scrub away dead skin and cavity-causing material on teeth. When we shower or rinse our mouths, those microplastics go down the drain. From there, they end up in our waterways.

Researchers have even shown that washing clothes made of fleece and other types of plastic sheds bits of lint. Those fibers also go down the drains and into the water.

Scientists began reporting microplastics in the ocean as far back as the 1970s. Since then, several hundred studies have shown that microplastics taint the environment. This includes the world’s oceans, lakes and rivers.

But research is underway to slow the growth of this pollution — and perhaps clean up some of what’s already out there.

The problem with plastics

Our drinking water comes from lakes, rivers and groundwater aquifers. Any of these may be tainted with microplastics. Our bodies can poop out plastics we’ve ingested, but no one knows how long it takes for them to move through the body, says Sam Athey. She studies sources of microplastics at the University of Toronto in Canada. The longer microplastics stay in our bodies, she says, the greater our exposure to them.

Researchers don’t yet know the risks, says Athey. But she finds reasons to be cautious. One is that plastic is made from oil and includes many different petroleum-based ingredients. Scientists don’t yet know how many of these might be toxic.

Ingredients in some plastics, such as polyvinyl chloride, can cause cancer. And phthalates (THAAL-aytes) — used to soften some types of plastics — can mimic the activity of hormones. These false hormones can cause unexpected changes in how cells grow and develop. Such changes may lead to disease.

Plastic also can soak up pollution like a sponge. The pesticide DDT and PCBs (a type of insulating fluid) are two types of toxic pollution found in plastics floating in the ocean.

Plastic bits also have been turning up in fish, birds, corals and other aquatic animals. That’s a problem because plastic does not provide the energy and nutrients these creatures need to grow and thrive.

The case for saying no to plastic

The simple solution is to not buy plastic items, says Peter Kershaw. He is an independent marine scientist who lives in Norwich, England. He wrote a 2018 report for the United Nations on alternatives that could help reduce plastic litter in the ocean.

“Ask yourself,” he says: “Do I really need that plastic bag to carry my shopping home?” Or do you really need a plastic straw to drink your soda or milk?

The leaders of some countries also have been asking that question. They’ve decided the answer is “no” and have banned single-use plastic items. These are things, such as packaging, that we use once and then throw away.

Bangladesh, Kenya and New Zealand are three countries that have banned plastic bags. Some U.S. cities and a few states also have banned them. Representing 28 countries, the European Parliament has agreed to ban nearly a dozen single-use plastics by 2021. Europe’s ban includes single-use cutlery, plates, straws and drink stirrers. Canada announced a plan to ban these, too, by 2021.

Such bans are a good start. But scientists say people must do more.

The promise and peril of biodegradable materials

One strategy is to find alternatives to conventional plastics. Some companies are starting to replace single-use plastic items with biodegradable alternatives. These new products are designed to break down into harmless chemicals.

Materials decay when microbes feed on them, breaking big molecules into smaller, simpler ones (such as carbon dioxide and water). Other living things can then feed on these breakdown products to grow.

Traditional plastic takes a very long time to decay. That’s because it’s made from petroleum, and few microbes choose to eat that. Biodegradable plastic, in contrast, is made from biological materials on which many microbes happily dine. These range from trees, sugarcane and corn stalks to shrimp shells.

But there is a problem with such materials, says Kershaw. They decay only at very high temperatures — typically 50º Celsius (122º Fahrenheit). Plus, those high temperatures must be maintained for several weeks for microbes to do their job.

Some cities have industrial compost systems that meet those conditions. But many do not. Instead, biodegradable plastic items can end up in a cold ocean or lake where they can take decades or even centuries to break down, depending on the type of plastic.

Sunlight can speed their breakdown. But scientists recently showed some biodegradable plastic bags were still strong and intact after three years outdoors. In that regard, they were not much better than regular plastic.

The other problem with biodegradable plastics is that people often toss them into the recycling bin with regular plastic.

“Once you mix them together — and they look the same, so people do it — it makes it harder to recycle the plastic,” says Kershaw.

Filtering microplastics from the laundry

Cleaning clothes has become an enormous source of waterborne plastic. Washing machines tumble and wear down fabrics. This releases lots of little pieces of lint. If the fabric was made from nylon, polyester, polyethylene or polyamide, for instance, those lint particles will be plastic.

One 2018 study found that polyester fleece was a big culprit. A study that came out two years earlier showed that washing a single 6 kilogram (13 pound) load of clothes made from synthetic fabrics could release some 700,000 plastic lint fibers into the wash water. That explains why some researchers are looking for ways to keep that lint from going down the drain.

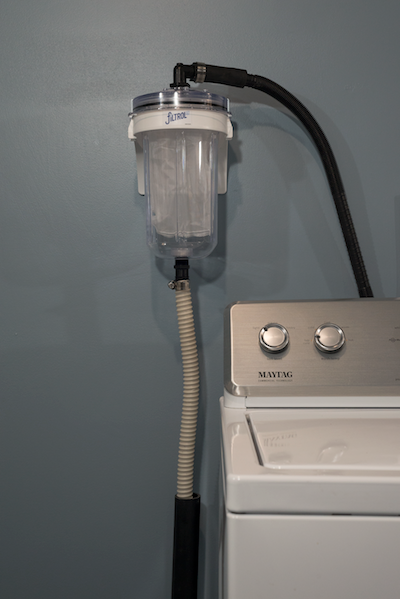

One project has been testing special filters to catch those fibers. It’s being run by researchers at the University of Toronto and at Georgian Bay Forever (a local environmental group). This past July, they installed the test filters on washing machines in 100 households in Parry Sound, Ontario. Parry Sound is on the shores of Canada’s Georgian Bay. It is part of Lake Huron.

The local water-treatment plants aren’t designed to remove microplastics. So any lint microplastics from the town’s wash will end up in the bay. The test filters are about twice the size of a standard water bottle. In recent tests, they removed roughly 90 percent of microfibers, notes project leader Lisa Erdle. She works at the University of Toronto.

“Testing in our lab shows they [the filters] work in a controlled setting,” she notes. “We’re curious to see if they work [just as well] in real people’s homes.” Whether they do may depend on whether people use the filters properly. For instance, she notes, “How often do they change the filter?”

Erdle and her team tested the wash water before the filters were installed. They are now repeating those tests to see how well the filters reduced the release of plastic lint.

The study will run for two years. Its results will be shared with the public. Because Parry Sound has a population of just 6,400, Erdle suspects the decrease in microplastic fibers will be noticeable.

The ideal solution would be to not manufacture plastic-based clothing in the first place, says Erdle. But filtering lint out of wash water and then burying it in a landfill would at least keep the pollution out of our waters.

Can nanotechnology bring mega benefits?

What about the microplastic pollution already polluting rivers, lakes and the ocean? In July 2019, researchers in Australia reported a potential solution for breaking microplastics into smaller, harmless molecules.

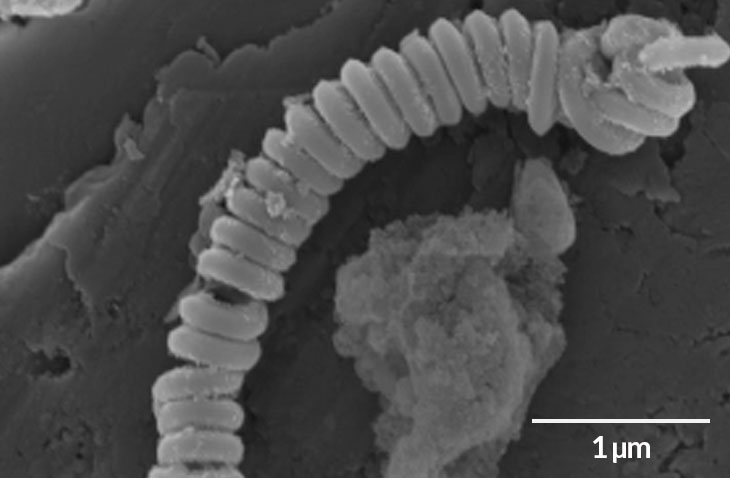

They created nanometer-scale coil-shaped tubes. Made from carbon, these tubes are too small to see (even with a classroom microscope). But they may produce a very visible change in water pollution by breaking down microplastics.

Here’s how they work: The carbon nanotubes are coated in nitrogen. When mixed with a compound known as POMS (short for peroxymonosulfate [Per-OX-ee-mon-oh-SUL-fate]), the nanotubes create new chemicals. Known as reactive oxygen species, or ROS, these new chemicals crumble microplastics into smaller components.

Chemical engineer Jian Kang led the research. He works at Curtin University in Perth. His team added their carbon nanotubes to 80 milliliters (one-third cup) of water tainted with microplastic particles. Then they warmed the water to 120 °C (248 °F) for eight hours. Heating the water speeds the process. Manganese embedded within each nanotube made the tubes magnetic. This meant the researchers could use magnets to pull them out of the water for reuse.

The treatment reduced the amount of microplastics in the water by about a third to one-half, Kang’s group showed. It reported the findings on July 31, 2019 in the journal Matter.

Chemicals produced by the plastic’s breakdown don’t appear very toxic, notes Long Chen. He is an environmental engineer at Northeastern University in Boston, Mass. Chen was not involved in the work. The Australian researchers exposed green algae to water containing the microplastic by-products. After two weeks, they saw no change in the algae’s growth.

Clearly, more research is needed. But the early testing does appear promising.

“It’s great to have this option as a tool in a toolbox” to curb microplastic pollution, says Bart Koelmans. He is an environmental scientist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

However, researchers caution there still is a lot of work to do. What’s more, Koelmans says, such new programs to clean up plastics “should not dismiss us from thinking about what the real problem is — and that’s the [release] of plastic into places where it does not belong.”

Correction: This story initially reported that people can excrete microplastics in urine. There are no data that yet support that. Data do show, however (and as cited above), that they can be excreted in feces.