Under the ice, a hidden lake hints at its origin — and coming end

Lake Mercer may serve as a model for understanding other subglacial Antarctic lakes

Lake Mercer is hidden beneath 1,100 meters of ice in Antarctica. In 2019, scientists traveled to the area to drill into its lakebed. The researchers slept in these small tents.

Billy Collins, SALSA project

By Douglas Fox

Antarctica is a land of hidden lakes. More than 600 have been mapped beneath the continent’s ice sheets. An estimated 140 are “active.” That means they’re constantly filling, then draining their water through rivers that flow beneath glaciers. But it’s been hard to learn how and why these lakes form — or how long they’ll last. New clues dug from the floor of one of them, Lake Mercer, now suggest some answers.

This subglacial lake sits roughly 300 kilometers (almost 190 miles) south of the Kamb ice cavern. Lake Mercer is a bit odd, at least in comparison to surface lakes. It sits on the side of a hill. Only the pressure of the vast ice atop it holds its water in place.

But this lake won’t always be there, predicts Ryan Venturelli. She’s a glacial geologist with the Colorado School of Mines in Golden. She’s part of a team that has been examining sediment pulled up from the lake’s floor.

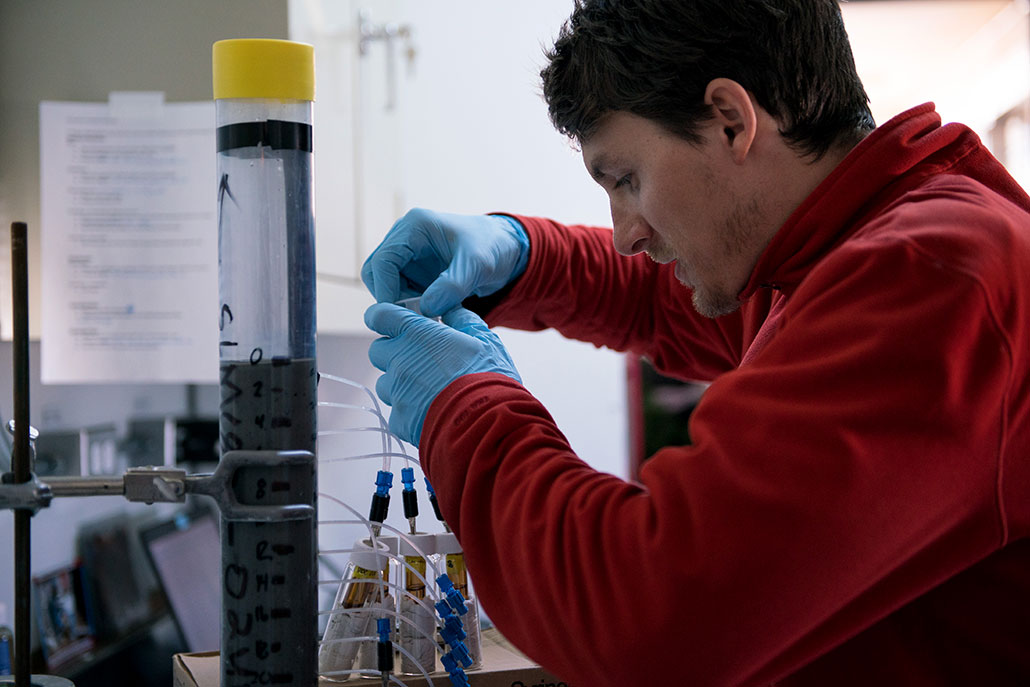

In 2019, scientists drilled through 1,100 meters (seven-tenths of a mile) of ice to collect mud cores from its lakebed. Her group has compared those sediments to satellite data of the glacier atop the lake. Since about 2003, such satellite data have shown signs of floods coursing under the glacier.

From these data, Venturelli now estimates Lake Mercer is about 180 years old. But its years appear to be numbered. The glacier above it thickening. At some point, she says, the sheer weight of all that ice will squash the lake out of existence, sending its water elsewhere. “We predict that this will be in 20 to 70 years,” she says.

In the March 9 Geology, her team reports how it arrived at that date.

What lake-floor rocks have to say

Matthew Siegfried is another glaciologist at the Colorado School of Mines. He and Venturelli identified patterns in the cores of lake sediment. They found seven pairs of chunky and fine layers. Those layers resemble ones recently seen at the Kamb ice cavern.

Venturelli and Siegfried now believe that the layers in Lake Mercer’s floor mark a series of floods. Each deluge started somewhere upstream. After spurting over the top of a hill, this water gushed into — and filled up — Lake Mercer. But this fast-moving flood water came to a standstill in the lake. There, it dropped chunky sediments it had been carrying. This is how each of the chunky layers formed. During the years between floods, water flowed into the lake more slowly. Slow water could only carry tiny particles of sediment. It left these tiny grains on the lake floor, creating the fine layers.

Those layers suggest the story of the lake’s birth, says Venturelli. Mercer likely formed when the glacier above it started to slow and thicken. This increased the pressure at the glacier’s base, which sped up the melting of ice on its underside.

That meltwater accumulated to form the lake on the downstream side of the hill. But calculations by Siegfried and Venturelli suggest this lake is not permanent. The crushing weight of the overlying ice will kill it — and maybe soon.

In a few decades, the glacier above Lake Mercer will become thick enough that it will squish the lake out of existence, predicts Venturelli. Its pooled water will then flow to a new location — perhaps forming a new lake.

This subglacial world is shaped by different forces than the surface world. Down here, changes occur quickly as glaciers speed or slow, causing their ice to thin or thicken. Satellites show that the ice sheets throb up and down as flood waters beneath them pulse through. As water pools and bursts free, lakes form — and then disappear. Rivers change course.

This all happens out of sight. But thanks to scientists’ persistent efforts, these processes are now less of a mystery.