Helping to save elephants

Preserving an enormous creature like the Asian elephant can be very challenging.

By Emily Sohn

I wouldn’t last a minute in the circus.

At a recent exhibit at the Science Museum of Minnesota in St. Paul, I had a chance to try. I stuffed my body into a contortionist’s box and almost got stuck. I attempted to walk across a tightrope hanging low to the ground, but I wobbled and fell off after nearly every step. I couldn’t even lift the big, heavy stick that acrobats use for balance.

When I left the museum, I was more convinced than ever that the best place for me at a circus is in the audience.

If I were an Asian elephant, however, I might consider joining the circus. That’s not because the bulky animals have it any easier than the rest of the troupe. In fact, circus elephants train for hours every day to learn their routines. Yet, for endangered Asian elephants, a circus might be a safer place to live than any wild area in Asia.

|

|

Asian elephants, young and old, at the Center for Elephant Conservation in Florida.

|

| Feld Entertainment/Center for Elephant Conservation |

The Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey® circus, in particular, has been working extra hard in recent years to help keep Asian elephants from dying out. At its Center for Elephant Conservation in central Florida, scientists and trainers focus entirely on protecting, breeding, and studying Asian elephants.

“Regardless of what happens in Asia, it’s our goal to ensure that the Asian elephant doesn’t disappear from the earth,” says animal behaviorist John Kirtland, executive director of animal stewardship at Feld Entertainment, the company that produces the Ringling Bros. circus. “We want to preserve it for our children and our children’s children.”

First impressions

With elephants, first impressions can be quite impressive. After spending about 22 months inside their mothers’ wombs, baby Asian elephants are born weighing an average of 250 pounds. Adult females weigh between 8,000 and 10,000 pounds. Fully-grown males can weigh as much as 12,000 pounds. Adults can grow to be 10 feet tall. Males have huge, beautiful ivory tusks.

Preserving such an enormous creature can be an enormous challenge. There are two species of elephants living on Earth today. The species that lives in Africa is threatened, and Asian elephants are in big trouble.

One fifth of the world’s people live in Asia, and their activities are squeezing elephants out. Meanwhile, poachers are killing males at an alarming rate for their tusks, which sell for lots of money on the black market.

Today, there are probably fewer than 35,000 elephants living in the wild in Asia, Kirtland says. That may sound like a big number, but the future looks bleak. For one thing, elephant populations have been split up into small, vulnerable groups. Also, with so few males left, it’s hard for elephants to mate efficiently.

In fact, Asian elephants are so threatened now that Kirtland estimates they could disappear in fewer than 20 years. “The Asian elephant is going to go extinct as a wild animal,” he says, “because the wild does not exist anymore.”

|

|

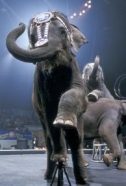

Asian elephants performing at the circus.

|

| Feld Entertainment/Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus® |

Still, Kirtland and his colleagues at Ringling Bros. want to make sure that the animals don’t disappear altogether, even if they remain only in captivity. Ringling Bros. itself has 55 Asian elephants in its herd. At any given time, about half of them are on tour with the circus. The rest hang out at the Center for Elephant Conservation (CEC), where they train, participate in studies, or relax, depending on their stage in life. Ringling Bros. finished building the facility in 1995 on a 200-acre site between Tampa and Orlando.

Mating in captivity

Altogether, fewer than 100 elephants have been born and bred in the United States in the 200 years since Asian elephants were first brought to the country. Since the early 1990s, Ringling Bros. has bred 16 of the 42 Asian elephants born in North America, equal to the number produced by all the zoos combined.

One of the biggest challenges of maintaining a thriving elephant community is getting the animals to mate in captivity. With practice, scientists have learned some important tricks. “You don’t just put a male and female together,” says Kirtland.

After working with animals for years, Kirtland believes that a healthy dose of competition is the key for successful courtship. “If you put one guy in a room full of women, he’s casual,” he says. “Put several guys in a room full of women, they have to compete for the women’s attention.”

One project is trying to skirt the courtship issue altogether by looking at the possibility of artificial insemination. Researchers are trying lab techniques to fertilize female elephants without mating them. CEC veterinarians also draw blood regularly to see which elephants are pregnant or ready to mate.

By keeping animals in captivity, scientists have had a chance to learn basic things about elephants that wouldn’t be possible otherwise. Trained elephants will stand still during uncomfortable medical procedures, for example, allowing researchers to collect general information about their bodies and health.

As part of another, more conservation-minded project, researchers at the Center are studying how elephants perceive smells. They want to find odors that are particularly repulsive to elephants so that they can design “odor fences” that would keep wild elephants from destroying farmers’ crops. That might win the animals additional human friends in Asia.

Future generations

Despite all the research and conservation efforts at the Center, there are still plenty of animal lovers who hate zoos and circuses. They argue that it’s not fair to keep exotic animals locked up in artificial environments. Some local governments have even banned animal acts in their towns, fearing that the animals aren’t treated well.

|

|

Asian elephants enjoying a cooling shower.

|

| Feld Entertainment/Center for Elephant Conservation |

Kirtland disagrees with such criticisms. For one thing, circus elephants live longer than zoo elephants or elephants in the wild, he says. In captivity, they can live well into their 60s and 70s. In the wild, a female elephant is lucky to reach 50. Males rarely live longer than 30 years.

The circus has the potential to benefit future generations of elephants, too, Kirtland says. In almost every city the company visits, Ringling Bros. holds an animal open house where ticket-holders can visit the animal compound, talk to the staff, and learn about the animals.

This kind of personal connection can make all the difference, says Kirtland, who saw his first elephant in a circus when he was 5 or 6 years old. “For many people, the first or only time they ever see an elephant is when the circus comes to town,” he says.

Most people will never get to Africa or Asia on extended safaris. Yet each year, more than 200 million people go to circuses and zoos, Kirtland estimates. Ringling Bros. alone visits within 90 miles of more than 90 percent of the U.S. population. Once people have seen exotic animals, researchers hope, they will be more likely to want to help protect them.

Working with humans

Elephants have a long history of relationships with humans. For thousands of years, people have been using the animals to help with agriculture, logging, and military activities. Elephants have also taken on important roles in mythology and religion. Ancient religions in India, South China, Sri Lanka, and elsewhere have featured gods that had elephant heads.

There’s plenty to admire. Elephant cultures are complex, and the animals are surprisingly smart. They can learn to respond to more than 60 vocal commands. And they seem to form friendships with their trainers.

At least, the trainers seem to think so. “Our elephants are part of our family as much as our human partners are,” Kirtland says. “We’ve all missed holidays, family gatherings, and birthdays because the needs of our animals come first.”

Elephant-like animals have lived on earth for more than 55 million years, far longer than we have. It’s perhaps this sense of majesty that drives Kirkland and many of his colleagues to work so hard at saving them. “They are magnificent animals,” Kirtland says. “A world without elephants would be a much sadder place.”