Here’s how butterfly wings keep cool in the sun

They have living structures that release more heat than nearby dead scales

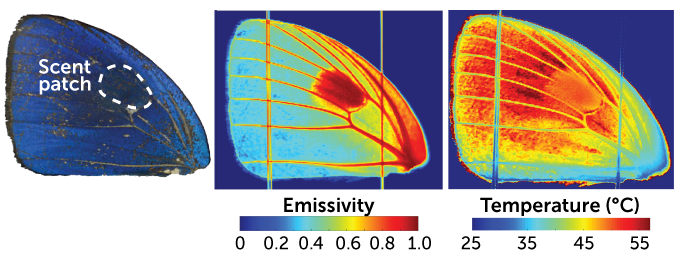

Butterfly wings have living parts — veins that pump insect blood and scent patches that emit smelly chemicals. Those veins and scent patches also help them release more heat than surrounding dead scales. Brighter areas in these infrared images correspond to higher heat release.

Nanfang Yu and Cheng-Chia Tsai

Butterfly wings are pretty cool, literally. That’s due to special structures that protect them from overheating in the sun.

Researchers took new thermal images of butterfly wings. These images showed the heat released by each part of a wing, which revealed the living parts of the wing. Those parts include veins that transport insect blood. Those veins also release more heat than surrounding dead scales. And that keeps the living wing parts cooler than the dead ones. The researchers described their findings January 28 in Nature Communications.

Tracking the insect’s heat is important. Small changes in body temperature can affect a butterfly’s ability to fly. The muscles in the insect’s midsection — its thorax — must be warm. That’s so the butterfly can flap its wings fast enough for takeoff. But the butterfly’s wings are thin. So they heat up faster than the thorax and can rapidly overheat.

People might think that butterfly wings are lifeless. They may think they are like a fingernail, a bird feather or a human hair, says Nanfang Yu. He is a physicist at Columbia University in New York City. In fact, he notes, those wings contain living tissues. These tissues are crucial for survival and flight. High temperatures will make the insect “really feel uncomfortable,” Yu says.

What’s in a wing

Butterfly wings are almost see-through thin. And that makes it difficult for heat-sensing cameras, called thermal infrared cameras, to distinguish whether the heat they “see” comes from the wing or from background sources. Yu and colleagues were lucky though. They found a technique that allowed them to measure the wing temperature. They studied the wings of more than 50 butterfly species. This allowed them to measure how much heat was emitted from specific wing parts.

The wings had distinct features that helped them stay cool, the researchers found. The first was a thick substance called chitin (KY-tin) that covers veins in the wings. Insect blood called hemolymph flows through those veins. The chitin is thicker over the veins. And it releases excess heat. Chitin also is what gives the rest of the butterfly it’s tough exterior.

There’s another wing part does that too. It’s a tiny structure shaped like a tube. On the scale of a billionth of a meter, it’s called a nanotube. A butterfly’s wing can have several of them. These sit on wing structures known as scent pads. These pads give off certain smells that males can use to attract mates. Scent pads contain both the nanotubes and chitin. The chitin makes the veins and scent pads thicker than dead material, such as the scales covering each wing. The tubes give the scent pads a hollow structure. Thicker or hollow materials are better at radiating heat than thin, solid materials, Yu says.

A butterfly can still overheat. That’s why it will move away from intense light if it gets too warm. But the chitin and nanostructures protect a wing only up to a point. To test this, the researchers beamed a laser on the wing’s scales. Their temperature rose, Yu says — “but butterflies can’t feel it and they don’t care.” When the laser’s light warmed a butterfly’s veins too much, the insect flapped its wings. Or it moved away from the heat.

The team also discovered some butterflies have what looks like a beating “heart” on their wings. This structure pumps insect blood through the scent pads. And it “beats” a few dozen times per minute. The team found it in two species of butterflies, the males of the hickory hairstreak (Satyrium caryaevorus) and white M hairstreak (Parrhasius m-album).

It’s surprising to find such a structure in the middle of the wing, Yu says. Why? To fly well, he explains, the wing has to be light. The extra structure adds weight. Still, that it exists, he says, “can only mean that this wing heart is very important for [the] function and health of the scent pad.”