HIV: Reversing a death sentence

Amid gains in treating and preventing HIV, scientists are angling for a cure

Duzi Howerton plays soccer, dances hip-hop — and was born with HIV. His family chose to share his diagnosis earlier this year. They hope to show people that given the right drugs, HIV-positive kids can live relatively normal, long lives.

Courtesy of Jodie Howerton

By Bryn Nelson

In 2010, a U.S. family — the Howertons — adopted 5-year-old Duzi from South Africa. At 8, the boy now dances hip-hop and plays so many sports that his mom, Jodie, can hardly keep track. In nearly every way, he is a normal, active third-grader.

Earlier this year, however, the Howertons decided to share a secret. Duzi (DEW zee) had been born with HIV. It’s the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome, better known as AIDS.

A few years ago, German doctors stunned the world by revealing a different secret. They announced that one of their patients appeared to be the first person ever cured of HIV (which stands for human immunodeficiency virus).

The virus had no name when it burst onto the medical scene, in 1981. Doctors wondered where the mysterious new infection got its start. But one thing quickly became clear: Its victims tended to die within a few years of becoming infected.

Brown may have beaten the odds, but HIV remains a very dangerous virus. More than 2 million new cases emerge around the world each year. Globally, an estimated 35 million people have already died from AIDS. That’s more than the entire population of Pennsylvania and New York combined.

Not long ago, an HIV diagnosis was considered a death sentence. No longer. People now can live with HIV for decades. By taking the right drugs, kids like Duzi are showing that people with HIV can live relatively normal, long and productive lives. And people like Brown are offering researchers hope that a time may come when no one will have to live with the virus at all.

“I think the possibility of finding a cure or a vaccine for HIV is something that we all hope for. And we have very good reasons to have hope right now,” says Annette Sohn. She’s a doctor who treats HIV-positive kids in Bangkok, Thailand.

Myth busters

Many scientists are excited by recent progress in treating people with the virus and preventing its spread. Others are getting closer to understanding its true origins. By contrast, researchers say public knowledge of the disease is often out of date. Still, many myths prevail.

Even today, some people believe they can pick up an HIV infection just by touching someone with the virus. “That is simply not true,” says Roy Gulick. And he should know. Gulick heads the division of infectious diseases at Weill Medical College, part of Cornell University in New York City. People can’t pass on the virus by shaking hands, hugging, kissing or sharing silverware, he notes. The virus spreads mainly through sexual contact or exposure to the blood of an infected person.Myths can also frighten the families of infected people, notes Theodore Ruel. He’s an infectious-disease doctor at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital. (UCSF stands for the University of California, San Francisco.) Ruel recalls one young man who recently learned he had HIV. “His mother was beside herself with terror about this because she was afraid that she was going to get it from him,” Ruel says. He had to reassure her: “You do not get HIV from casual contact, even when you’re living in the same house.”

|

That stubborn myth is one reason the Howerton family decided it was time to finally tell everyone about Duzi’s HIV. Medicines have his disease under complete control, Jodie says, and he poses no danger to anyone. She hopes that message will reduce some of the remaining fear of people infected with HIV.

“If he had any other illness that required management and medication, there would be no stigma attached to it and no fear of telling others,” she says. “We decided to teach him right from the beginning that there’s nothing to be ashamed of and nothing to hide.”

Duzi’s birth mother likely passed the virus on to him when he was born. That type of mother-to-child spread of HIV can be largely prevented now. Still, many pregnant women in poor countries can’t afford the life-saving drugs that would improve their health and keep their babies from becoming infected. “That is a major injustice in our world: that there’s not enough access to this medication,” Jodie says.

Expanding treatment

Nonprofit groups around the world are working hard to overcome that obstacle, says Sohn. She directs the TREAT Asia program, which stands for Therapeutics Research, Education, and

This hard work to get more people treated has led to a “dramatic” drop in deaths from AIDS and in new HIV infections, says a new report. It was released in September by a United Nations group called UNAIDS.

By 2015, the group hopes treatment will reach a total of 15 million HIV-infected people worldwide. “That’s a really big goal,” Sohn admits. “Not only is giving people treatment beneficial for them as individuals, but it also helps to prevent new infections in the community.”

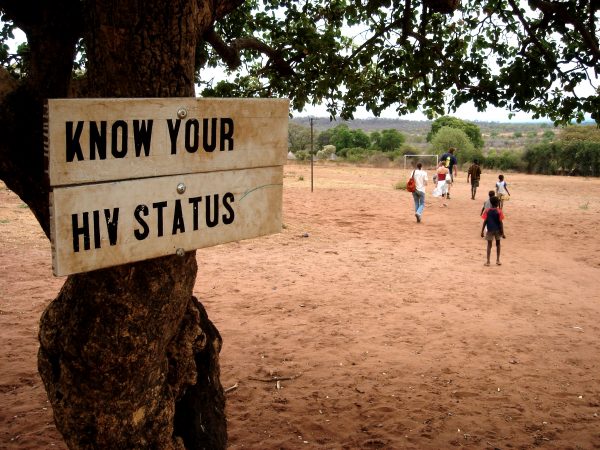

Most people who know they have HIV are careful so that they don’t risk spreading the virus, Gulick says. That’s why it is so important that people learn whether they are infected — and that they seek treatment if they are. Doctors also found that anti-HIV drugs reduce the risk of passing on the disease by 96 percent. “So one of the most effective ways we can prevent HIV is actually to treat people with the disease,” explains Gulick.

|

That’s especially true for pregnant women infected with HIV. Medicines can help ensure that, on average, fewer than two babies out of every 100 born to an infected mother will pick up her infection. “That is something that we consider a great success,” Sohn says. “As long as we can give the mom and her baby the right medicines, we can protect the future of these children.”

UNAIDS reported in its 2013 global report that giving more infected mothers anti-HIV drugs is paying off in a big way. From 2009 to 2012, the group estimates, better access to medicine prevented more than 670,000 children from becoming infected.

Although that effort was too late for Duzi, the drugs he’s taking now are helping to topple the myth that all people with HIV will die from AIDS. In fact, people who are treated with HIV drugs have life spans that are close to that of most people, says Gulick. “That means you can live your whole life with an HIV infection if you take your medications.”

So far, scientists have developed nearly 30 drugs to fight HIV. Within just the past five years, these drugs have improved so much that many patients can control their infection by taking only one pill a day (with three types of medicine inside).

A formidable foe

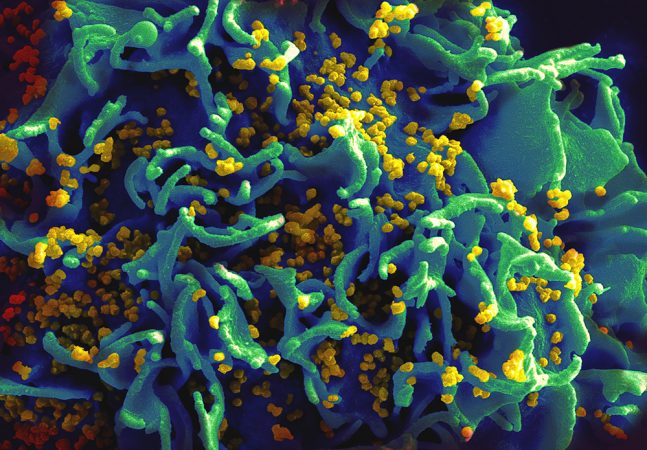

Attempting to cure HIV is proving much harder. Like most viruses, HIV is a tiny invader. About one-sixtieth the size of a human cell, the virus makes up for its petite size by hijacking the machinery within our cells to make copies of itself.

Once inside a T cell, HIV inserts its genetic blueprint into the cell’s DNA. That’s like hiding its own assembly plans within our body’s instruction manual. “To truly cure yourself of HIV, you would have to purge all of the cells that were infected by it from your body,” explains Ruel.

And that’s easier said than done.

HIV can take advantage of the cell’s machinery and force it to become a virus factory that can crank out 10,000 copies or more. The viral copies that push their way out of the hijacked factories can then attack many other cells. In the process, HIV can gradually destroy the body’s immune system.

Someone infected with HIV will develop AIDS once most of the immune system’s T cells have died. But the infection may not be noticed until that person picks up a second infection — one that preys on people with a weakened immune system. Although most people could easily fight off these new infections, those with AIDS cannot.

|

Fortunately, drugs can kill off most of the virus. But researchers recently discovered that far more infected cells than previously thought can remain tucked away in places where they’re hard to find. In these “hidden pools,” the infected cells essentially fall asleep. And that means they don’t produce any new copies of the virus. “So it’s hard to detect those cells and you don’t know which ones have the HIV infection inside,” Gulick says. “At any moment, one could be activated to start producing virus again.”

That can happen whenever a patient stops taking drugs. Suddenly, these cells can wake up and begin churning out more HIV copies. Even worse, these copies can evolve over time. That means they tend to acquire new mutations, some of which may make them much harder to destroy.

Now that researchers know how the virus can hide out, they have begun figuring out ways to wake sleeping T cells. This method will let them identify which are infected and then target them for removal. Ruel compares the strategy to coaxing a forest full of bears to come out of hibernation — but only once well-armed hunters can spot and take out the rabid ones.

Closer to a cure?

Given the huge challenges, many researchers once gave up on curing HIV, Ruel says. A few remarkable patients, however, have changed researchers’ minds. “Within the last five years, a couple of special cases have entirely renewed hope for a cure,” Ruel says. One of them is Timothy Brown. Sometimes called “the Berlin patient,” doctors think he may be the first person who ever defeated the virus.

After tests showed Brown had HIV, he took drugs to control the infection. Eleven years later he received more troubling news: He had developed a dangerous type of blood cancer. To save his life, doctors in Germany tried a radical treatment. They killed off his entire immune system using powerful drugs and radiation (an intense beam of energy that kills targeted cells). Then they gave him a new immune system assembled from cells donated by a healthy volunteer. Doctors refer to this procedure as a stem cell transplant. The implanted stem cells can develop into the wide variety of very specialized cells that make up the immune system.

But Brown’s cancer returned. So doctors transplanted a second batch of stem cells from the same donor.

In the end, the complex procedure cured his cancer. And when doctors tested Brown for HIV, they found that the virus was gone as well. So some part of his cancer treatment likely cured his HIV infection. What’s more, his once-depleted T-cell strike force also recovered and reached full strength.This amazed Brown’s doctors. “They’ve followed him for over six years after all of this, and he appears to be the first person ever cured of HIV,” Gulick says. “One of the mysteries though, is that we don’t know exactly what did it.”

Brown’s doctors may have provided an important clue, however. When searching for the perfect donor to help rebuild Brown’s immune system, they picked a man with a rare genetic mutation. It’s one that makes people especially resistant to acquiring an HIV infection.

Here’s how it works: The entryway through which HIV barges into T cells is like one door with two doorknobs. To get inside the cell, the virus must grab and turn both knobs. In fewer than one out of every 100 people, however, a slight change in one gene essentially makes the second doorknob disappear. And this protects them from HIV by making it much harder for the virus to get inside their T cells. The donor passed along those altered cells to Brown. Those cells reproduced within Brown’s body, denying HIV access to the new T cells.

Joining the fight

|

Researchers say it wouldn’t be practical or ethical to try the same strategy on others. “My cure was very expensive and very dangerous. I almost died several times,” Brown tells Science News for Students. But his experience does show a cure is possible. And with that knowledge, researchers are trying out new strategies on other patients.

One approach works like this: Doctors take uninfected T cells from HIV patients and knock off one of the two doorknobs used by HIV. They then return the altered cells to the patients. Scientists are testing whether this method blocks the virus from entering those modified cells.

Researchers are also studying how an HIV-positive baby in Mississippi may have beaten the virus. Doctors knew that the girl was infected from birth. So they gave her a strong dose of anti-HIV medicine right away. Scientists now believe the treatment snuffed out the virus before it could spread throughout her body. “It’s like a match got thrown on the woodchip pile, and you extinguished the match before it could set the rest on fire,” Ruel says. A recent study confirms that the girl – now 3 years old – remains HIV-free, even though she hasn’t taken any anti-HIV medicine for 18 months. The potential cure means that doctors could try a similar strategy with other infected babies.

Meanwhile, research is starting to make a big difference in survival for people infected with HIV. “People are doing so well that you don’t read about HIV and AIDS on the front page of the [news]paper,” Gulick says, or at least it’s no longer the top news story. But he and other researchers say the exciting success is contributing to a new and troubling myth — that HIV is no longer a problem.

Despite advances in the fight against this disease, experts stress that HIV still infects roughly 50,000 new people every year in the United States. Many of these people are younger than 25, Gulick observes. And not all take the medicine they need to stay alive and help prevent the spread of the virus. “So the HIV epidemic certainly is not over,” he notes. And that’s just the United States, where the treatments are relatively easy to get.

Researchers and activists are determined to make more headway in their battle against the virus, however. In 2012, Brown launched the nonprofit Timothy Ray Brown Foundation of the World AIDS Institute. The Washington, D.C.-based organization is entirely focused on finding a cure, he says. “I really want everyone in the world who has HIV to be cured of it,” says Brown, now 47. “I believe it’s going to happen in my lifetime.”

A self-employed writer, Jodie Howerton is raising money for educational videos. Her goal: to update what kids are taught about HIV in public schools. She’s troubled at the recent uptick in infections among teens and young adults. “People are getting newly infected because I think we’ve fallen down on the job of education,” she says. Just as importantly, though, she’d like to help teach others about how to interact with people infected by HIV, like her son.“There’s really nothing to fear from people who have the disease,” she says.

Power Words

AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) A disease that weakens a body’s immune system, greatly lowering resistance to infections and some cancers.

DNA (short for deoxyribonucleic acid) A long, spiral-shaped molecule inside most living cells that carries genetic instructions. In all living things, from plants and animals to microbes, these instructions tell cells which molecules to make.

epidemic A widespread outbreak of an infectious disease that sickens many people in a community at the same time.

gene A segment of DNA that contains the instructions for making a protein. Those proteins govern the behavior of a cell — or large groups of cells. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) A potentially deadly virus that attacks cells in the body’s immune system and causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome, or AIDS.

HIV-positive (or –negative) A designation given to people whose tested blood shows they have become infected with HIV (or not infected, if they are HIV-negative).

immunity The state of being immune to, or having resistance to, a particular infectious germ.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body fight off infection.

infection The successful invasion of adisease-causing microorganism into the body, where it multiples, possibly causing serious injury to tissues (such as the skin, lungs, gut or brain).

infectious A germ or other pathogen that can be transmitted to people and other organisms through the environment.

mutation Some change that occurs to a gene in an organism’s DNA. Some mutations occur naturally. Others can be triggered by outside factors, such as pollution, radiation, medicines or something in the diet.

radiation Energy that is carried by waves through space. Heat, light, electricity and streams of radioactive particles are all forms of radiation.

stem cells Cells that don’t yet have a distinct identity but can mature into many different cell types in the blood, skin, brain and other parts of the body.

stigma A negative belief or assumption that people often associate with a particular person, trait or occurrence.

T cells A family of white blood cells, also known as lymphocytes, that are primary actors in the immune system. They fight disease and can help the body deal with harmful substances.

vaccine A biological mixture that resembles a disease-causing agent, given to help create immunity to a particular disease.

virus A tiny molecule made of a protein shell that encloses genetic information. A virus can live and multiply only in the living cells of a host organism, such as people.